As the end of the fiscal year (FY) for 2021 approached, the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) was on track to have more than 1.1 million encounters with migrants along the US-Mexico border. The last time migrant encounters occurred at this rate was in 2006.

Although increasing numbers of people have been crossing at multiple locations along the US border with Mexico, the Rio Grande Valley in south Texas sees some of the highest crossing rates in the country. Once in the US, migrants pass through urban areas such as McAllen, Harlingen, and Brownsville along the border. As they travel north, smuggling organizations provide groups of migrants with foot guides who lead them through rugged terrain to rendezvous points where drivers pick them up and transport them to the interior of the United States.

This initial part of the journey is on foot. It often takes days, walking through south Texas ranch lands that have sandy soil and little to no shade. These conditions are difficult for experienced and well-supplied hikers, but migrants are often fatigued to begin with and carry minimal provisions. Temperatures regularly exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit. To further complicate matters, migrants are often told their journey will be no more than a few miles, instead of distances that are up to 40 miles.

Lack of experience and preparation combined with the tough pace set by guides creates a situation in which migrants are susceptible to injury or illness. Smugglers abandon injured or ill migrants and continue pushing their groups north. This complete disregard for human life by smugglers prompted the US Border Patrol (USBP) to expend considerable resources, to save the lives of hundreds of migrants in distress each year, as reported by the Department of Homeland Security.

Managing Rescue Efforts

USBP rescue efforts begin in the home countries of many migrants. USBP advises migrants who have entered the US illegally and are in distress to immediately call 9-1-1 from a mobile phone. Injured or ill migrants will often wait hours or days for their guide to return for them. When it becomes apparent that the guide is not returning, distressed migrants then call 9-1-1. Brooks and Kenedy counties in south Texas receive hundreds of such calls each year, but state and local officials do not have the staff or resources to respond to all these calls.

Consequently, USBP has taken a primary role in conducting search and rescue (SAR) operations for migrants in distress. The USBP Missing Migrant Program (MMP) is the lead unit involved in rescues of distressed migrants in the Rio Grande Valley. SAR events often involve multiple offices and assets both in the field and at headquarters. In the Rio Grande Valley, rescue partners include local 9-1-1 dispatch, USBP agents in the field, USBP agents at the Rio Grande Valley Sector headquarters, special operations personnel, and Air and Marine Operations (AMO).

Managing these events is a complex task with time being the crucial component. Time can mean the difference between life and death for migrants. When a rescue event is initiated, it typically begins at a local 9-1-1 dispatch center. A person in distress dials 9-1-1 for emergency assistance. Once the caller is identified as a migrant, operators transfer the call to USBP. The migrant’s location is reported as either phase 1 or 2, which determines the method used to identify the mobile phone’s location and the relative reliability of that location. USBP has documented errors of up to 40 miles for phase 1 and up to 4 miles for phase 2.

Coordinating Response

Proximity to Mexico means many of the emergency calls are received by C4, Mexico’s emergency services. Currently, C4 does not have the capability to provide coordinates to USBP. In addition, no standard operating procedures were in place for call transfer, so different USBP offices—local stations, dispatch centers, and sector headquarters—received emergency calls.

Responding offices assuming the primary role for the SAR operation often had their own procedures. USBP personnel asked questions based on local protocols, wrote information down on paper, or entered it digitally, and followed procedures with minimal guidance.

SAR partners became involved in these events through phone calls and emails requesting support. Agencies providing support were often responding based on information that was thirdhand or even farther removed from its source and could provide an incomplete view of the event. There was potential for critical information to be overlooked or lost. After looking at event response, MMP identified three specific issues:

- Information collected for SAR events was not standardized or prioritized, which made communication among rescue partners complex and often gave rescue personnel incomplete information.

- Migrant distress calls frequently occurred in areas with minimal cellular signal, so location accuracy was unreliable.

- Overall situational awareness of SAR events was poor, and communication among SAR partners and assets was inefficient.

Improving Response

To address these issues, MMP collaborated with the author, who is the USBP Sector Intelligence Unit Cartographer (SIU-C). As a specialist in GIS who is highly proficient with Esri software, the author reviewed MMP requirements and recommended the CBP Portal as the optimal resource for a new SAR system. The CBP Portal is built on ArcGIS Enterprise. Information can be managed within the CBP Portal and displayed in a variety of formats tailored to USBP SAR requirements and accessible to all CBP staff. Such a system could improve communication among rescue assets, assist SAR coordination, enhance location identification and verification, and provide a comprehensive overview of events.

