“We don’t just build maps. We build mappers.” That’s the tagline for Youth Mappers, a new global network of university students making maps that support international development projects that range from disaster to poverty relief.

Youth Mappers was formed under the auspices of the new Mapping for Resilience University Consortium, the founding members being Texas Tech University (TTU); George Washington University (GWU) in Washington, DC; and West Virginia University (WVU) in Morgantown, West Virginia. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID), a US government agency that works to end global poverty and foster democratic societies, awarded a $1 million grant to the consortium in late 2015. The agency, through its GeoCenter, directs which mapping projects the students work on according to its priorities.

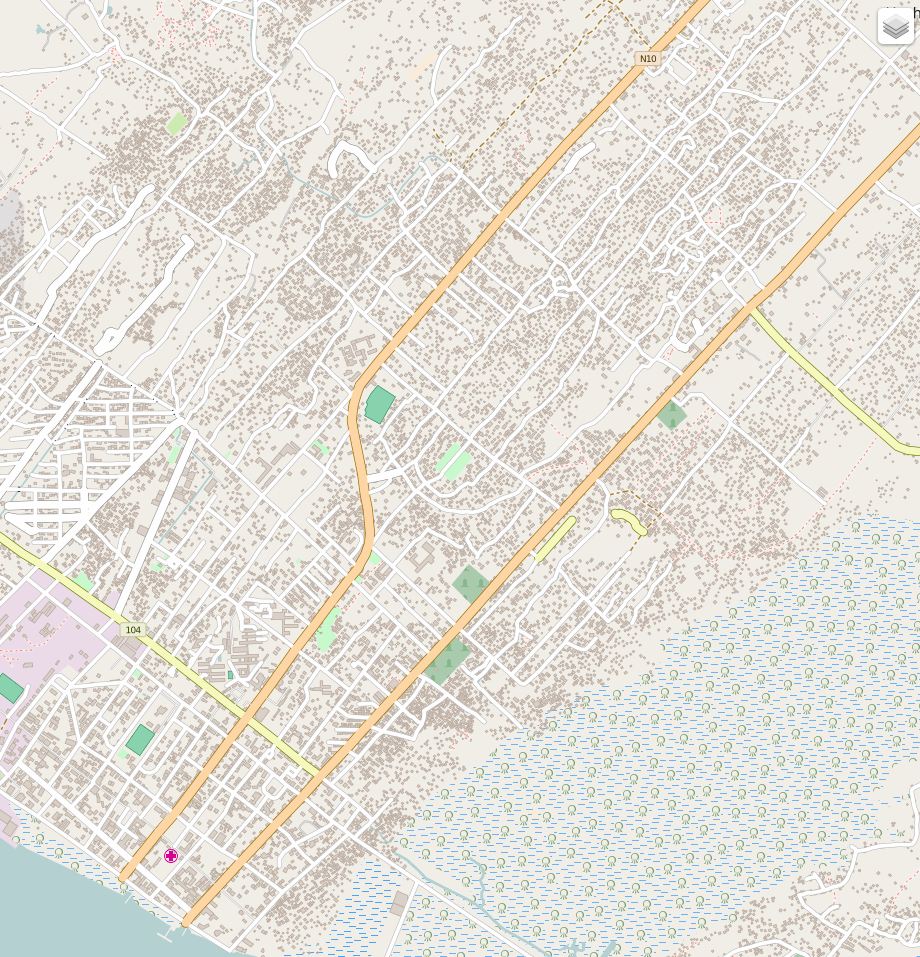

Already, the students are turning out maps that will do much good. For example, a group of Khulna University students in Bangladesh recently walked through a rural community near their city, noting the locations of ponds where people farm fish. Those locations, along with street names, were later added to a map of the area that was created digitally from satellite imagery by university students 8,000 miles away in the United States.

This mapped information, available on OpenStreetMap (OSM), will be analyzed by USAID to help strengthen food security for people living in the Khulna region.

The collaboration between the students in Bangladesh and the United States exemplifies the reason for the creation of Youth Mappers, a fledgling network of university-based chapters. Their work is spurred by what Youth Mappers project director Patricia Solis refers to as the “Geospatial Revolution 2.0,” a movement that’s galvanizing young people everywhere to change the world for the better by mapping it.

“It’s more than a technical revolution—it’s something of a social revolution too,” said Solis, who is also a research associate professor of geography at TTU in Lubbock, Texas. She said that students today often pitch in and work on volunteered geographic information (VGI) projects aimed at helping developing countries respond to natural disasters and fight problems such as poverty, disease, and hunger. In the process, they learn about other places in the world and get the opportunity to connect with students from these areas.

