The NGA’s Frank Avila Talks about a Career in Imagery and What the Future Holds for Imagery Science and Geospatial Intelligence

On airplane flights, Frank Avila always liked to peer out the windows and study the terrain thousands of feet below.

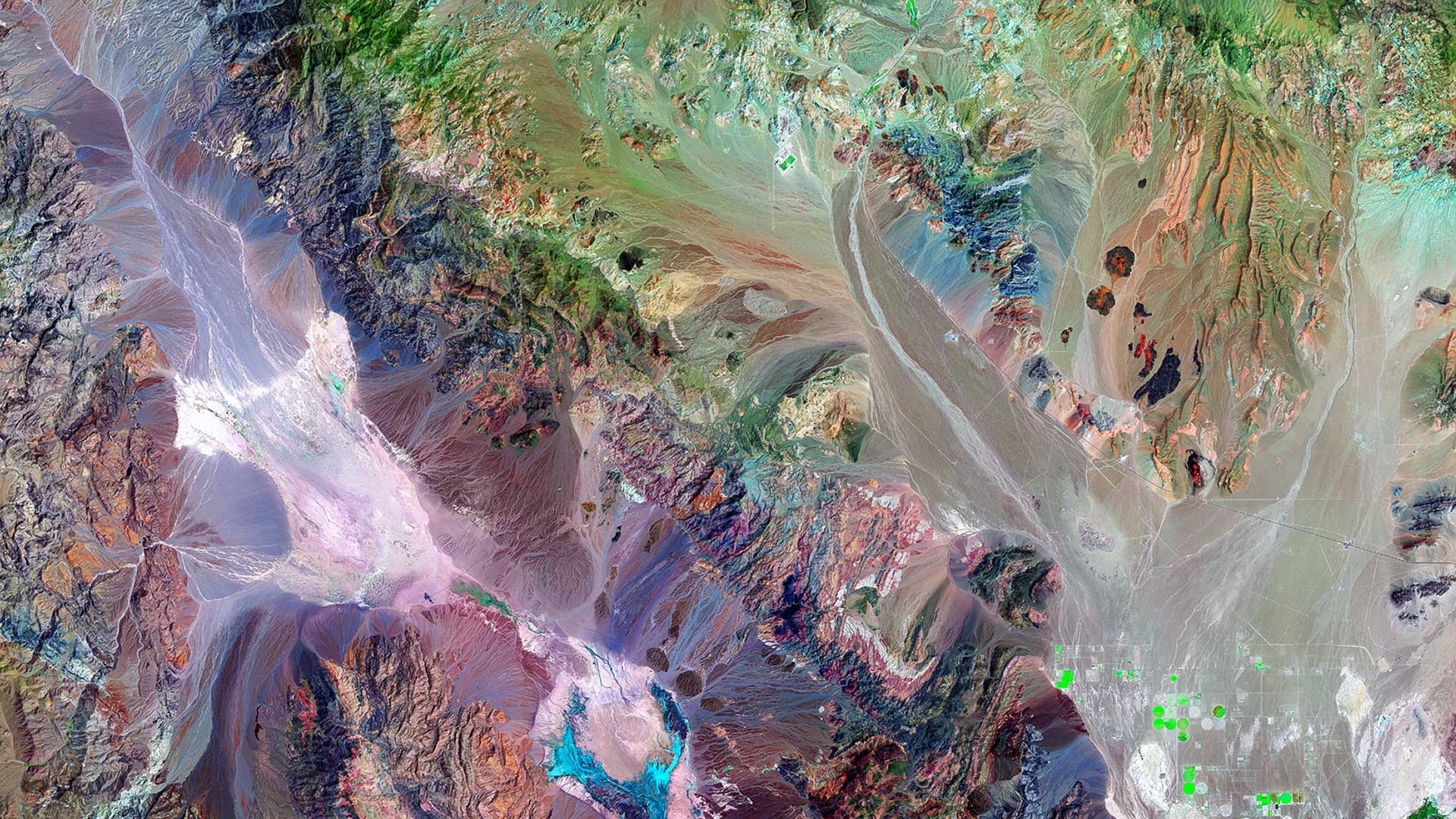

But it was colorful Landsat imagery—which, as a Hunter College student, Avila saw in an Introduction to Geography class—that first captured his attention and altered his career path forever.

“I was thinking of going to medical school,” said Avila, director, Commercial GEOINT Discovery & Assessments Office at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA). “I started working in the [college’s] microbiology lab. A year into it, it wasn’t as interesting [as I expected]. Then I took that geography class and that sparked a different interest. In a way, Landsat is art. Just how beautiful the imagery was and how colorful it was—all of that attracted me to it.”

So rather than study the science of medicine, Avila opted to study geography, photo interpretation, remote sensing, and related sciences while working on imagery-related research projects at Hunter College with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), and the US Army Corps of Engineers. He enjoyed analyzing imagery to see what others couldn’t easily see. “Slowly the interest in imagery evolved into, ‘Hey, maybe there is a career out of this,'” Avila said. He holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in geography.

