Typhoon Merbok struck Alaska on September 17, 2022, ferociously clawing its way across more than 1,300 miles of the state’s coastline. In places, pummeling winds ripped siding and roofs off buildings while rising water and pounding rain unmoored houses from their foundations, flooded roads, and broke apart the landscape. The National Weather Service would come to describe Merbok as “historically powerful.” Despite the disastrous conditions, no resident lost their life. However, over the course of that one weekend, erosion stole more than 100 feet of coastline in places, exceeding loss that wasn’t supposed to happen for decades.

Events such as Typhoon Merbok are top of mind for GIS professionals like Ellie Hakari, a GIS analyst for the State of Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (DOT&PF) who uses GIS to monitor the present and future conditions of Alaska’s roads. More importantly, she seeks to reduce risk to people who are impacted when roads fail as a result of natural disasters like Merbok.

The typhoon is just one of a number of natural disasters that have struck Alaska in recent years. “We also had a massive earthquake in 2018 that destroyed roads,” Hakari noted, “which was a big deal considering that even our largest cities are typically ‘one way in, one way out.’”

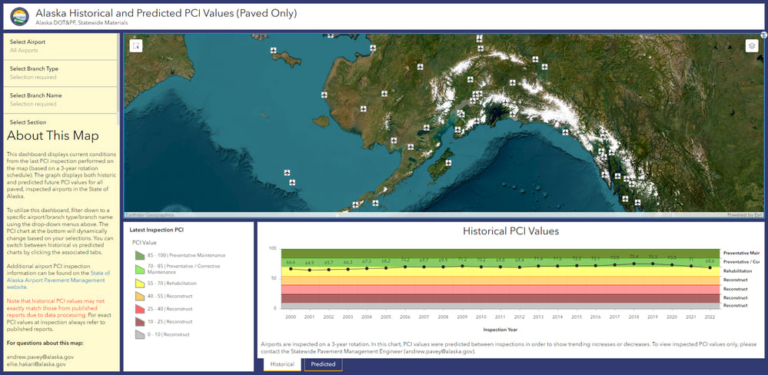

GIS was instrumental in the response to each of these cases, as well as the wildfires, floods, windstorms, and ice storms that have wracked the region and its infrastructure in recent years. “[We use] maps to communicate locations, ArcGIS Survey123 to collect information from our staff and the public, ArcGIS Dashboards to filter for priorities, and ArcGIS StoryMaps to track and communicate progress,” said Hakari.

Hakari—who now works for Alaska DOT&PF’s Southcoast Region Materials Group, a division that oversees geotechnical assets along Alaska’s southern coastline—is a consummate professional with a strong grasp of GIS software. But unlike many of her colleagues, she doesn’t come from a formal GIS background. Hakari was able to get where she is by taking advantage of resources like Esri Community, Esri training courses, and other easily accessible GIS educational resources. Hakari’s experience is a testament to how many different paths lead to careers where driven people can help affect change with GIS technology.

A Winding Career Path

From civil engineering to early education, computer sciences, ballet, theater, arts, and music, Hakari spent her college years sampling a variety of possible careers. Like many people navigating that early crossroads, committing to a single direction was anything but easy.

During her exploration, Hakari came across an internship that quickly turned into a full-time materials technician position.

“It’s dirt shaking, as we call it.” Hakari said. “Kind of learning about how asphalt is pulled together.”

In this work, she found herself surrounded by engineers who were just beginning to leverage GIS in their work in new ways. With GIS technology, they could supplement CAD linework with aerial imagery, pavement conditions, and more, making it easier to communicate details about various projects. Witnessing its applications in action firsthand—those that combined her love for art and math—Hakari developed an interest in learning more about GIS.

“I had a coworker who was heading that GIS effort at the time,” said Hakari. “Because I was new and an intern, I don’t think he took me seriously. He just kind of threw an ArcMap textbook on the desk in front of me and was like, ‘OK, just read through this front to back, you’ll learn some stuff.’”

Instead of relying on textbooks alone, Hakari turned to the internet to see what other people in the GIS world were doing.

“That’s when I came across Esri Community, and it just blew open the doors. I learned everything I could. I soaked it all in and asked questions. People were more than happy to give me answers and that drove all my learning and experience.”

From there, Hakari began attending Esri training sessions, lectures, and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), and took advantage of available documentation for ArcGIS tools and software to apply the material covered in her own work. As a self-professed visual learner, Hakari also found tremendous value in Esri-curated galleries of dashboards and StoryMaps created with ArcGIS software.

“Since the beginning of my journey in GIS, I have come at every project with the goal of effective communication,” said Hakari. “What’s the point of all your data and analyses if no one can understand the end product? I regularly review Esri’s gallery examples and apply what I see to my own work.”

In addition to connecting with other GIS professionals through Esri Community—a resource she still regularly visits—Hakari has also found education and community through these galleries, reaching out to creators to find out how they put together their projects.

“It’s clear that the passion Esri employees have for what they do reverberates throughout the GIS community and instills that same passion in others,” she said.

Developing Nationwide Road Resilience

In 2022, Hakari was nominated to be on a project run by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. Through this, she and a select group of participants have focused on developing resources that can be used by transportation agencies across the country to assess risks to their assets and the public due to extreme weather like Typhoon Merbok, climate change, and other threats or hazards.

“I got in the room with all of these incredible people who are directors—you know, top level individuals—and engineers who have been in the field for decades,” said Hakari. “I was thinking: ‘What am I doing here?’”

But many of the people she found herself speaking to and hearing from worked in roles facing climate change. Like her, they were and are acutely tuned to the position of peril it poses to their own states and were seeking solutions.

The group was aware of the central role GIS could play in the work before them. Hakari’s understanding of data level analysis and processing that she had developed along her unorthodox path to GIS would generate crucial insights needed to prepare their risk and resilience manual that would help organizations like hers across the country prepare for more typhoons, wildfires, and other natural disasters.

Hakari’s non-traditional route to GIS has, at times, struck her as contrasting with those around her—other GIS analysts, engineers, and geologists—people who went to school for what they wanted to do and confidently stayed that course into the heart of their careers.

But when she asked Esri Community members how many of them had fallen into a GIS career without a degree, she found her own experience reflected back at her, a snapshot of all the different paths that lead people to GIS.

“We had biologists and journalists, people working in criminal justice,” said Hakari. “[There were] so many different avenues people started in that eventually morphed into GIS. I think it speaks to just how useful GIS is in just about everything.”