A city steeped in history has a responsibility to tell its stories.

Like the story of the Rev. Thomas Milton Allen. He was born into slavery in 1833; became the pastor of Zion Baptist Church of Marietta, Georgia; died in 1909; and was buried in the Marietta City Cemetery. Or the story of William Root. He was born in 1815, became the city’s first druggist, and whose legacy as one of Marietta’s earliest merchants lives on at the William Root House Museum and Garden. He died in 1891 and was buried in Marietta City Cemetery.

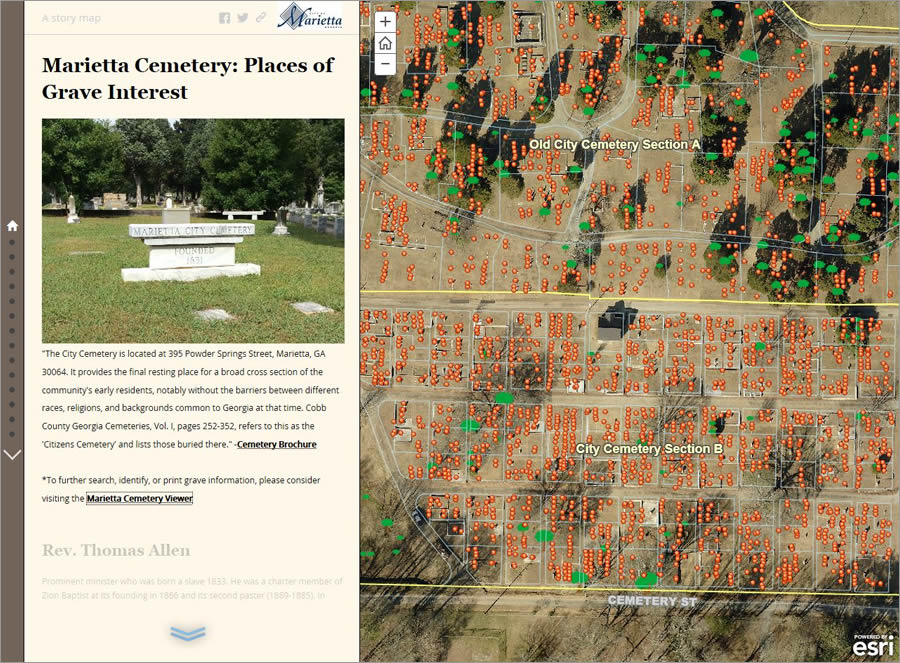

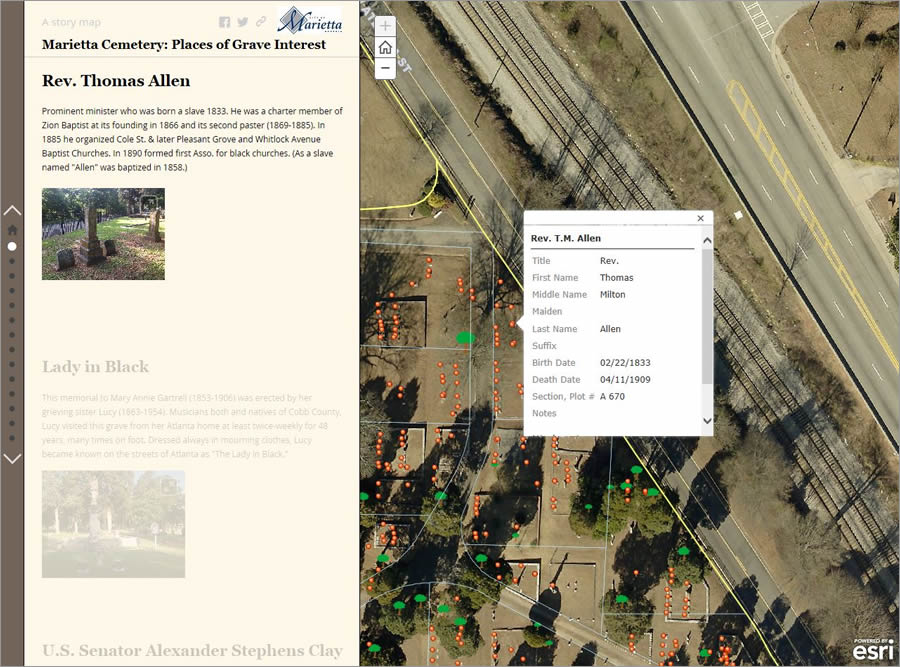

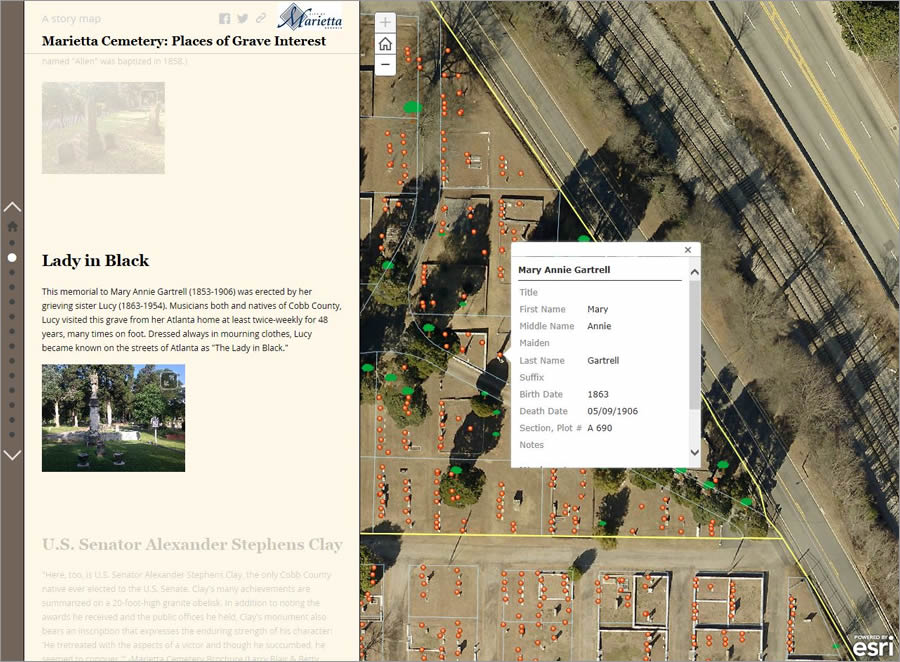

Stories like this come alive in Marietta Cemetery: Places of Grave Interest, an Esri Story Map Journal created by the City of Marietta’s GIS Team. The Story Map Journal displays the location of the graves of people buried in the Old City Cemetery. Pop-ups on the map show their names, birth and death dates, and the plot number of their grave. Stories about several notable deceased residents of the city are told, along with the meanings behind some of the grave symbols such as lambs (sometimes seen on children’s gravestones to mean innocence), and wings with crest (denoting the final resting place of a US Air Force pilot).

How did the data come to life on a map? The story begins with the people of Marietta, who wanted to help fulfill a storytelling responsibility for their city, a pre-Civil War suburb of Atlanta and home to almost 60,000 people. The city decided to do this by improving the city’s grave marker data and highlighting the lives of the people buried in its local cemetery. To collect the data, improve it, and share it with the public, the city turned to its GIS department and ArcGIS from Esri.

With 4,500 grave markers of deceased people to locate and collect information about, Marietta’s GIS staff faced an uphill challenge. The team needed to find ways to add recent burials, increase grave marker location accuracy, and attach photos to an existing grave marker layer in its GIS—without access to wireless Internet or cellular connections.

Nothing Set in Stone

The GIS staff first tried geotagging the photos, which entails attaching coordinates to digital images. Because mobile devices with geotagging capabilities were readily available, the staff tested geotagging on a few grave markers.

But problems arose. First, the accuracy of the coordinates of the grave markers wasn’t high enough to differentiate between each one. Second, the coordinates only could be added to the images when the devices could access wireless Internet or a cellular signal. Since there was no wireless Internet connection at the cemetery and acquiring a cellular data plan exceeded the project’s scope, the staff buried the idea of geotagging.

