Native American Tribe works with Innovate! to Develop T-CRIS, Which Provides Compliance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act

More than 160 years ago, many members of the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians fled deep into the mountains of their traditional homeland between the Cascade and the Coast ranges in southwestern Oregon after the United States government tried to force them to relocate to reservations to the north.

Once landless, the tribe survived and ultimately thrived. Today its 1,900 members own more than 37,000 acres in southwestern Oregon. The land is used for agriculture, commercial ventures, housing, forestry operations, and other activities.

ArcGIS technology from Esri plays a crucial role in managing operations of tribal land, assets, and cultural resources, according to Jeremy Johnson, cultural resources program manager and tribal historic preservation officer for the tribe.

“The tribe tracks all of its property holdings, plans and manages its timber harvest activities, conducts scientific research and analysis for wildlife and fisheries, and houses its cultural and heritage databases [using] ArcGIS,” Johnson said.

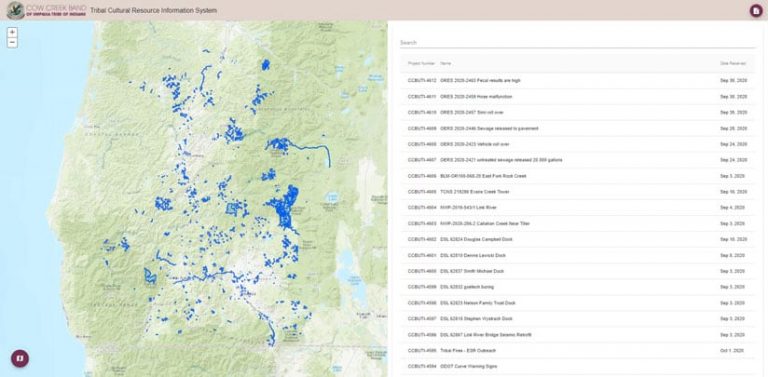

A case in point is the tribe’s Tribal-Cultural Resource Information System (T-CRIS), which was created using ArcGIS. The Cow Creek Band, with a tribal government office in Roseburg, Oregon, partnered with Innovate!, a geospatial consultancy headquartered in Alexandria, Virginia, to develop its web-based T-CRIS for managing, mapping, and reviewing hundreds of projects annually that may affect the tribe, be it culturally or in another way. T-CRIS, which launched in early 2019, uses ArcGIS software to store data on, create maps of, and visualize projects that impact the tribe, whether it involves a prescribed fire, reforestation, property rehabilitation, or an archaeology and cultural heritage program. The software for the project was made available to the tribe via the Department of the Interior-Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) Esri Enterprise License Agreement (ELA) and included ArcGIS Enterprise portal and ArcGIS Server.

A Look Back in Time

The mid-1800s was a time of much upheaval for the Cow Creek people. Hostilities were growing between the native population and the new settlers entering their land. So the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians sought a treaty with the US government and signed one in 1853 that required the tribe to cede more than 800 square miles of its territory to the United States in exchange for the promise of goods, services, annuities, and a reservation.

Until a permanent reservation was established, the tribe was offered a temporary reserve that consisted of two structures on five acres of land. This was the only part of the treaty that was upheld by the US government. As a result of the Rogue River War of 1855–1856, the US government decided that all Native Americans must leave southwestern Oregon and move to reservations in the northern part of the territory. That order prompted the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians to head into the mountains.

Eventually the tribe began buying back its ancestral land. Today the tribe operates business enterprises and a health and wellness center, and it collaborates with and provides feedback to federal agencies regarding projects that potentially impact tribal land. That’s where T-CRIS and its mapping capabilities come in.

Tribe Tracks Projects That Impact Its Cultural Resources

Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act requires federal agencies to go through a review process when initiating a project that might affect historic properties and cultural resources, including projects located on tribal land. It requires those agencies to consider the effects of their undertakings on historic properties and provide the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation with a reasonable opportunity to comment on their proposed work. In addition, federal agencies are required to consult with other agencies, such as the state historic preservation offices, tribal historic preservation offices, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations, before undertaking a project.

