Teaching and learning with GIS technology has always been focused on higher and more noble goals than simply learning GIS skills and tools. Learning GIS is an important skill set, but the ultimate goal is to understand an issue or a problem in a deeper, more holistic way and then communicate your findings and take action.

If you are a teacher who is considering adopting GIS software in your classroom, you may be wondering how your students would benefit by using GIS technology. The following 10 educational benefits of working with GIS opens up a world of possibilities for all learners.

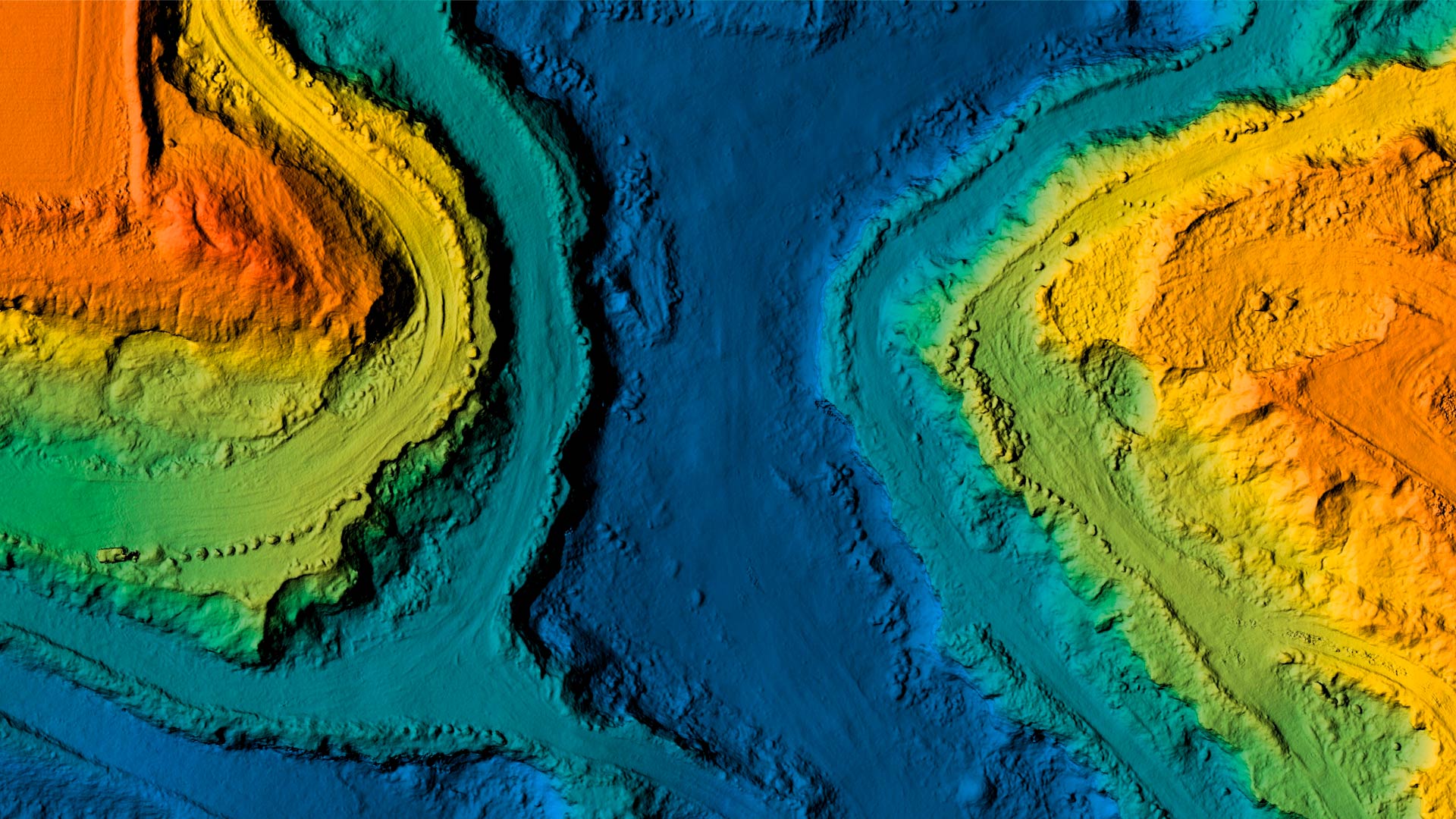

- Spatial Thinking—Maps have always been appealing, as they convey a large amount of information in a small amount of space. In the past, this space was always constrained by physical media—stone tablets, wood blocks, silver plates, film, and paper. Today’s digital maps are all around us, and they’re increasingly embedded in dashboards, interactive maps, articles, video, and multimedia of all types. They are in 2D and 3D representations, with the fourth dimension—time—increasingly enabled through animations and space-time cubes. Spatial thinking is crucial to understanding our increasingly interconnected, complex world, and it’s key to solving the serious problems we are facing in that world. Spatial thinking is greatly enabled by using the interactive maps made possible through GIS. Through GIS, students are not only consuming maps created by others, they are also creating their own maps, infographics, and web mapping applications and therefore deeply connecting with the creative process. Gaining the ability to think spatially, sometimes called graphicacy, is every bit as important to teach at all levels in education as numeracy, articulacy, and literacy, as educators and scholars have argued as long ago as 1971. Spatial thinking is coupled with holistic thinking, which considers the world as more than just the sum of its parts. It is also connected to seeing the world as a system of systems, including the biosphere, lithosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, cryosphere, and anthroposphere—the human sphere. Spatial thinking also fosters the understanding of cycles such as the carbon cycle and the hydrologic cycle. To learn more about topics related to geography, web mapping, and the power of spatial thinking, listen to episodes of the Thinking Spatially podcast series.

- Critical Thinking—Critical thinking must include three aspects: critical thinking about data, critical thinking about methods, and critical thinking about maps. Questions to pose as you teach with GIS include the following: What difference would changing the dataset theme, resolution, or scale make in the final analysis? Can you trust this map as a source for making a decision? Is this map or layer suitable for your project? Can you trust the data that you yourself collected in the field? What are the inherent errors in data—from map projections to missing attributes—and how can you manage these errors?

