November 23, 2021

When United States forces left Afghanistan last summer, 120,000 people were evacuated from the country over a period of a few weeks. While it was the largest airlift in US history, it still left thousands who feared for their lives as the Taliban advanced into Kabul.

Many of those looking for a way out were Afghan nationals who had formed close ties to Americans during the 20-year conflict that started soon after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Some worked as translators and in other support positions. Most feared Taliban reprisals, and a loss of freedom.

Prompted by requests from US servicemembers, defense mapping experts at two companies—Janes and Quiet Professionals—turned to geographic information system (GIS) technology to monitor the situation and help connect people to ways out. The experts’ adroit handling of maps and location intelligence is providing a solid foundation for the work of other groups extracting people from Afghanistan.

Mapping technology took leaps forward during the span of this conflict, with imagery and digital maps replacing paper-based products. Soldiers had become accustomed to communicating and collaborating across teams via shared maps, and now they used those tools to help people they feel indebted to.

Leo Kryszewski, chief of staff at Quiet Professionals, was deployed to Afghanistan with US Army special forces in 2001. He did several tours there and in Iraq, before leaving the service in 2009.

“Two weeks after the Twin Towers fell, I was in Afghanistan,” he said. “I met a lot of good people and formed a lot of close relationship, so this has all been very personal for me.”

Kryszewski works at Quiet Professionals with other veterans to provide mapping and technology support for military and intelligence organizations.

As the withdrawal and evacuation proceeded, Kryszewski and his colleagues had a feeling of helplessness. Needing a break from the news and social media, he walked over to the office of Andy Wilson, the company’s president and CEO. Wilson was also immersed in news reports. For a while, neither said a word.

“I’m standing there watching him pull his hair out,” Kryszewski recalled. “He said, ‘man, I wish there was a way to tie all these chats and information into one place.’ I said, ‘GIS.’ And that’s how it started.”

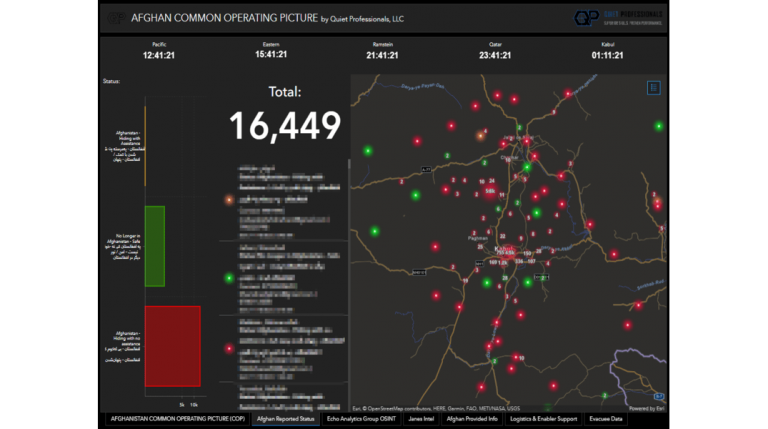

Quiet Professionals decided to build an evacuation tracker dashboard to capture and display data about who in Afghanistan needed help, what kind of help they needed, and where they were. At a tenuous time, GIS served as an information clearinghouse and a way to provide situational awareness to disparate teams and people. The dashboard came together quickly, without the procedural steps the company would typically take on a project.

“This was an emergency, a disaster, it couldn’t be something that rolls out three months after the event is over,” said Paul Bova, Quiet Professionals’ chief business officer. “It needed to go up immediately and it needed the right resources, because it was happening in real time.”

Cloud-based tools provided flexibility for the geographically dispersed team to iterate around the clock, adding information and features as the situation unfolded. Meanwhile, the crowds at the airport in Kabul were getting desperate.

“We launched it on a Thursday, and by Sunday we were tracking almost a thousand people,” said Malachi Keddington, vice president for strategic operations. “We knew we couldn’t slow down.”

It soon became clear that the site’s popularity warranted more context and additional data layers. For outside help, the Quiet Professionals team placed a call to Janes, an open-source defense intelligence provider with a 120-year history.

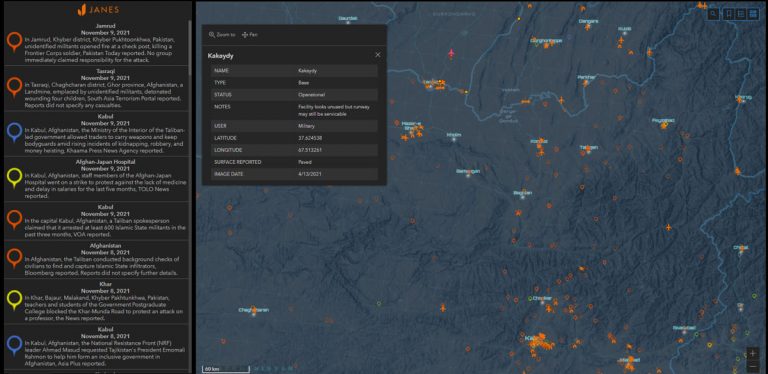

Janes specializes in what the intelligence community calls open-source intelligence (OSINT). All of the material is unclassified and available in the public domain, encompassing everything from newspapers and broadcasts, social media posts, and aerial imagery. Janes analysts are trained to sift through and make sense of this constant barrage of information, using the Janes tradecraft to verify and validate it, offering clients—which include both governments and private business—access to assured OSINT to guide decisions.

