In His New Book, Martin O’Malley Says Good Governance Depends in Part on Strong Leadership, Collaboration, and Technologies Like GIS

“Map it. Believe it. See it,” wrote former Maryland governor Martin O’Malley in autographing a copy of his new book, Smarter Government: How to Govern for Results in the Information Age.

Measuring and managing performance—whether it’s to fight crime, improve public health, or fix potholes—are part of O’Malley’s governing philosophy. Mapping data on these types of issues using geographic information system (GIS) technology has been one of the core techniques he has used to do it.

Smarter Government, recently published by Esri Press, lays out O’Malley’s philosophy in full. He outlines his approach to leadership and governance as one that’s long on collaboration, transparency, accountability, and data-driven decision-making with help from supporting technologies like GIS.

“What the book is about is not so much the technology,” O’Malley said during an interview at the 2019 Esri User Conference, where he signed advance copies of his book. “We have better technology than a self-governing people have ever had in the history of the planet to measure, model, and map not only our built and natural environment but the human dynamic that unfolds across it and to be able to do it in ways that all can see. Those are relatively new tools. What we need, as fast as the technology has advanced, [is to] catch up with the sociotechnical habits of leadership and management and collaboration that allow us to deliver real tangible things—safer neighborhoods, cleaner water, better schools.”

The book is geared toward current and aspiring government leaders and others who work in public service. Though it mainly focuses on how to be an effective leader and achieve results using data-driven performance management and predictive analytics systems, readers also will find links to 35 online GIS exercises or tutorials.

This is O’Malley’s first book. It comes after a long political career, including roles as a city council member in Baltimore, the mayor of Baltimore, the governor of Maryland, and a candidate for president of the United States. He half jokes that it took him 23 years to write Smarter Government. But the material for the book became more focused as he prepared to teach at colleges and universities around the country, including a course he gave at Boston College Law School called Leadership and Data-Driven Government.

“It’s only in hindsight that you come to understand what you really knew when you were governing or what you thought you knew and didn’t fully understand,” O’Malley said.

Data and Maps Tell the Stories

Smarter Government describes how, as a mayor and later as a governor, O’Malley instituted a series of performance measurement and management systems, also known as Stat systems, for policing, public works, education, business and economic development, health, and the environment. Maps were a key component of those systems.

The implementation of the Stat systems was considered one of O’Malley’s signature accomplishments during his two terms as the mayor of Baltimore from 1999 to 2007 and two terms as the governor of Maryland from 2007 to 2015. These systems incorporated Esri ArcGIS technology, and the maps created using ArcGIS were used within government to gain insights into problems ranging from crimes such as homicides and robberies to environmental issues such as water pollution and lead poisoning.

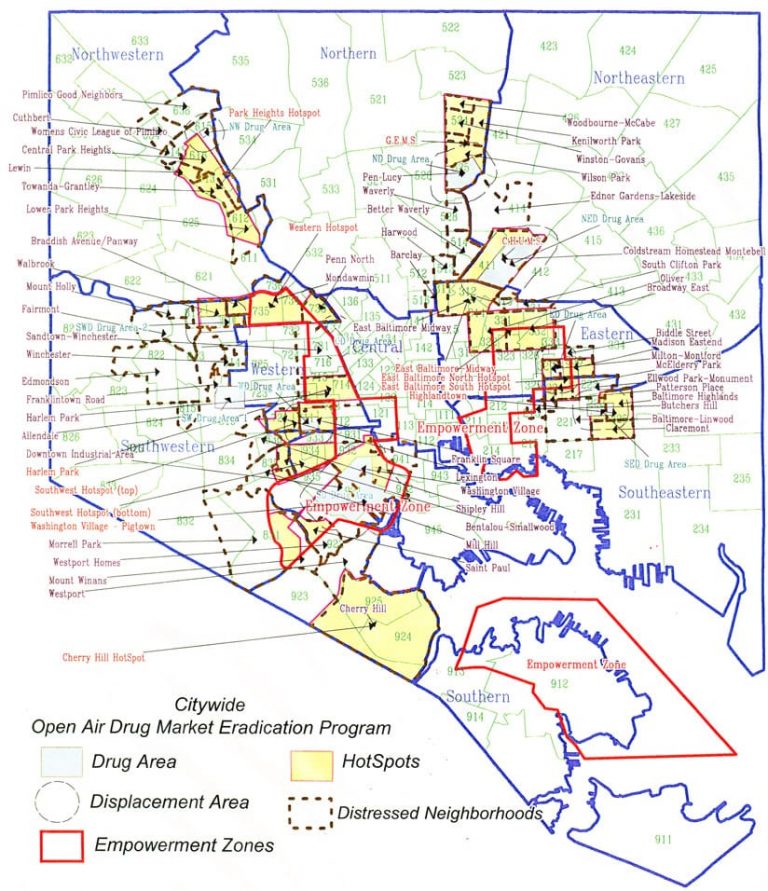

The maps also were used to measure a wide variety of concerns including infant mortality, drug overdose deaths, and land preservation.Using real-life examples as illustrations, O’Malley shows how he combined collaborative leadership techniques with the use of the Stat systems to achieve desired results, whether it was to shut open-air drug markets, reduce lead poisoning cases among children, or bring down the number of deaths caused by drug overdoses. Underpinning the performance measurement and management systems were the maps produced using ArcGIS.