Universities in the United States and in countries where USAID works are welcome to join the consortium. Students worldwide can participate in Youth Mappers chapters, mapathons, and research fellowships to create geospatial data for USAID projects in parts of the world where few maps currently exist.

For example, TTU, GWU and WVU students recently collaborated to create a basemap of the seaport city of Quelimane, Mozambique, Africa. The map, now populated with roads and houses, will be used to plan an antimalaria campaign there. “If you can visualize the problems and visualize the solutions [with maps], that can bring us together to address development issues,” Solis said.

Development experts need maps for everything from finding their way around communities after a natural disaster to strategically planning their next project. USAID will use the student-made maps for projects that focus on increasing food security, preventing diseases such as malaria, and responding to natural disasters. USAID works in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, eastern Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

“In the United States, we are so used to having basic maps. That is not always the case in countries where USAID works,” said Carrie Stokes, director of USAID’s GeoCenter, which provides mapping and geospatial analysis services to USAID.

Building a Virtual Partnership

The GeoCenter is working with the consortium’s founding members to build what Stokes calls a “virtual partnership” between students in the United States and students in developing countries. The international cadre of student mappers will collaborate on making maps using OpenStreetMap. OSM is one of the basemaps available in Esri’s ArcGIS Online. Esri also offers a free, open-source add-on for ArcGIS for Desktop called ArcGIS Editor for OpenStreetMap (OSM Editor). Using OSM Editor, OSM data can be downloaded and analyzed in ArcGIS and changes can be uploaded to the OSM database if needed.

Students use high-resolution satellite imagery to map features such as roads, bodies of water, houses, and schools. Using OSM tools such as Field Papers or OpenMapKit, students who live in or near the cities and villages being mapped will go into the field to collect detailed information to add to the maps, such as road names, the number of students at schools, or types of building materials. All this information is made available for anyone to access on OSM.