After joining the intelligence community (IC) in 1987 as an imagery scientist, Avila rose through the ranks to become a national geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) officer in imagery science and then a senior scientist with NGA’s Office of Sciences and Methodologies. He assumed his current role—leading the office that assesses and acquires commercial GEOINT products—in 2018.

Esri ArcWatch editor Carla Wheeler spoke with Avila at the Imagery Summit @Esri UC last summer in San Diego, California, where he was the keynote speaker. During that address, he stressed the importance of investing in the people at the NGA, giving them the advanced technology they need, and shifting toward service-enabled analytics.

“In the future, service-enabled data streams will support analysts to look beyond just images, to search for and discover the context of complex problems,” Avila said.

Wheeler: What has been the biggest change you’ve seen in your field over the last three decades?

Avila: One is the additional amount of satellite imagery available that we can use. Certainly, over the last five to seven years, [it has been] the move from manual analysis—we used to [call it] “putting eyeballs on imagery,” [meaning] the human trying to infer what activities are unfolding in the imagery—to now start looking at how we can best use machines and automation to start doing that kind of thing.

Wheeler: Is that being done a lot at the NGA, or are you just starting out in artificial intelligence [AI], deep learning, and machine learning?

Avila: We have pilot [programs] where we are looking at how we can best use that kind of technology and what applications seem good to apply that kind of technology. We are working quite a bit with industry to see what applications they have [and] what technology they’ve developed. Part of my job in my current role is [finding out], how do we bring some of those technologies to bear on the missions sets that we are supporting? Why invent it if somebody else has done it? Take advantage of innovation that going on outside [the NGA].

Wheeler: Could AI replace or reduce the need for imagery analysts?

Avila: No. As I mentioned in my talk, there’s a cultural change [occurring]. Part of that is the evolution of how we do imagery analysis today. It’s not so much replacing a human with a machine [as] it’s, more so, changing what the human—the analyst—should be focusing on. There are a lot of repetitive tasks that an analyst does, and it eats up a lot of their time. So can we [use] machines and automation to do those repetitive tasks faster and at a larger scale, and allow the human analysts to do the cognitive and more complex tasks, which the human does better than the machine.

Wheeler: Give me some examples of what kind of things machines could do.

Avila: There’s object detection. I think technology has gotten today to the point where we can train algorithms to identify cars in a parking lot. We may need to monitor patterns of life, and we may need to look at volume of traffic or volume of cars in a parking lot. So instead of having a human—day in and day out—count how many cars are in a parking lot, a machine can do that much faster and, with the volume of imagery that we now have, can keep up with that workflow. Now the analyst can spend time trying to make sense of [the question], “What does it mean if there are 20 cars as opposed to 100 cars?”—more the contextual aspect [of analysis].

Wheeler: Could analysts also spend more time focusing on training or improving deep learning models?

Avila: In some cases, yes. Part of their workflow could be that. We may have one group, data scientists, do the training of the model initially, but in some cases we may have the analyst help validate or improve the algorithm. Initially, we can get the algorithm to a certain accuracy level, but then we can continuously try to improve and increase the accuracy.

Wheeler: Would this help save money, improve efficiency, and increase national security?

Avila: All of the above. We could be more efficient in how we use imagery and how we use our data sources. We can be more efficient in the information we derive. And we could also use our analysts in a more efficient and effective way.

Wheeler: What is the role of the Discovery & Assessments Office, which you lead at the NGA?

Avila: The Discovery & Assessments Office was established in October 2018, bringing together, into one location, work that was being done that focused on commercial solutions and market research. There’s a lot of innovation going on out in academia and in industry. Many market sectors have evolved that are making use of what we traditionally call geospatial intelligence (GEOINT). Why reinvent the wheel when somebody has already done something that we can apply in the way it was developed or, [with] minor tweaking or modification, it can better suit our mission needs?

Wheeler: What do you look for in a commercial solution?

Avila: Starting from square one, I see ourselves as a matchmaker. Understanding the mission needs that we are trying to address, we go out and look for the solutions in industry that can satisfy those mission needs. Then we start screening those solutions. Beyond knowing what their capabilities are, we need to know how accurate they are and what are the limitations of the solution. Selected commercial capabilities are brought into our environment to [let us] assess them to see if they will meet our mission needs. We need to determine the accuracy of the data and the limitations of the applications because many times they may have been tailored for a specific market sector and we may be trying to use it for something totally different. We also [ask], “How challenging is it going to be to integrate that solution into our production and analytical environment?” We have to bring those solutions into our environment where the analysts are working and integrate that data source or that imagery source in with everything else that we use. Then we also look at company viability. We would hate to start buying a solution from a company that may not be around in a year or two years.

Wheeler: What types of commercial solutions are you looking for?

