August 23, 2022 |

November 1, 2022

In British Columbia, Canada, an innovative wildfire mitigation program uses cows to forage in forests to reduce the intensity of fire.

“Cattle are already on these landscapes, and we’re just using their grazing pressure in a different way,” said Amanda Miller, an ecologist at Palouse Rangeland Consulting, who was contracted to conduct the fieldwork for the program. “They’re bulk grazers—better suited than goats or sheep to eat grass-dominated fine fuels that burn—and they don’t need protection from predators in the same way, because a coyote can’t take down a 1,200-pound cow.”

The program started out as a pilot project, with geographic information system (GIS) technology used to stratify landscapes and analyze the best test plots and monitor grazing effectiveness. It’s been deemed a success and will continue, because it’s good for the forest and the cows.

Wildfires have always been part of the natural landscape of British Columbia. Occasional summer burns have long kept the scenic vistas of towering forests and stretches of grasslands in balance, removing dead ground cover and protecting trees from more intense fires that threaten the delicate ecosystem. In recent times, climate change and human management have altered this balance, causing larger and more frequent wildfires with significant consequences.

“The intensity of wildfires in the province has been increasing over the past 10 years,” said Shawna LaRade, the range officer with the Government of British Columbia who oversees the program. “We know the fires are not going away, and climate change is going to continue to influence the potential for catastrophic fires.”

Targeted grazing has been shown by the researchers to manage fire threat with minimal impact on the ecosystem. The grazing program is sponsored by the British Columbia Cattlemen’s Association, after seeing how grazing changed fire behavior and acted to create “agricultural firebreaks” during the province’s devastating 2017 and 2018 fires. Participating ranchers are focusing the grazing effort on plants adjacent to communities in rural/urban interface areas where summer-dried grasses accumulate and the potential for wildfire to threaten homes and communities is high. Grazing reduces fine fuels and promotes the growth of new, green grasses, which maintain moisture and burn more slowly. The newer growth is also shorter, and therefore less likely to spread flames to taller brush and trees.

Community response to the project has been supportive, with cooperation from forestry staff, First Nations partners, and city officials. “The City of Kelowna is a very engaged partner on one of our projects, and then also just the community members themselves,” Miller said. “The local fire departments are super supportive of anything that can reduce the potential of structural fires.”

The project, launched in 2019 with funding provided through the Canadian Agricultural Partners, the BC Ministry of Forests, and BC Wildfire Service, was inspired by the disastrous 2017 and 2018 wildfire seasons, which together burned over 1,000 square miles of grasslands and forests. The goal was to discover whether targeted grazing could be used to mitigate the risk posed by wildfires to residents and local communities.

“Unfortunately, the grasses within the East Kootenay can quickly overgrow an area,” said Mike Morrow, wildfire prevention officer for the SouthEast Fire Center. “While long and lush, the grass acts as a barrier, however, once that grass dries out it can contribute to fire intensity and cause a significant increase in rates of wildfire spread.”

In many of British Columbia’s grasslands, wildfires are part of the natural cycle. The project seeks not to eliminate wildfires but to contain them and prevent the kind of catastrophic blazes that ignited over 3,000 square miles of land in British Columbia during the 2021 season.

Particularly dangerous are crown fires, which burn hotter and faster between treetops, making them impossible to control and fight. “We feel the threat to Cranbrook is significantly reduced,” Morrow said. “By utilizing cattle within specific areas adjacent to the private lands, if a fire were to start south of town and burn north, the fuel reduction treatment should lessen the intensity and help slow it down. Intensive grazing, coupled with landowners own FireSmart activities, should help prevent fire damage.”

Targeted grazing partially mimics the way British Columbia’s grasslands have historically been kept under control, and herds of elk continue to roam and graze many of the project areas in the East Kootenays. Cattle are the most effective and efficient choice today, being both plentiful and easy to manage. Additionally, grazing highlights the contribution that the agricultural industry can make to its communities with local cattle. “We’re using existing resources; it’s still part of the local food chain,” Miller said. “I think it’s positive all around, because it illustrates that we can support a locally sourced foodstuff while enhancing community protection values.”