- Project Based Learning—GIS was created to solve problems. Using GIS in education helps students frame, visualize, and grapple with problems. It even enables students to create solutions to those problems, whether they are about natural hazards, climate, urban greenways, litter, energy, social inequity, or other complex issues of our day. Project Based Learning (PBL) implies active learning, and GIS is a natural fit because, when using GIS, students are actively engaged as scientists, planners, and other decision-makers. Students in PBL learn by actively engaging in real-world and personally meaningful projects. Using GIS, students have flexibility to choose projects and address the serious problems that they see in their community and their world.

- Geographic and Scientific Inquiry—Inquiry involves asking questions, gathering data, assessing the quality of that data, evaluating methods, analyzing the data and the results from each of the methods used, making decisions and recommendations, and taking action. This process usually sparks additional questions, and the process continues. The effective use of GIS is keenly tied to this process of inquiry. At its core, GIS has always been a thinker’s tool. GIS requires students to ask questions. Students aren’t used to asking their own questions; they are used to instructors asking them questions. How can we encourage students to ask thoughtful questions of their own? Read the ArcUser article, A Good Map Teaches You to Ask a Better Question. Asking questions leads to tenacity in problem solving, and those who ask questions are those who employers want to hire to help their organization achieve its goals.

- Data Fluency—The book Understanding the Digital Generation: Teaching and Learning in the New Digital Landscape stresses that to prepare students for today’s workplace, there must be a shift toward teaching skills that are tied to technology. Fluencies connected to technology and digital media should be emphasized. The book uses the word “fluency” rather than “literacy” because it conveys a sense of lifelong learning, such as becoming fluent in a language—in this case, the language of technology.

There are five important fluencies. Solution fluency is whole-brain thinking, including creativity and problem-solving applied in real time. Information fluency is the ability to access digital information sources to retrieve desired information and assess and critically evaluate the quality of information. Collaboration fluency—a teamwork proficiency—is, according to the book’s authors, the “ability to work cooperatively with virtual and real partners in an online environment to create original digital products.” Creativity fluency is, the authors say, the “process by which artistic proficiency adds meaning through design, art, and storytelling.” And media fluency is the ability to look analytically at any communication media to interpret the real message, determine how the chosen media is being used to shape thinking, evaluate the efficacy of the message, and publish original digital products to match the media to the intended message.