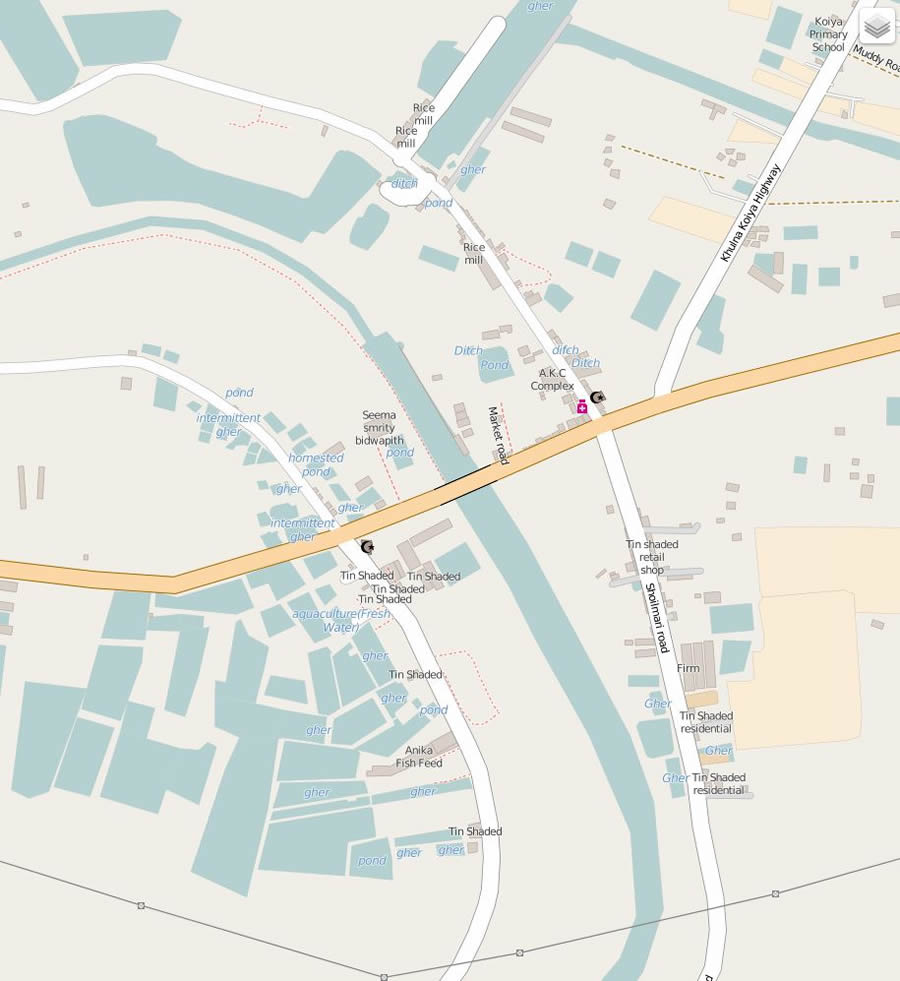

Khulna University students in Bangladesh were able to add that type of important detail to a basemap of a rural community near the city of Khulna, where the US government’s Feed the Future initiative operates. After TTU and GWU students created the initial basemap, the Bangladeshi students—led by GeoCenter analyst Chad Blevins—went into the field to do more mapping. They visited the area to collect detailed information, including the bodies of water where high protein foods such as fish and prawns are farmed. The map will help USAID better understand who has access to enough nutritious food to live healthy lives.

Students in developing countries know their land and communities well, meaning they add important information and perspective to the maps, according to Stokes. “Many people in poverty feel they don’t have a voice in their own governance,” she said. “Give them a skill to define their world by mapping it [and] they feel empowered.”

Stokes also pointed to a successful collaboration in 2013 between students at GWU and Kathmandu Living Labs, when the USAID GeoCenter and the World Bank’s disaster-risk reduction team helped map the city of Kathmandu, Nepal, to prepare for an earthquake. Nepal is very prone to earthquakes.

GWU students used satellite imagery to trace infrastructure such as roads and buildings. The mapping data was validated on the ground by Kathmandu Living Labs, which also collected attribute data to link to the mapping data.

When a magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck Nepal in April 2015, the GWU students returned to OpenStreetMap and continued to enhance the Nepal map, Stokes said. The GeoCenter downloaded the new map data onto GPS units that American search and rescue teams took to Kathmandu.

Creating Global Mappers

TTU, GWU, and WVU have hosted several mapathons to build maps requested by USAID. The events, which often advertise free pizza and training in how to trace features seen in the imagery to the mapping platform, attract a diverse crowd that includes students from outside the GIS and geography realm.

“It’s not just about tech. It’s really about making a difference in the world,” said Solis, who witnesses the students’ enthusiasm for these projects. “People care about people around the world when they know something about them,” she said.

And do they have fun? “We are talking about a gaming culture,” said Solis. “[Students] are motivated. They love the challenge of doing this. But most importantly, the learning potential for making real connections to other places and other students is profound. Youth Mappers not only builds maps—we also build mappers.”

A mapathon became lively in November, 2015 when TTU, GWU, and WVU students mapped the city of Quelimane. Using high resolution imagery that USAID provided the students competed to see which school could map the most features, including houses and roads. An estimated 26,000 buildings and more than 1,000 roads were put into OSM during that mapping effort.

The maps will be used in Mozambique to help malaria prevention workers plan where and how much insecticide to spray. “If you shortchange yourself by not having enough insecticide, said Stokes, “it affects the efficacy of the entire effort.”

Julia Kleine, the Youth Mappers chapter president at Texas Tech University, said the student group has great potential to help people in developing nations because of its international inclusiveness. “Youth Mappers gives people the opportunity to collaborate with students and youth from all over the world, ultimately creating a strong network of leaders in developed and developing nations that can face world issues together and be equipped with the tools to do so,” she said.

Most of the students drawn to Youth Mappers have a drive for change and a desire to give back to the world, said Kleine. This includes members from developing nations who are studying in the United States. “These students have personal reasons for getting involved as they have experienced firsthand the struggles of the developing world and the lack of access to geographical data,” Kleine said.

Many parts of the world remain unmapped, Stokes said, and the foundational basemaps the students create through Youth Mappers chapters will be vital to a variety of international development projects. USAID also expects that the Mapping for Resilience University Consortium will cultivate professionals with mapping skills, especially women from developing countries. The consortium plans to foster leadership roles for women.

The word resilience in the Mapping for Resilience University Consortium name underscores the importance of the consortium’s mission to help the people in the nearly 100 countries where USAID works. “We are trying to end extreme poverty and to help communities be more resilient [given] the many challenges they face, whether it is a drought, a change in government, an earthquake, or the changing climate,” Stokes said.

Stokes knows that the work the GeoCenter does with the consortium to train and mentor the young mappers will be critically important in the years ahead. “We are not only creating the next generation of maps for USAID but [also] the next generation of mappers for the world,” she said.

For more information about the Mapping for Resilience University Consortium, contact mappers.vpr@ttu.edu. For more information about the Youth Mappers chapters, visit youthmappers.org.