The Apollo 11 moon landing in July 1969 was televised live, but the black-and-white images beamed back to Earth looked grainy.

In contrast, the photographs astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin took of the rocks, craters, and powdery soil were sharp and revealing. They captured the sights surrounding them in the Sea of Tranquility: their footprints, the lunar module Eagle, the American flag staked into the ground, and themselves moonwalking in a mix of sunlight and shadow.

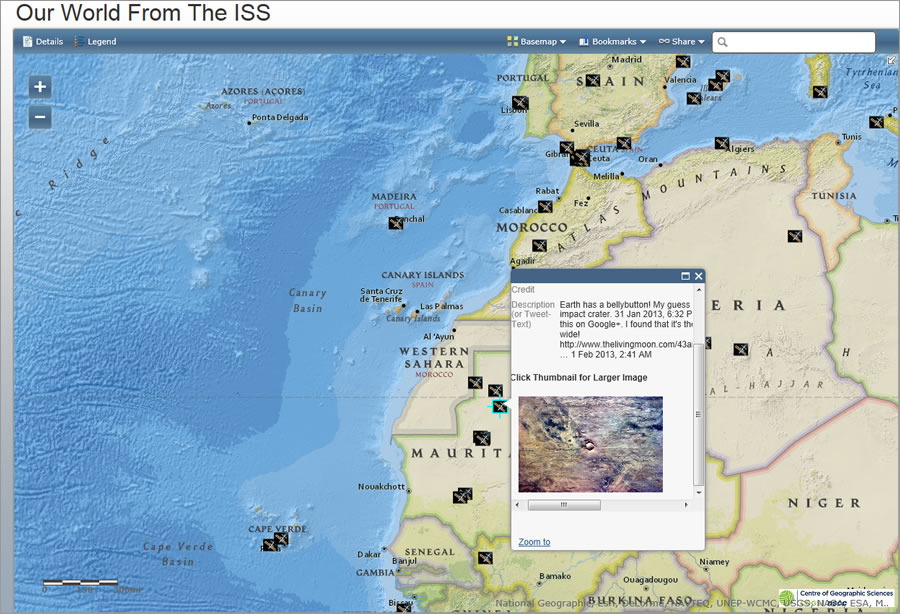

The photos, published later in newspapers, magazines, and posters, became some of the most iconic of a generation. But what if Armstrong, Aldrin, and other astronauts of yesteryear had powerful social media tools available like Twitter to communicate directly with Earthlings? It’s the medium Commander Chris Hadfield from the International Space Station (ISS) used to share photographs he took from his ISS perch such as one of a crater in Mauritania, Africa: “Earth has a bellybutton! My guess is that this perfect African circle is a meteor impact crater,” he posted with the picture.

Today social media, with doses of humor, are very much a part of the space mission, with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), and many astronauts sending messages, videos, and photos back to Earth via Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Followers post messages for the astronauts too, making interaction about space interactive.