When students use GIS and geographic inquiry to grapple with problems, as I have witnessed thousands of times over the past 20 years, students engage in all five of these fluencies. Creating interactive maps alone is key to creative fluency, and thinking critically about maps is key to success with media fluency as well as many aspects of modern life.

6. Community Connection—GIS is a tool used worldwide to help better understand global challenges such as climate, education, water, and other issues addressed in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). But at the same time, GIS is a tool that students and educators can use to engage on issues at the local level, such as planning a new bike trail, nurturing public art or community gardens, or tackling traffic accidents or graffiti. With the rise of community data portals such as ArcGIS Hub, engagement software as a service from Esri; indicators in real time of what is happening on, under the surface of, and over the planet; and students’ ability to collect their own data, there is no shortage of data to examine, map, and use in understanding and engaging with local issues.

- Mobile Workforces—Work being performed away from the classroom needs to include using field methods and getting outside! This type of work is essential not only for understanding our changing world and our communities but also for nurturing an Earth-focused ethic in students so that they will appreciate and want to care for the marvelous planet on which we live. Implementing successful field activities involves planning and executing the work and analyzing the results. It is keenly tied to project planning, dealing with uncertainty, working with high- and low-tech methods, and managing data—the units that will be used; the variables; and the resultant data tables, images, geodatabases, and maps. It sometimes involves contacting others in the community for access to certain lands or to garner their support and participation. Students can use ArcGIS Survey123, ArcGIS Field Maps, or other Esri GIS apps, along with citizen science apps such as iNaturalist and apps for identifying ambient sounds or plant species, then bring the data into the ArcGIS environment for spatial analysis. The work of mobile teams was an integral part, for example, of a recent Data Citizens Western New York project in which students and faculty mapped storm drains and learned about the water and sewage system of their own community. This type of work, even if it is just on the school or university campus, involves the act of getting outside and observing, using tech tools as well as one’s own five senses.

- Career Pathways—Students often ask, “When are we ever going to use this after we get out of school?” While we shouldn’t use GIS in education just because it is in demand in the workplace, we should recognize that GIS does provide students with career skills that will never go out of style. Students who use GIS become valuable employees for nonprofit organizations; academia; government agencies, ranging from local to international; and private industry. They are able to make decisions, work with data, and see holistically. Sustainability and resilience will be in every organization’s plan in the future, and GIS will always have a key role. Furthermore, I have seen, time and time again, how students rise to the occasion and achieve more because they know they are using a set of tools that are being used in the professional community. Play these career videos and podcasts that highlight intriguing people who use GIS in their day-to-day work.

- Content Knowledge—When you are teaching and learning with GIS, you are gaining core content knowledge. GIS was never about “buttonology”—the practice of memorizing where tools and buttons are on the GIS interface and learning how to use them. Even if you are teaching and learning in a GIS or geographic information science (GIScience) course, every procedure has real data behind it, so you are concurrently learning about plate tectonics, ecoregions, climate, the hydrologic network, transportation, energy, city zoning, or other aspects of our natural and human-built world. GIS is core to science, including social science. GIS also is rapidly expanding outside of geography and planning to fields such as health, business, civil engineering, data science, history, and the humanities. Students acquire content knowledge more rapidly than by memorizing large volumes of information because they are actively engaging with the data and methods as a practicing professional would.

- Students as Change Agents—Students empowered with the skills, content knowledge, and perspectives detailed in this article have the confidence and ability to become change agents in their future workplace. Given the examples—such as at a high school and a community college—detailed in the Esri user community space over the years, students are already change agents in their own schools, universities, and beyond. GIS can also serve to help women and people in other underrepresented populations step into technology-based careers. To learn more about several inspiring women in the geospatial community, check out the GeoInspirations series of articles and podcasts.

If you are a primary or secondary school teacher thinking about using GIS technology in your classroom, you should know that Esri offers a mapping software bundle at no cost for instructional use to individual K–12 schools and school districts in all US states. The software also can be acquired by schools worldwide at no cost by contacting one of Esri’s international distributors. If you are teaching in a technical, tribal, or community college or university, chances are that your institution already has access to Esri technology. To find out, contact the Esri education team via esri.com/education.

The questions of why and where will be increasingly asked in all aspects of the workforce in the coming years. We are faced with pressure on our one single planet for which there is no spare. Teaching with GIS not only brings the benefits detailed in this article but also—even more importantly—empowers students to be effective decision-makers in our complex, dynamic world.