As the inscription in the autographed book reflects, O’Malley believes that data, when mapped, can clearly show people the extent of problems or measure performance. Later, after intervention or adjustments, the maps can also tell stories about the progress being made.

“As human beings, we make sense of things from stories close to home,” O’Malley said. “And maps make things open, apparent, and visible to everyone.”

Enter Jack Maple

The first Stat system in the country, known as CompStat, was developed by New York City Police Department (NYPD) deputy commissioner Jack Maple. Maple started mapping crime on paper maps when he was a lieutenant for the New York City Transit Police and brought his methodology to the NYPD after being recruited by the city’s police commissioner, Bill Bratton, in the mid-1990s.

“Jack started doing something in his portion of the subway that led to pretty dramatic reductions in crime,” O’Malley recalled. “He started making, [using] just Magic Markers and paper, maps of where the crime was happening in real time in his portion of the subway. He called his Magic Marker on paper maps ‘Charts of the Future.’ He deployed [officers] to where he knew, based on the past, the purse snatchings and other sorts of crimes were most likely to happen.” This was a rough but early form of predictive policing.

O’Malley said that eventually Maple wound up at a software convention in Manhattan, saw a demonstration of ArcView GIS, a precursor to ArcGIS, and had the NYPD start using the software to plot crimes on a digital map. (Read this ArcNews article about the television show The District, which ran from 2000 to 2004, that featured Maple’s computer crime mapping system.)

In Baltimore, the O’Malley administration hired Maple as a consultant and launched its own version of CompStat to monitor and map crimes such as homicides, robberies, and drug dealing. The CitiStat system was then set up to map 3-1-1 calls about illegal dumping, blight, street maintenance, flooding, and trash pickup.

CitiStat was also used to monitor data on employee performance (ultimately reducing chronic absenteeism and tardiness) and overtime spending (leading to significant cuts of more than $1 million from the budget in five months). The city also used performance measurement tools such as GIS to analyze response times by the fire department and ambulance services, which resulted in the closure of several fire companies—which O’Malley said was sadly necessary to cut costs during a recessionary period.

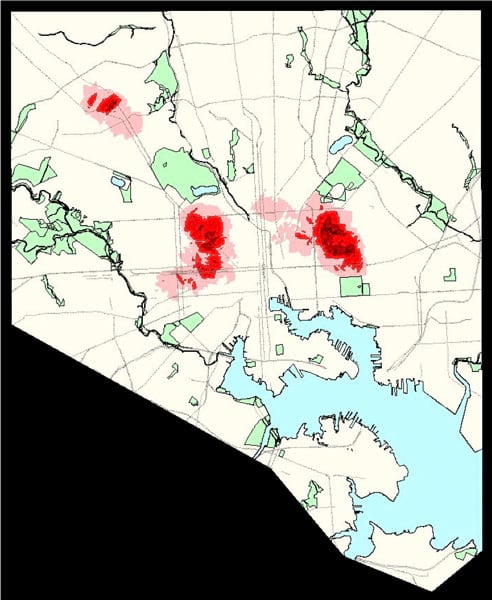

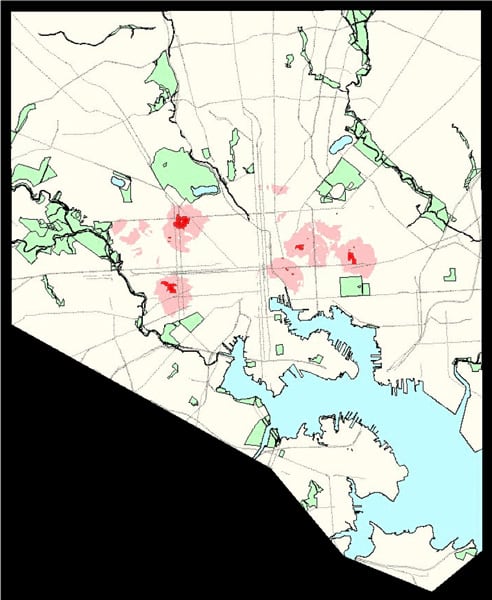

Some of the early Baltimore CompStat maps are printed in Smarter Government, including a series of crime heat maps for the years 1999 through 2007. Over time, the darker reds on the maps, indicating hot spots for homicides and shootings, faded to pink, signifying a reduction in shootings and homicides over the eight years.

While the use of GIS in performance measurement and management systems quickly spread throughout Baltimore city government after O’Malley became mayor, the Stat program started in the police department. There were reasons for that.

One, the homicide rate in the mid-1990s in Baltimore was high, with more than 300 people killed per year. “When I ran for mayor of Baltimore in 1999, our city had become the most violent, addicted, and abandoned city in America,” O’Malley said, adding that he was elected on his promise to turn things around.