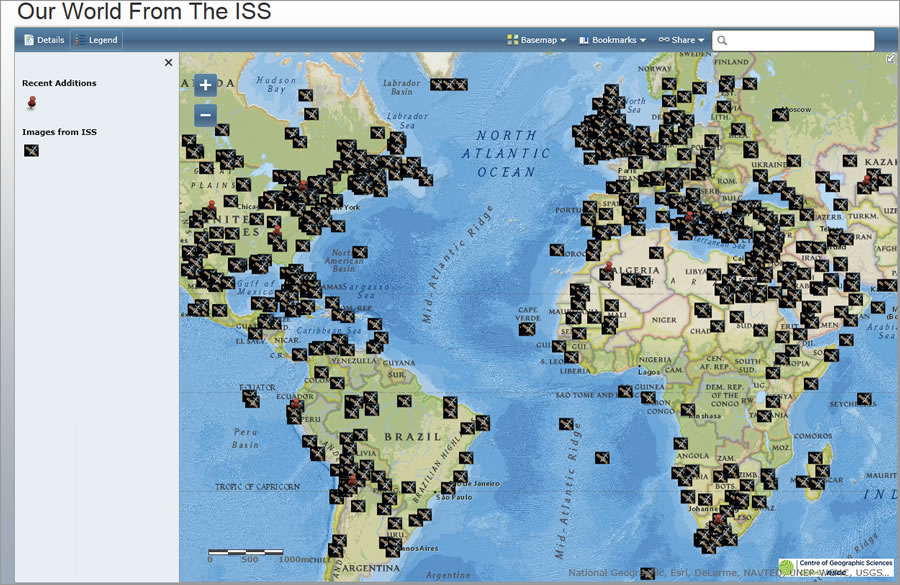

The photos Hadfield and fellow ISS astronaut Thomas Marshburn sent via Twitter inspired their follower David MacLean, a faculty member at the Centre of Geographic Sciences (COGS), Nova Scotia Community College, and his students to create a mapping app called Our World from the ISS. It used Esri ArcGIS Online to map more than 950 photographs of interesting places on Earth that Hadfield and Marshburn shot from space. They took the photos during their December 2012–May 2013 mission and posted the images on Twitter with their observations of each scene (in 140 characters or fewer, of course). Hadfield, a Canadian, was especially prolific and poetic. (Watch Hadfield sing his version of David Bowie’s song “Space Oddity” from the ISS.)

MacLean, also a Canadian, was intrigued by the astronauts’ unique perspective as they orbited 400 kilometers (250 miles) above earth, photographing everything from cities to barrier reefs and sand formations to smoke from brush fires. He didn’t want their geologically and geographically interesting images and descriptions—such as “taffy-twisted African rock” and the “yin and yang of ice and land”—to quickly get swallowed and lost in the fast-moving Twitterverse.

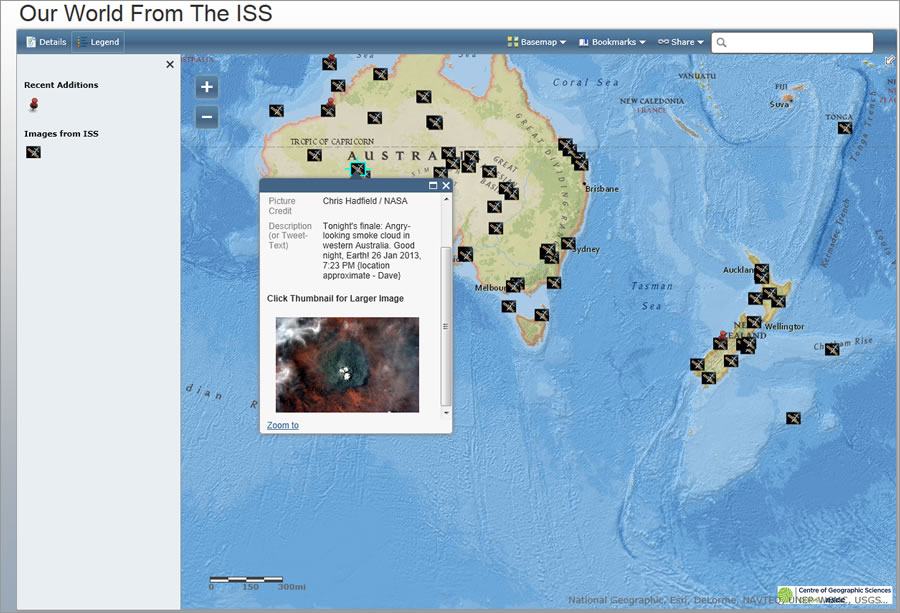

“[Hadfield] took pictures all over the earth, with wonderful prose as he described the outback of Australia and parts of Mauritania and Algeria that no one would [otherwise] get to see,” MacLean said. “Unfortunately, Twitter seems to be a very temporal medium, and all these wonderful pictures—these rich resources—slip away and you have to really look to find them.”