At the end of FY 2019, the author deployed a new portal-based SAR system for the Rio Grande Valley using CBP Portal. The system addresses each concern identified by MMP and consists of three primary components: GeoForm, ArcGIS Web AppBuilder, and ArcGIS Dashboards. These components are nested within a tabbed ArcGIS StoryMaps story, making the SAR system readily accessible. The system was designed to provide a single-tab solution for each of the three concerns outlined by MMP.

When initially opening the story, the first tab opens a Portal for ArcGIS GeoForm. This is a web-based data entry form with an imbedded map. The map is preloaded with critical information to assist data entry personnel in identifying and verifying the location before data submission. The GeoForm was built with a series of open text fields for descriptive information, and drop-down options based on domains are available for select fields in the target feature layer.

By utilizing prebuilt entry fields, data is standardized. This addresses the first concern MMP raised in its initial assessment of USBP SAR operations. Fields are arranged to collect high-priority information first—phone number, phone battery level, and the caller’s well-being. This increases the effectiveness of initial data collection in case the call is disconnected before the GeoForm can be completed or if the battery level is sufficiently low that the agent responding to the call needs to quickly submit the GeoForm to initiate SAR operations right away.

This data triage ensures SAR operations can begin with the minimum necessary information. Further down the form, information captured is designed to assist SAR personnel in identifying and verifying the location of the caller. This also entails getting a description of the immediate area and any unique features that may stand out—especially from the air. These could be natural features, such as lakes and rivers; built features, such as buildings and roads; landmark features, such as electric transformers or windmills; or USBP location markers.

To aid in locating migrants and address errors in their initial location, the author and MMP created the location matrix (LM). Migrants may have reported being near one of these features but had no way to uniquely identify them, so USBP couldn’t locate them. LM is a series of points of known features, found throughout the Rio Grande Valley, that have unique identifiers. MMP contacted local infrastructure managers and landowners and requested GPS locations for these features.

The author compiled the information and standardized the data into a single feature layer. MMP enhanced LM by adding its own features such as location signs and rescue beacons. LM features, which have unique ID numbers, are placed in areas where public and private infrastructure is sparse.

Currently, USBP has more than 1,200 LM features in the Rio Grande Valley, with more scheduled for deployment soon. LM features were added to an interactive mapping application built with ArcGIS Web AppBuilder and included on tab 2 of the SAR system.

ArcGIS Web AppBuilder provides a tool that facilitates a search of records based on information in a target field of a feature layer. In this case, the target field contains the unique LM ID assigned to each LM feature. Migrants read the ID to USBP personnel, who enter it in the app. Although markings can fade or become unreadable, the search tool can locate LM features based on a partial ID. In addition to the search, USBP personnel can use the app to update SAR records with new information, edit existing information, and export records to share with SAR partners that may not have access to the CBP Portal.

USBP rescue personnel also take advantage of the high-resolution imagery provided by Esri that is available in the app to verify the location of LM features. USBP personnel can zoom in to the location provided by a migrant to query the surrounding area. If the information provided by the migrant does not match the imagery, callers can be directed to find LM features, or USBP personnel can use traditional aerial photo interpretation skills to identify the correct location.

Once the record is complete, SAR personnel view the location right away in various command and operation centers, in the field, and at Rio Grande Valley Sector headquarters, where MMP and USBP leadership can make appropriate command decisions to conduct the rescue.