Over recent years Janes has interconnected its foundational military intelligence to speed data discovery. It recently hired a new chief product officer, Ben Conklin, with a GIS background. It was Conklin who fielded the call from an old colleague now working at Quiet Professionals.

Conklin applied his skills using ArcGIS Online to draw a more detailed map of Afghanistan. The major improvement was a new topographical layer that revealed the difficulty of maneuvering through the country’s varied terrain.

“It helps you understand that you have a city here and city there, and it looks like you can just go over land between them, but no, there are massive mountains between the two,” he explained.

The map of Afghanistan then became a map of people wanting to leave Afghanistan, with dots showing the location of people requesting assistance. The dots are color-coded to provide additional information and context, allowing anyone looking at the map to discern, for example, whether someone is in hiding, has a support network, or is in the process of being evacuated.

People in Afghanistan can register and provide updates to the OSINT Tracker via a simple ArcGIS Survey123 form accessible by a smart phone. This capability was also used to share real-time on-the-ground updates. Quiet Professionals makes that information available to government offices, such as the US State Department and Department of Homeland Security, as well as military organizations and NGOs.

“We’re not involved with any extraction process,” Bova clarified. “This is all about information gathering and information sharing. We’re providing technology that connects the right people with individuals who want to get out.”

As the OSINT Tracker’s reputation spread, managing it became a full-time affair, although still an all-volunteer endeavor. “We were working full days just on this, and at night doing our day jobs,” Kryszewski said.

Conklin brought in the team at Janes responsible for OSINT on real-time unfolding events, such as political unrest, invasions, and terrorist attacks. They all turned their attention to Afghanistan and the surrounding countries, gathering data that could augment the OSINT Tracker dashboard.

Like the Quiet Professionals team, Conklin realized that the unfolding situation demanded speed. Unlike them, the company he was working for was not his own.

“The person who could’ve really been upset about it is the guy who runs our research divisions, because it was his analysts I was using,” Conklin said. “But he loved it. He said it was one of the most impactful things he’d seen Janes do.”

Janes’ analysts used aerial and satellite imagery to monitor activities at checkpoints and border crossings. They provided detailed spatial analysis about the feasibility of different landing sites for evacuation missions.

“That turned out to be super-key data,” Conklin said, explaining that anyone looking at the Quiet Professionals dashboard can click on an airfield to learn more about the conditions. “For example, one of the places that has been used [for rescue operations] had an operational runway, but the facility itself was no longer in use. That’s actually perfect because that way you’re not disrupting normal air traffic.”

The data Janes gathered was crucial, but of equal importance was determining how best to integrate the data into the OSINT Tracker dashboard. The Janes team began by processing the data and providing it to Quiet Professionals.

“That made it so Janes could keep our content up-to-date, including the map design, and make it ready to use, and it would just show up on the Quiet Professionals dashboard,” Conklin explained.

As the amount of data collected by Janes increased, this workflow became inefficient. Janes designed a dashboard that could be effectively embedded within the OSINT Tracker dashboard that Quiet Professionals created.

“It was completely ready to use, and they didn’t have to do anything,” Conklin said. “It’s another tab in their dashboard, but we control it.”

This allowed Janes to contribute to the kind of shared perspective the company was not set up to provide.

“You couldn’t do this from the Janes website,” Conklin said. “It’s built for Janes customers, and there’s no common operational picture. But now I can push our data into this common picture because we have it as a feature service in ArcGIS. It validated what I already knew, which is that it’s really easy to use ArcGIS Online to merge two companies’ data.”

The most immediate purpose of the OSINT Tracker dashboard was to depict the ongoing crisis. For those hoping to leave Afghanistan, GIS offers further utility as a data storage system.

“If people go through the wrong checkpoint, they could lose their passport or other documents,” Kryszewski said. “We give them the opportunity to upload photos of the documents, so if they do lose them, they’re sitting here in a safe, secure environment. They can reach out, and after vetting, we can provide the documents for them.”

Even the confiscation of a cellphone need not be catastrophic. “We didn’t want people to have anything on their phone that could compromise them,” Keddington said. “And because Survey 123 is a web link, as soon as they hit submit there’s no traceback to what they submitted.”

Keddington noted that it’s the invisibility of the GIS aspect that makes the system work so well. “Web-based GIS allows you to offer the technology to the many people in the world who don’t know what it is and didn’t know they needed it,” he said. “All they have to do is fill out a little form, probably without even realizing that we’re able to manage their problem across multiple organizations and around the world.”

Two months after launching the OSINT Tracker dashboard, it was tracking 13,000 people across Afghanistan. Quiet Professionals and Janes have vowed to stay the course.

The scale of the effort recalls the team of teams management philosophy advanced by Gen. Stanley McChrystal, commander of the Joint Special Operations Command in the mid-2000s. By employing a shared cartographic framework, Quiet Professionals and Janes, in a very real sense, put everyone on the same map.

For the purposes of the Afghanistan rescue tool, the term “everyone” extends to those the tool is designed to help. Every interaction with the survey form adds a data point to the map, and by extension increases the overall knowledge the map imparts.

“We can put everyone on the same level, from government entities to NGOs to private individuals,” Keddington said. “It’s using geography as the common language.”