The allocation of forage to livestock is carefully managed to maintain healthy ecosystems, habitats, and a forage base for wildlife. “We have a significant wildlife population at the landscape level that we’re managing, so a safe and allocated use for cattle grazing is an important part of resource management and sustainable, healthy ecosystems,” LaRade said.

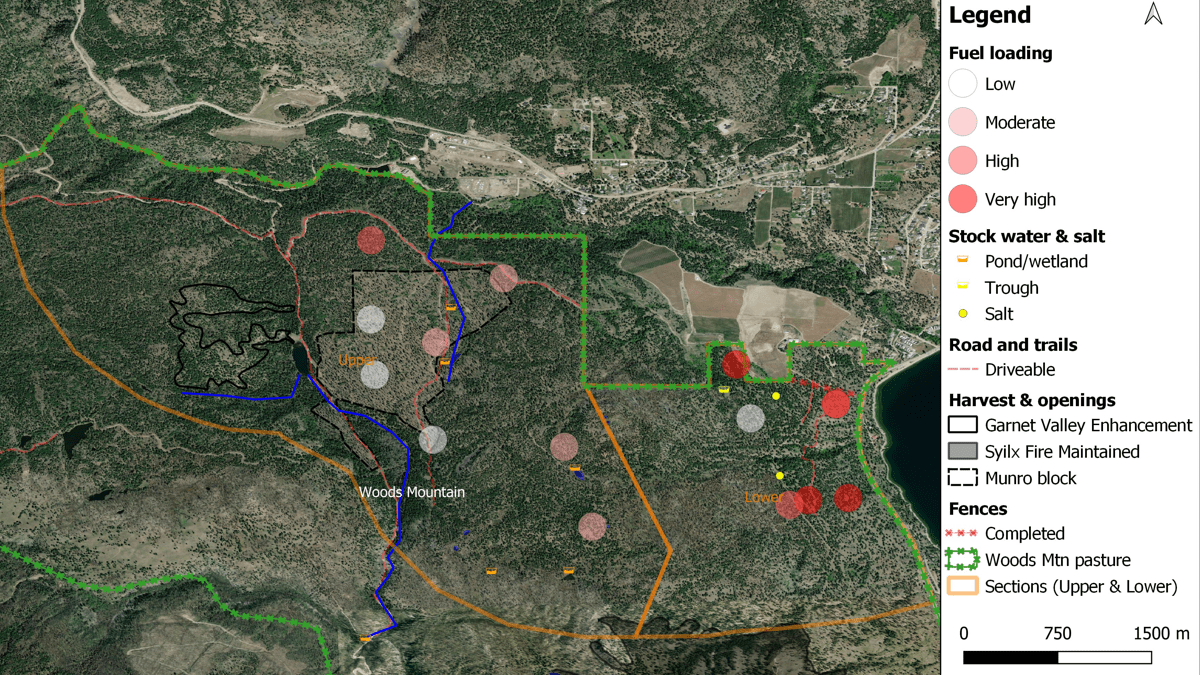

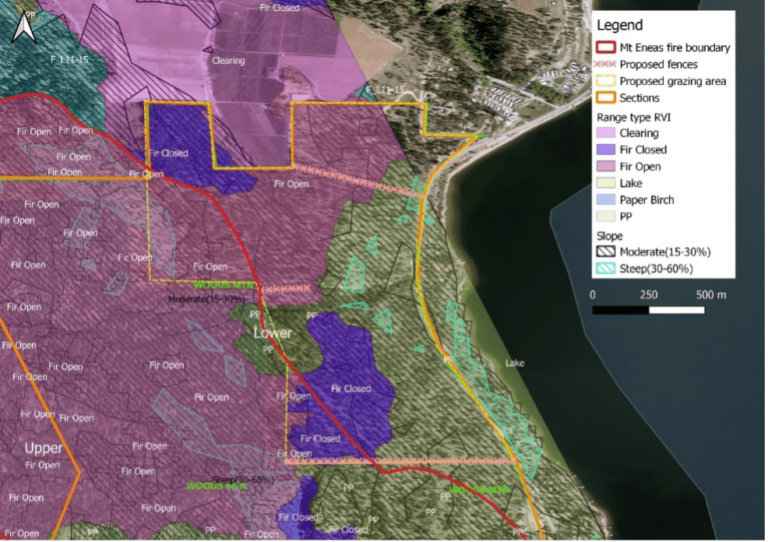

The researchers used field mapping tools and handheld devices to perform the initial and ongoing data collection on plant community cover, grass height, and changes in biomass as the grazing progressed. “We used GIS as basically a starting point for everything,” Miller said. “Mapping is a heavy component of this, and quantifying the data visually through mapping products is a huge part of communicating our grazing strategy and outcomes.”

GIS was an essential element, providing maps for the ranchers to plan their next grazing locations. “We use ArcGIS with the most recent orthoimagery that we have,” LaRade said. “Then we allocate forage production based on the vegetation types we observe within the treatment area.”

During the last few seasons, targeted grazing on each test site reduced fine fuels by approximately 30 percent. “The forest fuels clean up by cattle provides an extra level of protection,” Morrow said. “We look forward to working with local ranchers and agencies on similar win-win projects.”

The team has created heat maps to visualize the evolving fuel loads and track biomass reduction to demonstrate the program’s effectiveness. “It’s a really positive way of representing our work spatially, and it gets the message across,” Miller said.

Researchers involved in the project have partnered with the Ministry of Agriculture to document fuel reduction. “We use maps to monitor progress on the plots,” LaRade said. “We’ve got forest exclusion cages set up (to separate the ungrazed areas), and we’re looking at forage production in the cages versus outside the cages.”

The researchers are also monitoring grasslands and forest control environments to gauge outcomes of the program. “We have a lot of data to evaluate impacts to the ecosystem,” Miller said.