The second reason was that Maple, the father of the NYPD’s CompStat system, though fighting cancer, was laser focused on and well versed in crime mapping.

“Even though he was suffering from a terminal diagnosis for colon cancer,” said O’Malley, “he agreed to come help me as our consultant to not only put police reforms in place and make our city safer but to take that same approach of the common platform—the data, the method, and the map—and do it enterprise wide.”

Though elated about his election, the new mayor knew he had big problems to deal with. “I had that moment like in the movie The Candidate, ‘Holy schnikes, I actually won!’ Now I have to govern,” O’Malley said.

One of the first things O’Malley and Maple tackled—having been one of the mayor’s campaign commitments—was to rid the city of the open-air drug markets that fomented much of the violence.

A CompStat map reprinted in the book shows all hot spots for crime in relation to the location of the open-air drug markets, which helped police officials, city leaders, and community activists decide which markets to target and close first. In the book, O’Malley said the decision on which 10 drug markets to close was both “collaborative and data based.”

Next, the City of Baltimore created the CitiStat system and meeting room, with computer screens on the wall for displaying relevant graphs and maps. There, O’Malley would meet with staff and tackle issues facing Baltimore in the early 2000s.

“For example,” he said, “when we had to figure out where to begin taking title to more than 14,000 vacant houses, we used a combination of data on different [map] layers to [decide] where are the places we should take title to [in order] to abate a nuisance. Where are the ones where we get the most frequent calls for service to board or clean? Let’s demolish those and prioritize.”

Citizen complaints coming in on the 311 system were mapped, too, such as graffiti sprayed on walls or trash dumped in an alley. Every two weeks, staff met to go over progress on these types of issues and view maps or graphs with data that O’Malley called “the latest emerging truth.”

Watch a video interview with O’Malley.

Information that had sat in silos in one department now appeared on maps with information from other departments. In that way, O’Malley’s team could begin to see patterns that would help them make smarter decisions.

“Everybody had to open their data and land the individual silos of information on the map,” O’Malley said. “It all became mapped, and that map became a living, breathing thing.”

Enter Jack Dangermond

Shortly after O’Malley became governor of Maryland, he met Esri president Jack Dangermond for the first time. He said Dangermond gave him a demonstration using empty coffee cups spread across a table to represent different silos of information from various departments.

“Jack said, ‘You’ve already figured out something that most elected leaders haven’t—you’ve realized that the map and GIS are a common powerful platform to combine those separate silos of information that everybody in government bemoans. If you land the base of all these efforts—all these separate silos of information—on the same map, then the map creates a picture, and then you can start running plays.'”

Run O’Malley did.

He instituted StateStat starting in 2007 to measure almost every facet of government performance including in the Maryland State Police and the departments of Health and Mental Hygiene; Juvenile Services; General Services; Labor, Licensing, and Regulation; Housing and Community Development; Business and Economic Development; Veterans Affairs; and the State Highway Department. BayStat was launched to monitor progress toward cleaning up pollution and restoring the oyster population in Chesapeake Bay, and DrugStat was started to measure the performance of drug treatment programs in Baltimore. Many of these systems relied on maps to gauge what was happening.

StateStat measured progress on 16 goals including childhood hunger, infant mortality, substance abuse, preventable hospitalizations, violent crime, and energy efficiency. Dashboards, some of which included maps that Esri helped create, were published online, showing where and whether or not progress was being made.

Transparency is critical to achieving good results, according to O’Malley.

“I see a new way of governing emerging all across our country and the world,” he said. “It’s rising up from smart cities where men and women who lead these cities have figured out that the new default setting is not to hold information but to make [it] open and transparent and clear and visible—to create dashboards not only for your internal use but [ones] that every citizen can see whether we are making progress or not.”

O’Malley sees his book as unique among the myriad of books written about leadership, management, and technology.

“This book is about leadership and management and the technology that makes more effective leadership possible,” O’Malley said. “So, it’s my hope that as the years progress, the book will be of service to men and women working in city, county, state, and federal governments—some of them might be frustrated at the leader at the so-called top who doesn’t appreciate the value of these new technologies and the value of a new way of governing. But that doesn’t mean that leaders in their part of the organization can’t do it. And maybe, like [what happened to] Jack Maple, somebody will notice their excellence. And then it becomes the way the entire enterprise goes.”

O’Malley said young people who take his class seem to get it.

“One of my students at the University of Maryland raised his hand and said, ‘All of the technology and all of that stuff is all great and everything, and I understand how we’ve never had it before, but it really doesn’t amount to a hill of beans without leadership.’ And I pointed at him and said, ‘Congratulations. A-plus . . . You have learned the entire point of the course.'”

Smarter Government: How to Govern for Results in the Information Age [print edition ISBN: 9781589485242 and e-book edition ISBN: 9781589485259, $39.99] is available from all major book retailers worldwide.

Watch a video interview with O’Malley.