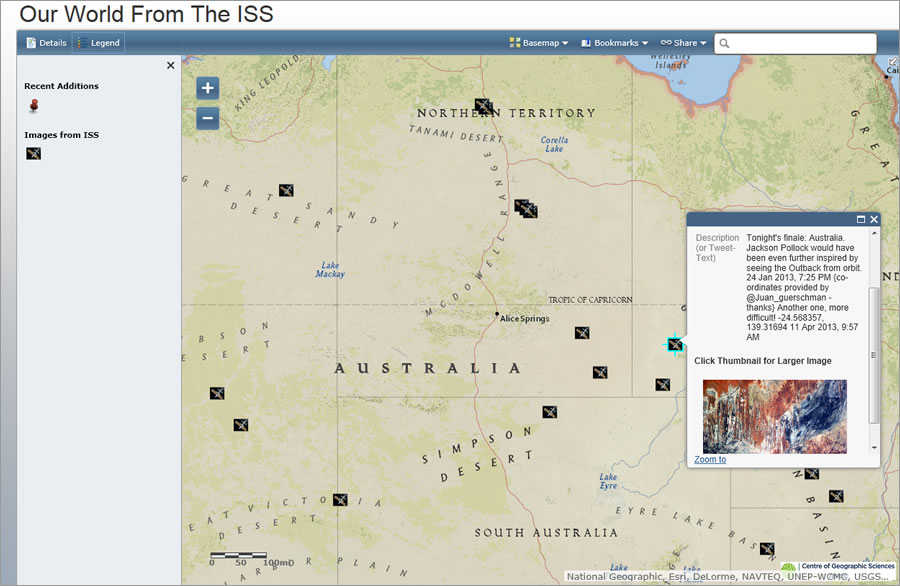

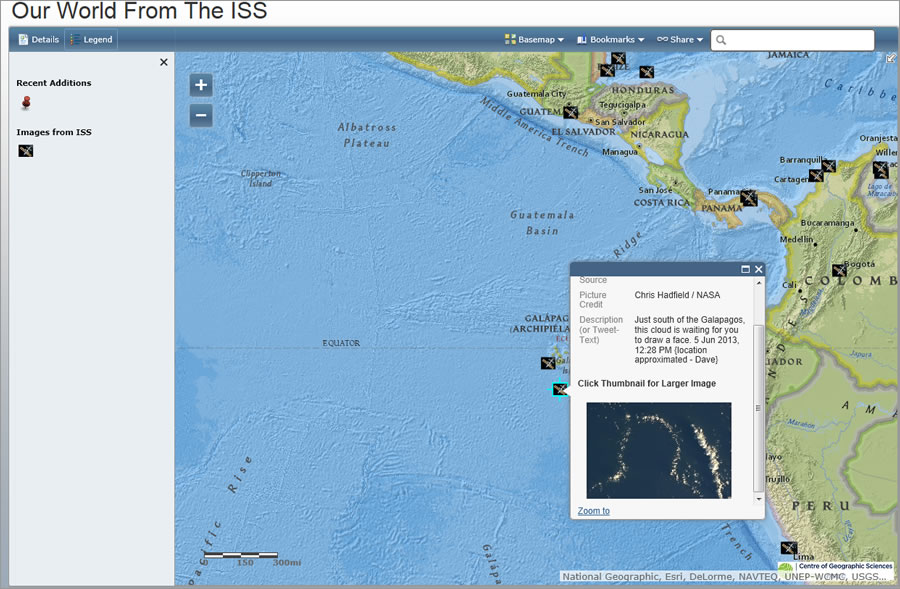

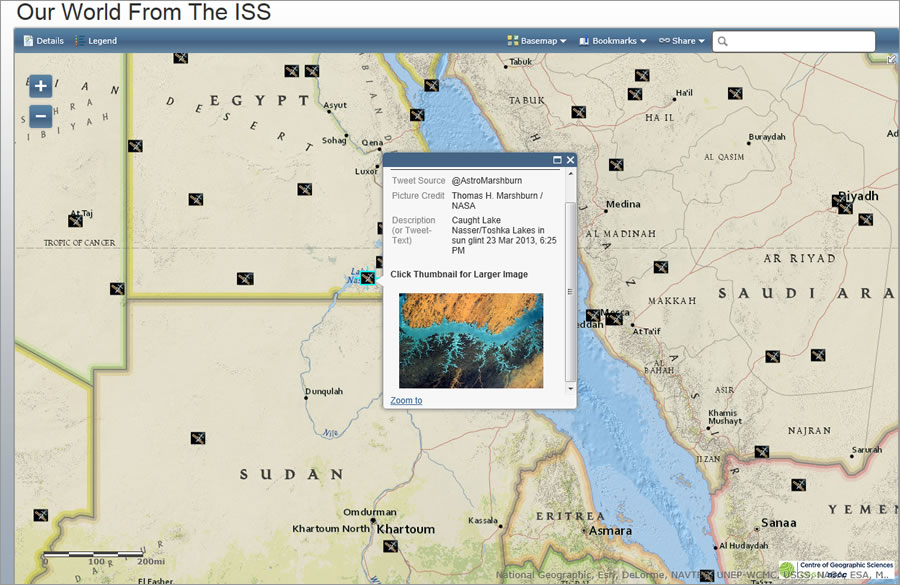

MacLean wondered if there was a way to preserve the images and messages in the Tweets in a form that was easy for people to find and view. He decided to try building a mapping app, which he and his students created using geographic information system (GIS) technology from Esri, online comma-separated value (CSV) files, and Google Docs spreadsheets in Google Drive. Their map displays icons, provided courtesy of the Canadian Space Agency, that look like small space stations. These show the approximate (or, at times, quite accurate) locations of each photograph. Viewers can pan the map, zoom in to any area of interest, and tap an icon. A pop-up window will appear that includes a thumbnail of the picture and the message from the astronaut. You can also click the thumbnail to see the full-size Tweet in the astronauts’ Twitter feed. (Clicking the photo in Twitter will then bring up a larger, sharper image.) It’s a little like seeing photos of landscapes in National Geographic—only taken from space.

Tap an icon north of Medina, Saudi Arabia, to see Hadfield’s May 3 photo of the Harrat Khaybar volcanic lava field and read his post: “The Earth bubbled and spat, like boiling porridge, long ago in Saudi Arabia.” Another geologic wonder caught his eye Down Under: “A splash of dry salt, white on seared red, in Australia’s agonizingly beautiful Outback.”

Preparing and presenting the images and Tweets in a mapping app was a simple, straightforward process and a wonderful way to show students how to use ArcGIS Online, according to MacLean. “It was a lot of fun,” he said. “The students in our Advanced GIS class for the Advanced Diploma in Geographic Sciences program got to be involved. Many of them helped to populate that database as Tweets came through daily.”

MacLean and the students monitored Hadfield’s and Marshburn’s Twitter feeds. As the messages and photos appeared, they used a Google form to populate a spreadsheet with the URL of the Tweet, the Tweet’s text and source, and the latitude and longitude of someplace in the photo. On certain Tweets, information about the location was added to the text to help viewers gain perspective for those Tweets. Google automatically published the spreadsheet as a CSV file (which is consumed by the ArcGIS Online Map app each time someone opens or refreshes the map). The app displays the CSV information in a pop-up window.

