August 6, 2024

The 2024 Climate Corps. Photo by Dr. Stephen Pinkney, courtesy of the Bullard Center.

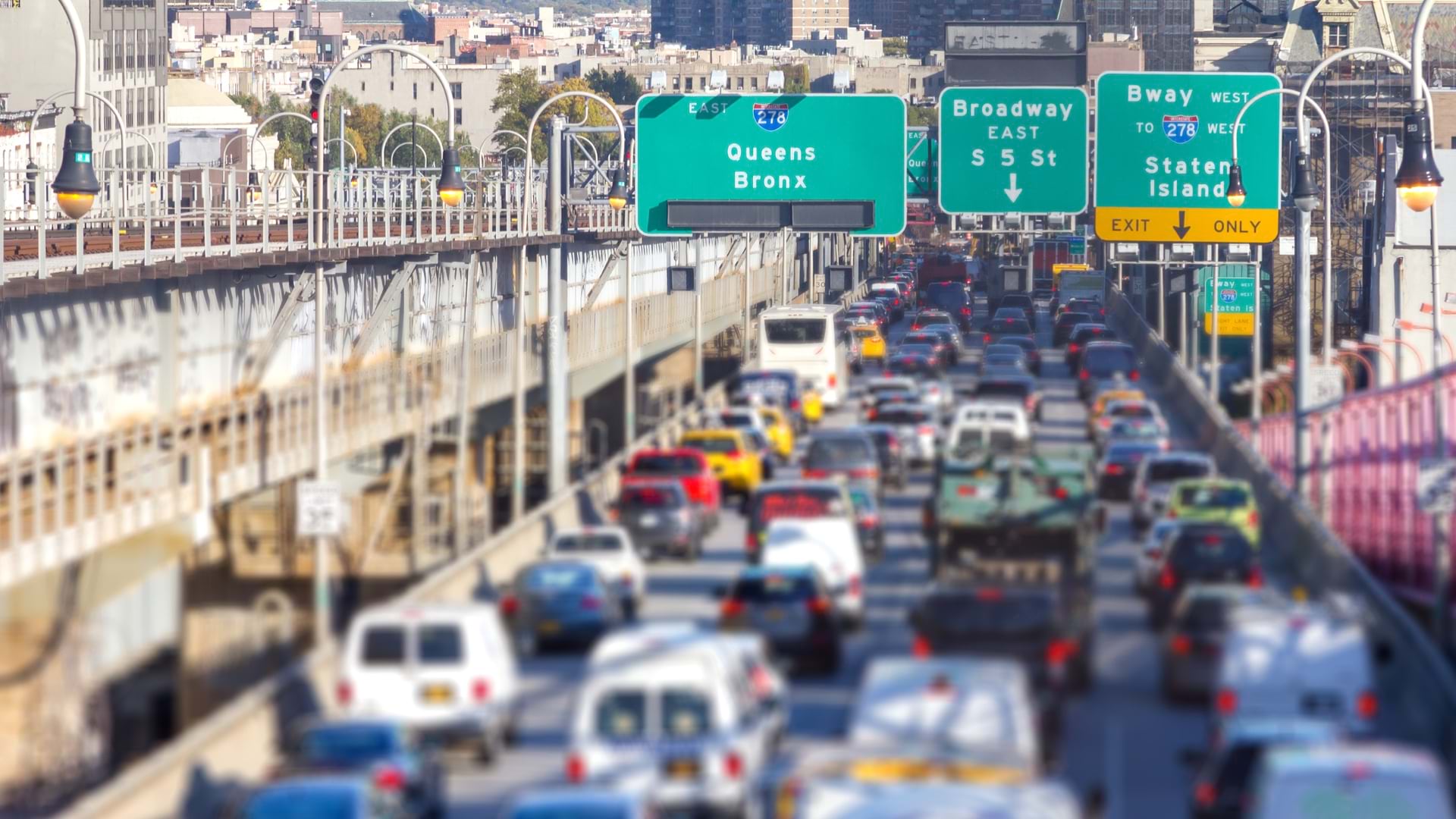

At the start of each annual Environmental Justice Climate Corps summer program, students from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) take the “Toxic Tour” through Houston’s East End. They travel to some of the world’s largest refineries, chemical plants, and hazardous waste sites that surround communities of color.

While there, students talk to Houston residents who face the highest rates of asthma and cancer. They see what the city’s pollution has done to the environment, such as how it stunts the trees.

When they get back to the classroom at Texas Southern University (TSU), they explore the mortality and makeup of the communities they grew up in, using geographic information system (GIS) technology to analyze place, race, and health layers on maps. Rooting these lesson in their own lived experience helps ignite passion and reveals data-driven discoveries about places they thought they knew deeply.