A Solution Appears

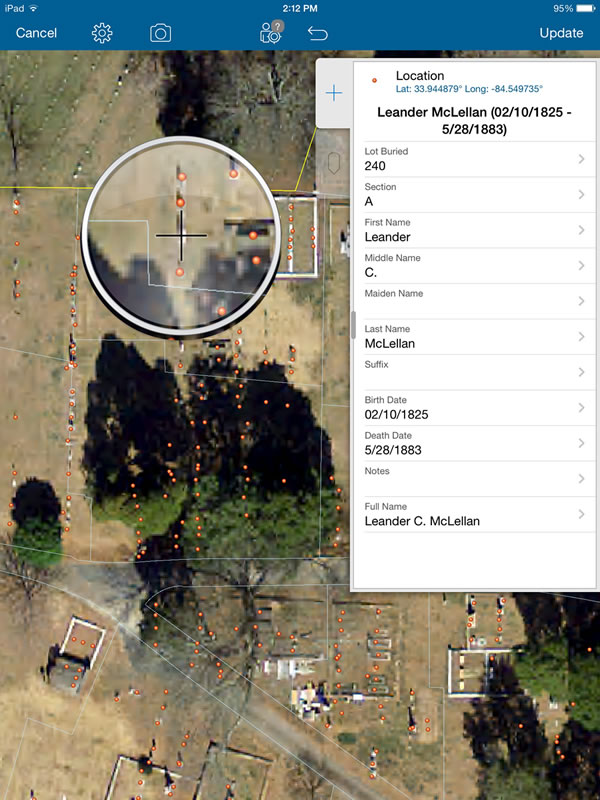

Just like the original sculptors of the cemetery’s ornate grave markers, the city’s GIS staff needed to use all of its available tools to improve the accuracy of its grave marker data. Rather than stone, chisels, brick, and mortar, the staff assembled tablets, Esri’s Collector for ArcGIS, off-site wireless Internet, and an ArcGIS Onlineorganizational account. Soon, a mobile editing workflow began to materialize.

ArcGIS Online would host the grave marker locations, along with imagery of the cemetery. Before leaving the range of city hall’s wireless Internet signal, staff created the editable feature layer and cached imagery from ArcGIS Online for use with Collector for ArcGIS in the field. This gave the team of six city employees, volunteers, and interns assigned to the mapping project the ability to use Collector for ArcGIS to collect data while offline so they could:

- Add new grave markers to the map.

- Move existing ones to more accurate locations (based on the aerial image).

- Take photos of each grave marker and attach those photos to each grave marker point.

- Temporarily store all the collected data on each tablet.

All this was done without a wireless Internet signal. Additionally, upon returning from the cemetery, the team members could use city hall’s wireless Internet connection to synchronize their collected data with the city’s ArcGIS Online hosted data. The data collected in the field was used to update the feature layer and create a live map and story map.

Data Collection Gets Off the Ground

With a mobile editing workflow in place, the team members began to visit the cemetery. While the transition from the bustling, air-conditioned, Internet-connected offices of city hall to the quiet, humid, disconnected grounds of the city cemetery took some rigor, it was only a fraction of the toughness and grit that the buried individuals exhibited over their lifetimes.

The people on the team took photos of each grave marker reverently, keeping in mind the perspectives of surviving family members, historians, and genealogical explorers. Processing about 35 graves per hour, the team made short work of the data collection, and the synchronized data began to fill the hosted ArcGIS Online grave marker layer.

Once the majority of the data was collected, it was time to start highlighting some of the special stories from Marietta’s past.

Telling a Ghost Story (Map)

Hosting data in ArcGIS Online not only made mobile editing possible but also allowed the GIS staff to easily build a hosted web application that the public could access. Using Esri Story Map apps, the team merged its newly collected data with historical narratives and vintage photographs.

Stories began to take shape. Within a few hours, a polished Esri Story Map Journal was created and published. People who view it will learn about Rev. Allen, who helped found several churches. And they will read about Mary Gartrell, whose sister Lucy, for 48 years, walked from Atlanta to Marietta to visit Gartrell’s grave. Because Lucy always dressed in mourning attire, she became known as the “Lady in Black.”

People could also now find out that Steadman V. Sanford, the namesake of the University of Georgia’s famed football stadium, and Alexander Stephens Clay, the first US senator from the area, are both buried in the Marietta Cemetery. The staff even highlighted extraordinary trees—those quiet witnesses to history—such as the water oak that boasts the cemetery’s largest canopy of over 86 feet.

The Story Map Journal was exactly what the city needed to present the cemetery’s fascinating history in an electronic format.

When the End Is Not the End

Since the City of Marietta places great value and respect on the breadth of its history, the decision to improve and highlight aspects of its cemetery was easy. The challenges arose when determining how best to bring the stories of the past into the modern, technological present. The City of Marietta’s GIS team faced these challenges head on and successfully deployed a host of Esri tools—with both online and offline functionality—to achieve its goals.

As the people alive today make new history, Marietta can build on its revamped technological foundation and continue to accept its responsibility to keep the stories of the past alive.