The Details section of the app explains the process for creating it, the underlying technologies that were used, and the permissions MacLean sought and received. Information is also included about the Nikon cameras that Hadfield and Marshburn used to shoot their pictures.

MacLean said the map has been viewed more than 150,000 times by people in more than 80 countries. The number of hits rose tremendously after Hadfield and his son, Evan, Tweeted the map to their 1 million followers in mid-March.

Though some of the most striking photos depicted unusual rock formations, sand dunes, cloud vortexes, volcanoes, sunrises, and sunsets, sometimes the photos and Tweets were related to the news. Shortly after the National Hockey League (NHL) lockout ended in January 2013, Hadfield shot pictures of some of the teams’ cities. “Montreal, you’re shining bright, it must be @hockeynight in Canada!” he said, attaching an image of the city enveloped in a golden glow.

“When the meteor went over Russia [in February 2013], [Hadfield] very quickly had pictures of meteor hits on earth in other parts of the world that have occurred over time,” MacLean said. “So with lovely, timely content like that, he really caught the interest of people around the world, and especially Canadians.”

Turning their cameras to earth, the astronauts found much to marvel and contemplate. They photographed cities where millions of people live in compact urban areas and captured images of natural phenomena that looked like works of art.

Hadfield also found humor in what he saw, such as a clouds formed in the shape of a person’s head and shoulders. “Just south of the Galapagos, this cloud is waiting for you to draw a face ,” he said. And he inspired his followers to observe more and perhaps, in the future, explore more. “Do you see the face in Eua Island, Tonga? I want to walk around the tiny dot island!”

The Apollo 11 moon landing in July 1969 was televised live, but the black-and-white images beamed back to Earth looked grainy.

Hadfield saw the Our World from the ISS mapping application. In June, after returning to earth, he shared his impressions of the app as “Coalescing a number of thought and image fragments collected over many months. [It] organizes them into a manner that shares the fragility and beauty of our one Earth.”

To learn more about the Our World from the ISS mapping app, listen to this podcast with David MacLean.

See the story map, called Canada from the International Space Station, that Esri Canada Limited built using the app’s data.

Read Using Google Docs in Your ArcGIS Online Maps, a blog by Esri technical evangelist Bern Szukalski.