An urban design competition focused on turning an area that had heavy industrial and extensive transportation infrastructure development into a vibrant neighborhood that would restore the connectivity of its historic past, ensure its climate resilience, and preserve it as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Prague, one of Europe’s fastest-growing cities, faces an ongoing struggle to reconcile dynamism and preservation. Urban development trends in the Czech Republic’s capital evince a clear desire to return to a city that is more accessible to pedestrians—not for the sake of nostalgia, but because it will improve the city’s livability.

Much of this activity is occurring in brownfields that were once home to rail terminals and other transportation infrastructure. One of the largest brownfields is Florenc. Near the historic center of Prague, it is a neighborhood on the edge of New Town, which was established in the 14th century.

Prague’s Institute of Planning and Development (IPR Prague), a public benefit corporation that is the main policy making unit for urban architecture, planning, development, design, and administration for the city, employs a digital twin of Prague that lives in the city’s GIS. Planners use the digital twin to design outcomes that are then tested.

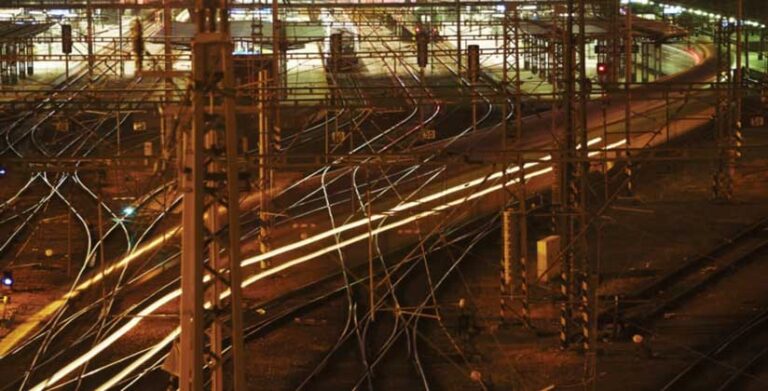

Many planning projects focus on reducing the rift that was created by the city’s main rail lines nearly 200 years ago. Rail lines destroyed surface connections between neighborhoods while opening connections to the rest of Europe.

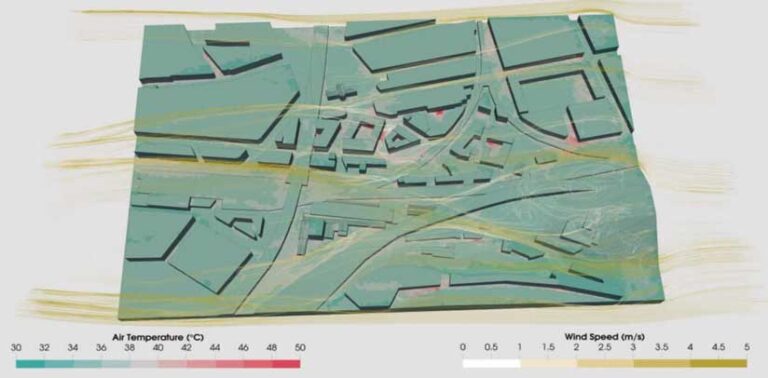

In recent years, IPR Prague has taken a special interest in determining how climate change will affect and alter the city. The city’s digital twin helps new development strike the right balance between efforts to address climate pressures and changes that improve the lives of residents. Using GIS, city planners have constructed 3D models of Prague’s microclimates. These models provide a way to simulate the effect of mitigation strategies before they are implemented.

The Future of Florenc

The modern character of Florenc was formed half a millennium after the founding of New Town when rail disrupted the old patterns of the city. “It’s basically a 19th-century development, an old industrial and residential quarter,” said Jiří Čtyroký, IPR Prague’s director of spatial information.

Čtyroký noted that Florenc is one of Prague’s largest brownfields. It’s a contaminated remnant of the area’s industrial past and evidence of the modern transportation infrastructure that now dominates the locale. A nest of rail lines; a large bus station; a major subway transfer point; a clogged arterial road; and the Negrelli Viaduct, which carries trains over the Vltava River, have made Florenc less a neighborhood to live in and more a place to travel through.

Over the next few years, the Florenc brownfield will be replaced with housing for 1,600 new residents and business development that will create 3,200 job opportunities. IPR Prague models show that this development risks creating heat islands and intense warming in Florenc.

“That’s exactly the kind of place where it’s worth implementing the microclimate modeling, because it’s a place where massive change will occur, and we want to see how it will work,” Čtyroký said.

International Teams Ponder Florenc’s Future

Last year, IPR Prague helped organize Florenc 21, an architectural competition that attracted 57 teams of architects and urban designers from around the world. Each team submitted ideas for how to reorient Florenc around the coming changes.

“We thought about creating a physical model of the competition area, where all participants could input physical models of their proposals,” said Luboš Križan, an urban planner with IPR Prague’s Office of Territorial Support. “But it would’ve been extremely expensive and complicated for us to make the whole model available to all five competitors, and it would take a lot of time to do so.”

“So, we thought, Why not use a digital twin and web app to share the model of the neighborhood?” Čtyroký said. “It would be cheaper and more flexible.”