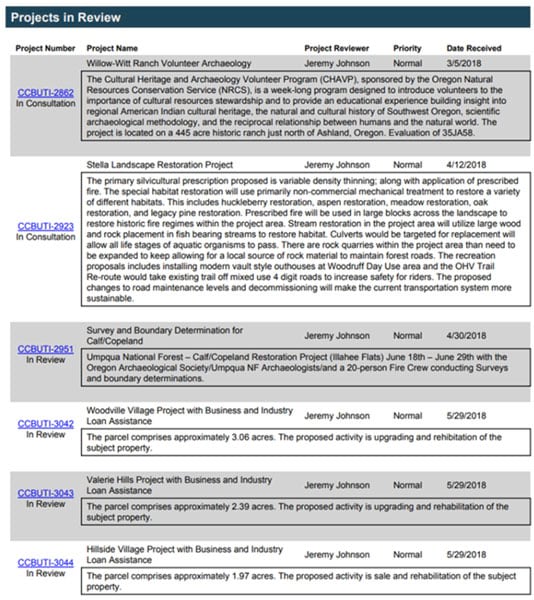

The Cow Creek Cultural Resources Program (CCCRP) reviews approximately 700 to 800 proposed projects each year and provides feedback to federal agencies on what effect, if any, there would be to the tribe.

The CCCRP initially used Microsoft Excel to manage these projects before moving to a Microsoft Access database. However, Johnson and his staff quickly realized the benefits of mapping each project to ensure that the cultural resources were being protected to the greatest possible extent, as well as examine the potential cumulative effects of a proposed project. Cumulative effects can occur to a specific resource over time when different projects take place at the same location. They are not typically considered when an agency develops a scope of work for a project, so mapping these projects is very important to the CCCRP.

The T-CRIS system houses a variety of information on the many project proposals that the CCCRP receives throughout the year.

“There is a SQL [Structured Query Language] component for entering and managing project information and an associated GIS component for the mapping of a project’s footprint,” Johnson said. “There is also a reporting component that queries the data in the system and provides reports based on the parameters selected.”

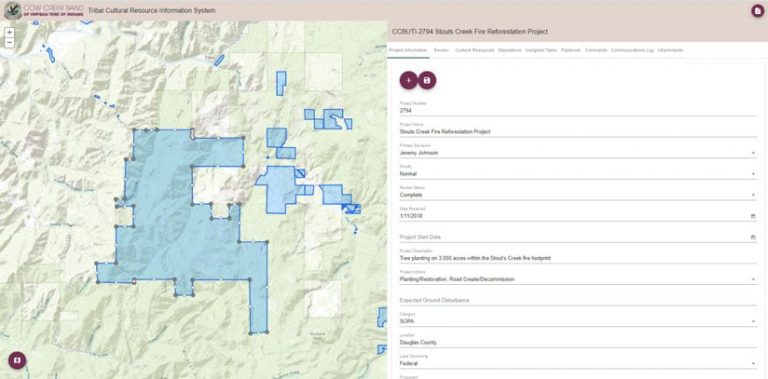

The system houses all the relevant information on a project to allow the CCCRP to complete the Section 106 process. Once a notification is received from a community partner or agency, staff are able to input the project details and map the project’s area of potential effect. From there, questions can be asked about the project such as the following:

- Is the project’s footprint within the Cow Creek Tribe’s ancestral territory?

- Are there significant cultural resources or sites within the footprint?

- Is there a high probability of unknown resources being present?

Based on the review that takes these questions into consideration, the project is moved through the steps of the review process.

“The CCCRP can then request stipulations or more information if there are any concerns and perceived impacts,” Johnson said.

If CCCRP staff needed to review a campground renovation project and were concerned that redundant work might be done at the site, they could go into T-CRIS and find a PDF that outlined what type of renovations were done during a past renovation.

“You just click the project’s shapefile and bring up the other project’s original PDF,” Johnson said.

Staff can consult maps when reviewing a project. For example, a wildfire burned in the area of Stouts Creek in Douglas County, Oregon, in 2015. Later, the Bureau of Land Management proposed a tree planting in the area. The CCCRP reviewed a map to see if there were any archaeological sites in that area that would be impacted, Johnson said. A review also might include a check to see if there are burial grounds in an area or if common camas plants are growing in that location. (Some Native American tribes consider camas bulbs a delicacy.)

Reports on environmental issues, such as gas leaks, are also mapped using T-CRIS.

“If a spill or contamination occurs, it can affect the community,” said Johnson, adding that T-CRIS has improved the workflow for the CCCRP.

“[T-CRIS] is a one-stop shop for project reviews,” Johnson said, adding that he can do the work faster than before. “Yes, it makes my job a whole lot easier.”