In the wildland-urban interface where the pilot project took place, mechanical harvesting was the first treatment to reduce the dense forests adjacent to the community. Grazing was the next treatment to reduce the grasses that arrived in the open spaces. In future years, prescribed fires will be conducted every 7 to 10 years to reduce the fuel load from any branches that have blown down. Fire will also rejuvenate the soil so grasses thrive and will eliminate younger trees so the area remains open and fire resilient.

Program managers and scientists continue to fine-tune strategies to find the right amount of grazing for the best outcomes on the land. If grazing is too intense, it can lead to the introduction of invasive species, such as the cheatgrass that’s taking over in other grasslands, including in Nevada.

Ranchers, too, are working to find a better system of moving the cows, because they currently have to erect and move temporary fencing, which is time-consuming and labor intensive. Virtual fencing, with collars on cows that can control their range and movement, is being tested in pilot projects elsewhere. This technological leap holds great promise to manage cows through the use of maps and remove some of the burden and costs. It ties into a trend of GIS for operational intelligence, with real-time maps being used to improve the efficiency and safety of complex projects because everyone can see what’s going on.

“Some of the tools that you can use for a greater understanding of what’s happening are pretty amazing,” LaRade said. “And people are accessing that information and creating this awareness that never existed before.”

The positive results have led to a lot of public interest and media coverage.

“It’s difficult for the ranching community to show how they improve the land,” LaRade said. “Once we started to see success, people were coming out of the woodwork to be involved, to partner, and to make it work.”

Learn more about how GIS can digitally transform natural resource management for greater sustainability.

August 23, 2022 |

January 25, 2022 |

November 30, 2021 |