Overall Situational Awareness

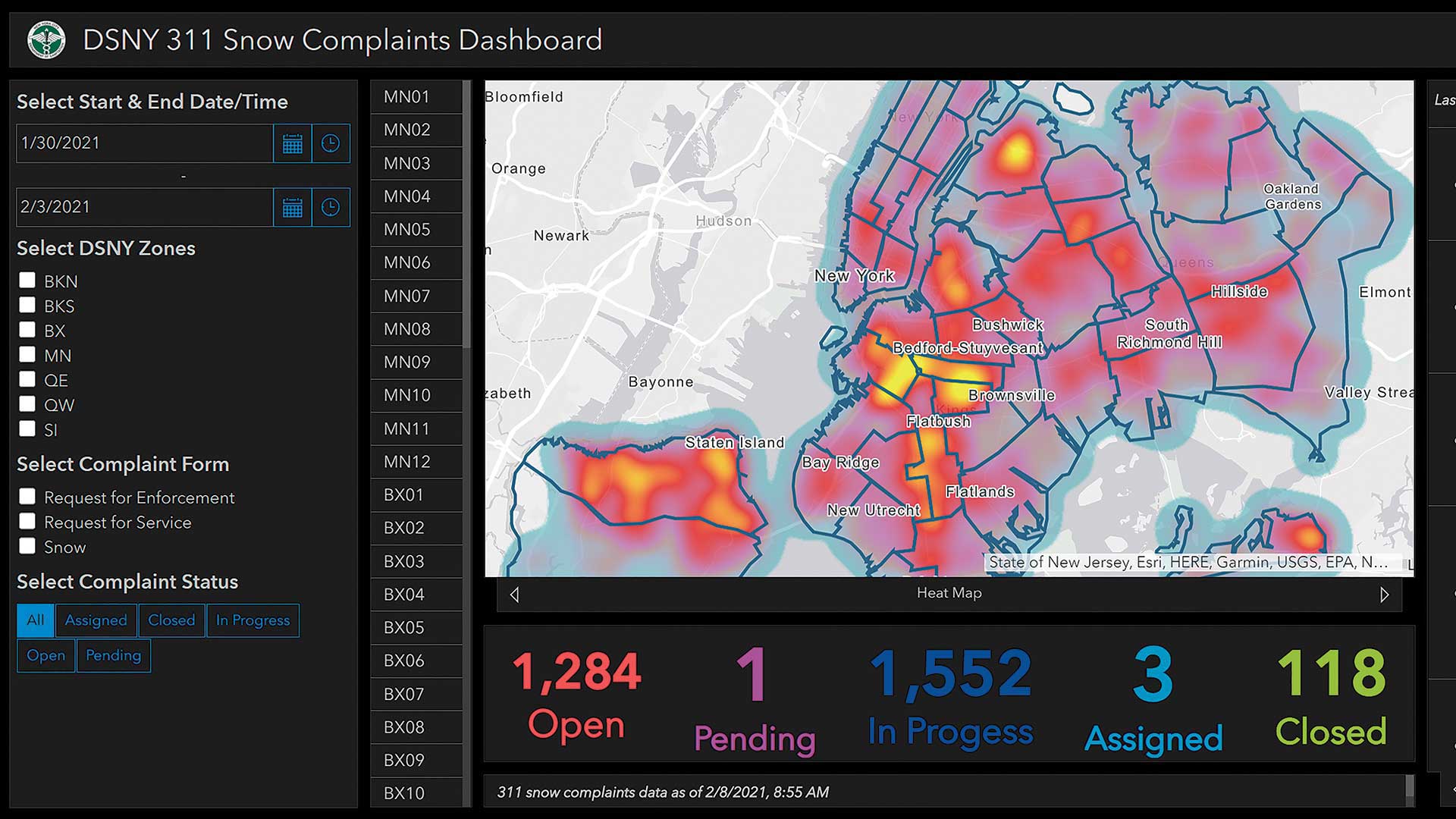

The final component of MMP’s SAR system, located on tab 3 of the ArcGIS StoryMaps story, is the information dashboard. Using ArcGIS Dashboards, the author developed an interactive situational awareness tool so SAR partners can view all active SAR events. The tool also provides all standardized call information and a comprehensive view of SAR operations conducted in the Rio Grande Valley and makes historical information and statistics readily available. This information helps USBP deploy rescue assets, track illicit organizations, and continue improving rescue efforts.

As the lead unit responsible for SAR events, MMP regularly uses the dashboard to provide visibility into its activities, respond to requests for information, and advise agency management of conditions in the Rio Grande Valley. It also provides a live view of current events, with interactive counters, filters, graphs, and other widgets that display a large amount of information concisely.

Improved Rescue Rate

SAR operations are a priority lifesaving mission at USBP. The novel SAR system based on ArcGIS Enterprise is the key component for USBP management of rescue events in the Rio Grande Valley. By standardizing and prioritizing information, improving situational awareness, and disseminating key information for decision-making and analyses, MMP maximizes rescue effectiveness.

In FY 2019, these SAR operations successfully saved slightly more than half the number of migrants in distress. After the SAR system was deployed, the rescue rate improved considerably. As of July 2021, the rescue rate in the Rio Grande Valley is almost 90 percent for the current FY. In the 24 months since the system went live, it has been used to successfully rescue more than 1,000 people. This substantial improvement of USBP SAR efforts demonstrates the power of ArcGIS Enterprise applications to provide novel solutions to critical problems. When considering the extent of the ongoing humanitarian crisis at the US-Mexico border, the benefits are clear.

For more information, contact the author, Paul B. T. Merani at 956-289-4800 or paul.b.merani@cbp.dhs.gov.