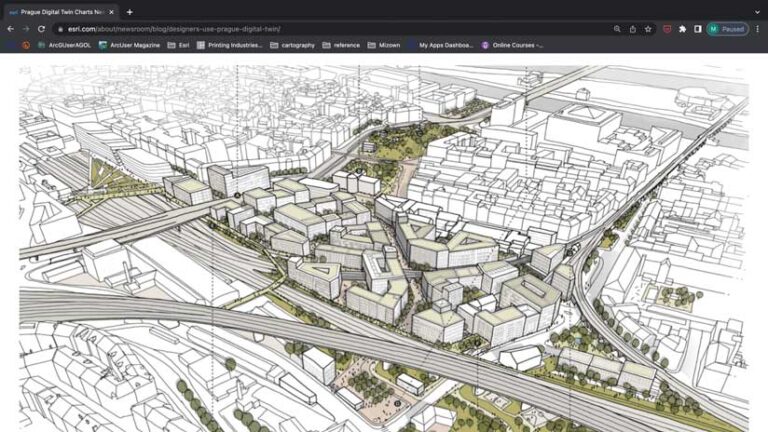

Sam Blanár, an IPR Prague developer, pulled the 3D model for Florenc, and used GIS to create an app that all participants could explore. Using the app, the finalists were able to blend their plans into the digital twin. The five contest finalists developed their designs into overall plans and received access to IPR Prague’s digital twin of the city to use for their presentations.

In the past, Čtyroký explained, IPR Prague would sometimes augment finalized design proposals by asking the winning bidder for data. “Then we’d put it into the digital twin,” he said. “But this was the first time the 3D model was used in real decision-making during a competition.”

This provided a standardized view that enabled the Florenc 21 judges to compare the entries. It also allowed them to make informed judgments about massing [an architectural term that describes how a building design fits into its surroundings] with a level of detail not possible with either standard two-dimensional plans and images or visualizations that are aesthetically pleasing but contain little useful information.

The winning proposal came from Team 24, composed of UNIT architekti, A69–architekti, and Marko&Placemakers. Filip Tittl of UNIT architekti described the unique infrastructural and topographical constraints that made reimagining Florenc a challenge: the arterial road, railway bridge, subway tunnels, rights-of-way for future subway lines, and land that rises as one moves away from the riverbank. “All of this creates one of the most complex places in Central Europe,” Tittl said.

Climate and Connectivity

In keeping with IPR Prague’s interest in how Florenc will fare in an era of climate change, the winning team integrated sustainable energy sources and microclimate research into its design. Vegetation is strategically placed to mitigate heat islands, and a ventilated street design should maximize the cooling effect of the predominant winds.

Climate change is not the only issue that affects the rethinking around Florenc. The process also reflects a return to certain values that were once basic to how people thought about cities.

New Town existed for 500 years before the establishment of the Masaryk train station brought rail transit to Prague. The station cut off Florenc from New Town and began the area’s shift away from an intimate neighborhood in which everything residents needed was within walking distance to an area oriented around mechanized travel and industry.

The result was a region of diminished connectivity. Walkability and pedestrian flows were increasingly narrowed and blocked. A major renovation of the Masaryk station, that began as part of another urban architecture competition in 2009, has sought to restore that connectivity.

The Florenc 21 website noted that, “At the time of its establishment, the station was proof of the modernization of the city and its economic progress.” However, the winning proposal works with the demands of the 21st century for jobs in new economy sectors, strategically locating the transport hub, and supporting pedestrian links.

Among the changes to improve connectivity is the reestablishment of pedestrian and cycling interconnections among three major streets that the station once blocked. Gardens that were once replaced by tracks have reemerged as part of the station’s roofing.

Florenc 21 has further refined the values of connectivity and livability so that Florenc the transport hub is now subsumed into Florenc the neighborhood and is no longer an island. The winning proposal included multifunctional buildings, an urban market, and retail stalls under the viaduct’s arches. IPR Prague praised the winning team’s vision of a “highly permeable neighborhood that connects all the surrounding neighborhoods and heals the wounds left behind by the construction of transport infrastructure in Florenc.”

International Recognition

In 1992, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) designated Prague’s Historic Center, an area that includes part of Florenc, as a World Heritage Site.

When UNESCO granted the area world heritage status, it noted how the region “admirably illustrates the process of continuous urban growth from the Middle Ages to the present day.” Nearly two decades later, Prague’s post-Cold War expansion caused UNESCO to reconsider, noting in 2019 that the integrity of the area is “threatened by the pressure of developers wishing to build oversized new buildings.”

UNESCO made it clear that, should unchecked growth continue, the Historic Center could lose its world heritage status. Florenc 21 is a signal to UNESCO that the city is serious about smartly managing these development pressures.

“For the people from UNESCO and Prague’s heritage office, it’s extremely important to look at panoramic views, to see how structures would work with surroundings,” Križan said. The digital twin allowed designers to consider these values throughout the design process. UNESCO lauded the winner’s potential to better reveal the exceptional value of this part of Prague.

The web app made it easy to understand the effect a proposal would have by it displaying it realistically. Blanár preloaded perspectives of noteworthy locations in the app such as the view from the Prague Castle, which dates back to the ninth century.

“The judges could check it out using the 3D model,” he explained. “We had prechosen a few spots that showed some of the most beautiful and panoramic scenes of Prague, and there was a tool to click on them, which rotated the scene into the proper position so that everyone could look and instantly compare the spots on the proposals.”

The next step will be a feasibility study for the proposal. IPR Prague is optimistic that the plan will withstand the scrutiny. “Florenc is a scar on the city of Prague,” Ondřej Boháč, IPR Prague’s director, bluntly noted, “which will finally be healed, thanks to this competition.”