Avila: We are looking at the gamut, including imagery sources and analytics products. We keep a pulse on where industry is going and what are the new companies that are evolving, especially in the small satellite [smallsat] market. We have quite a number of new entrants into that business sector. At a minimum, we want to understand who the players are and what do they bring to the table. Is it a new modality? Is it hyperspectral [imagery]? Is it a new synthetic aperture radar [SAR] vendor? Is it somebody who is looking at automatic identification system [AIS] technology] or radio frequency [RF] detections–what we consider nontraditional sources that differ from what we’ve used in the past. The interesting part of [working in] my office is, we get a chance to peek and see what’s going on in all the emerging technologies. We get a chance to speak to all these members of industry and, in some cases, influence a bit where the technology is going to better meet our mission needs. We are not only doing this for NGA . . . but it’s on behalf of our [GEOINT] community—intelligence, the Department of Defense [DoD], and the federal sector.

Wheeler: During your keynote speech, you mentioned that you were interested in advances in hyperspectral imagery. What is hyperspectral imagery, and why is it important as an emerging technology?

Avila: When you look at earth observation, think of it as a camera. You may have different cameras that look at an image—at a picture—each from a different perspective. Panchromatic was black and white; multispectral starts seeing color of an object, and that brings a new, different dimension. SAR [technology] can see through clouds and see at night. Hyperspectral [imagery] allows us to discriminate and identify material composition. Much like every human has a different fingerprint, every material on earth has a different fingerprint. Hyperspectral imagery allows you to detect, “What is that fingerprint?” It tells you this is material x [and] this is material y. Colorwise, they may look the same, but when you start looking at that other dimension, the hyperspectral dimension, now you can tell that the two materials are different.

Wheeler: What are some examples of how this can be used?

Avila: The oil and gas exploration industry may want to determine where [to] drill based on the materials they are looking for. Hyperspectral imagery could be one technology they could use to determine the composition of the materials in the landscape. In agriculture, you may be able to tell what the different types of crops in farmlands are, based on hyperspectral imagery. In national security, it’s determining the types of materials [found]. It’s one other data point we can add into our analysis and say, “Maybe these materials are different than the ones that were here last week or last month. What is the meaning of that?”

Wheeler: Turning to GIS, what type of geospatial solutions do you look for, or would you like to see?

Avila: Since I am a more of an imagery person, from my perspective it would be tighter integration and more seamless integration with what has traditionally been GIS data—your vectors and points—with AI-derived analytics. It’s bringing all that information under one source and [having] GIS help us make better sense of all that information. I saw examples of that this morning [at the Imagery Summit @ Esri UC], where all that technology is going. The AI and machine learning capabilities are being added [to GIS] . . . it’s bringing it all under one platform. I think that’s really exciting.

Wheeler: What are the most significant demands and requirements of your customers?

Avila: It’s always going to be speed of information. Many times when we get a task, when we need to provide answers to something, it’s, “I need it yesterday!” It’s how quickly we can answer the questions that we are getting asked. In some cases, it’s being able to predict: What are the questions we are going to be asked and ensure that we have the right information to be able to answer those questions quickly. With all the data that we are getting, with all of the types of analysis that we are able to do—time-series analysis and trending analysis—in a way, it’s the next evolution. Knowing what has happened in the past and what patterns we’ve seen, we can predict what may happen in the future.

Wheeler: Do you see more emphasis on predictive analytics right now?

Avila: In the research arena, there’s emphasis put on going down that route. It’s all [being] fueled by the amount of data we have access to today and the kinds of algorithms that are being developed, where we can now start seeing trends and patterns and information that lead us then to that predictive analysis. The next step is operationalizing all that activity into platforms like ArcGIS. Esri as a company is realizing that is where [it needs] to go. It’s great to see emphasis has been put on that type of development of predictive analytics.

Wheeler: In your roles at the NGA, you’ve promoted geospatial technologies and image sciences to young people. How do you get them interested in working for the NGA when there is competition from private industry?

Avila: At the NGA, the challenges we try to address are challenges you will not find anywhere else. Looking [from] the image science perspective, it’s not the type of job where you are doing the same thing every day. As an image scientist, one day I’m working with an analyst, understanding the mission need that they are trying to address. And then I look at what data sources that I have that can inform the question the analyst is trying to address. On another day, I might be working with our industry partners—a Maxar or a Planet or an Esri—to look at how can the solutions that they provide—be it imagery sources or software—better help us address our mission. On another day, I could be working with our NGA college, helping train our analysts.

Wheeler: I heard that one of your earliest assignments after joining the IC was to study the imagery in the aftermath of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster in the former Soviet Union. What was that like?

Avila: It was interesting. I was coming in fresh out of school and that was one of the first projects I was given. This was a few months after the incident had happened, and it was basically, “What can you tell us [about] what is happening there from the imagery sources that we have?” In some cases, visually some of the damage was not evident because it was only a few months after the nuclear explosion had happened. But also [we asked], “How much can we start inferring about what is the damage to come, [based] on the imagery sources that we [have]?” At the time, Landsat was one of the imagery sources. It was a good project to cut my teeth on.

To learn more about a day in the life of an NGA spectral imagery scientist, watch this video.