The program takes place at the Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice at TSU. Since the program’s inaugural summer in 2023, more than 30 students from 11 HBCU campuses across the country have been given the opportunity to gain knowledge and skills in GIS and to learn from Dr. Robert Bullard, who is known as the father of environmental justice. Dr. Bullard conducted pioneering investigative research, taught for nearly 40 years, and wrote 18 books, including Dumping in Dixie, which explores the concentration of landfills in communities of color across the South.

“Many of our students have no introduction to environmental or climate justice. Even though some grew up in the Houston area, they had never been to the Port of Houston,” said Denae King, an environmental justice researcher and associate director of the Bullard Center. “It’s a huge epiphany.”

In the same building as the Bullard Center, a GIS lab is maintained by the Urban Planning and Environmental Policy graduate program. The lab has 30 computers equipped with ArcGIS software, plus geospatial and demographic data about communities and the environment. Many students get their first exposure to GIS through the Environmental Justice Climate Corps program. “They understand how to use a map, how you explain data with a map, and what makes a map useful for a community,” King said.

Because the students in the summer program come from both science and non-science backgrounds, GIS is taught in a way that goes beyond the technology and moves quickly to real-life applications of the software.

“I always have to say to the students, ‘Where are the highways? Where are the schools?’” King said. “As a resident, I need to be able to look at the map and understand where I live and how this relates to me.”

In the 1990s, Bullard was called as an expert witness in a case his wife, attorney Linda McKeever Bullard, was involved in. She represented Margaret Bean in the lawsuit Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management in the fight against a municipal landfill in the mostly Black middle-class neighborhood of Northwood Manor. Bullard, fresh from receiving his PhD in sociology from Iowa State University, noted that all six municipal garbage dumps and six of the city’s eight incinerators were in Black neighborhoods. The successful case was the first recorded account of environmental racism, and maps played an important role in showing the harm to communities of color.

Since then, Bullard has continued to probe environmental racism, making it the focus of his career to show how toxins disproportionately impact people of color in their jobs and communities. Further, his work has demonstrated how environmental regulations don’t equally benefit society. In 2021, President Biden appointed Bullard to the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, and in April 2024 he was given a TIME Earth Award.

Bullard shows the students the impact of maps, overlaying public health data layers such as diabetes, obesity, and cancer onto communities of color. He shows how maps reveal the big picture.

In recent years, the fight for climate change and environmental justice has grown more urgent. Cities are increasingly experiencing extreme weather events like heat domes, floods, droughts, storms, and wildfires. These events often result in disproportionate numbers of Black and brown people dying from climate-related diseases like heat stroke and asthma. “We don’t teach environment in healthcare,” King said. “It’s not natural for a physician to ask you, ‘Where do you live and what are your potential environmental exposures?’”

Although the HBCU Environmental Justice Climate Corps is only in its second year of hosting students in the six-week program funded by the Macquarie Group, Bullard and TSU have been nurturing the next generation of climate justice activists for many years. The summer internship allows students to obtain a deeper understanding of mapmaking, environmental concerns, and community engagement practices.

“We’re helping students to understand it’s not just about creating a map, but creating a map that resonates with people, a map that they can look at and get the picture pretty quickly,” King said.

Last year, student-led projects focused on the issue of lead in the drinking water at Houston-area schools, along with air quality and petrochemical contamination. “The community needed us to look at air monitoring data. We cleaned, analyzed, and mapped the data to show trends,” King said.

This summer, students will hear from a data scientist who has mapped 90 proposed petrochemical facilities in the state of Texas. This work is part of the Beyond Petrochemicals project at the Bullard Center, with funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Another presentation will detail research on the location of liquid natural gas (LNG) facilities.

“We show them how mapping is actionable and how we use GIS in the environmental justice work we’re doing,” King said.

At the end of the program, students can participate in the HBCU Climate Change Conference. With the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, the Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice hosts the conference that brings together HBCU faculty, staff, researchers, climate and environmental justice leaders, and students to better understand the data and how people experience the intersection of environmental justice and climate change.

At the conference, student presentations cover a range of climate justice topics and related industries like energy sources, carbon emissions, green jobs, and economic development. “Our goal is to encourage them to get involved, to provide at least some information about environment and climate, to give them career options, and introduce them to research and presentation skills,” King said.

Of the 22 students who participated last year, 17 of them said they wanted to remain engaged in environmental work, and several TSU students started a campus organization related to climate justice.

“This spring for Earth Week, they did a week of activities. A lunch and learn, campus cleanup, a dorm recycle-thon, and they introduced new e-bikes that students can use around campus,” King said.

She hopes the program will continue to grow and add more students from various disciplines. “We want to pique their interest, to have them aware that environmental injustice is a problem that exists in people of color communities. We want them to know that there are solutions to the problem, and that they are part of the solution.”

Learn more about how environmental agencies use GIS to analyze impacts, monitor toxins, and facilitate community engagement.