ArcGIS has pivotal role in massive exercise

On a morning in mid-June, disaster response managers were summoned to situation rooms across the South and Midwest. A grim scenario awaited them. A 7.7-magnitude earthquake, centered between Memphis, Tennessee, and St. Louis, Missouri, had unleashed unimaginable devastation from Alabama to Illinois. Given the scope of the quake, casualties likely numbered in the tens of thousands, with millions of people facing displacement.

The scene, fortunately, was fictional, a multistate disaster response exercise simulating a megaquake in the New Madrid Seismic Zone, a network of geologic faults stretching from Arkansas to Illinois. (See the accompanying article, “The New Madrid Seismic Zone.”)

Capstone-14

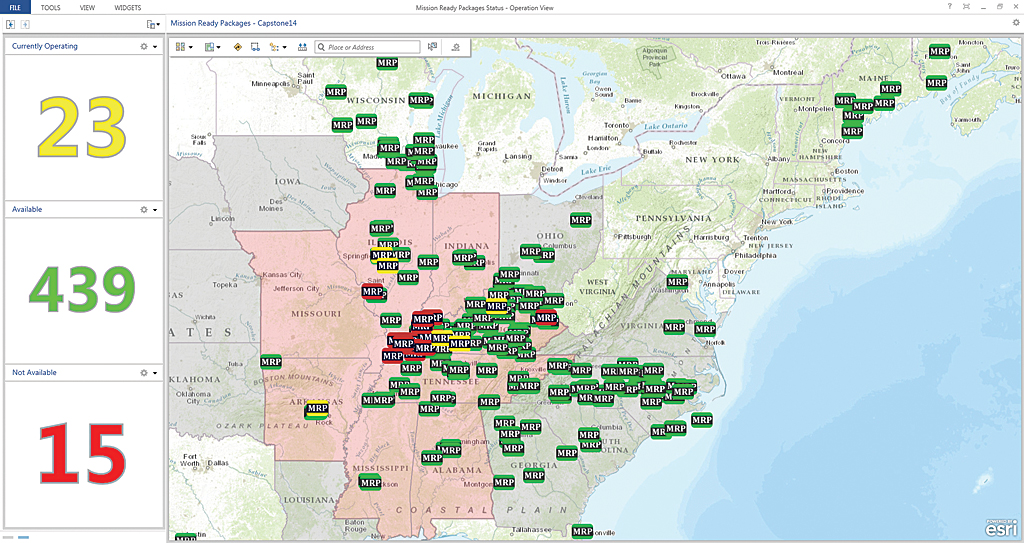

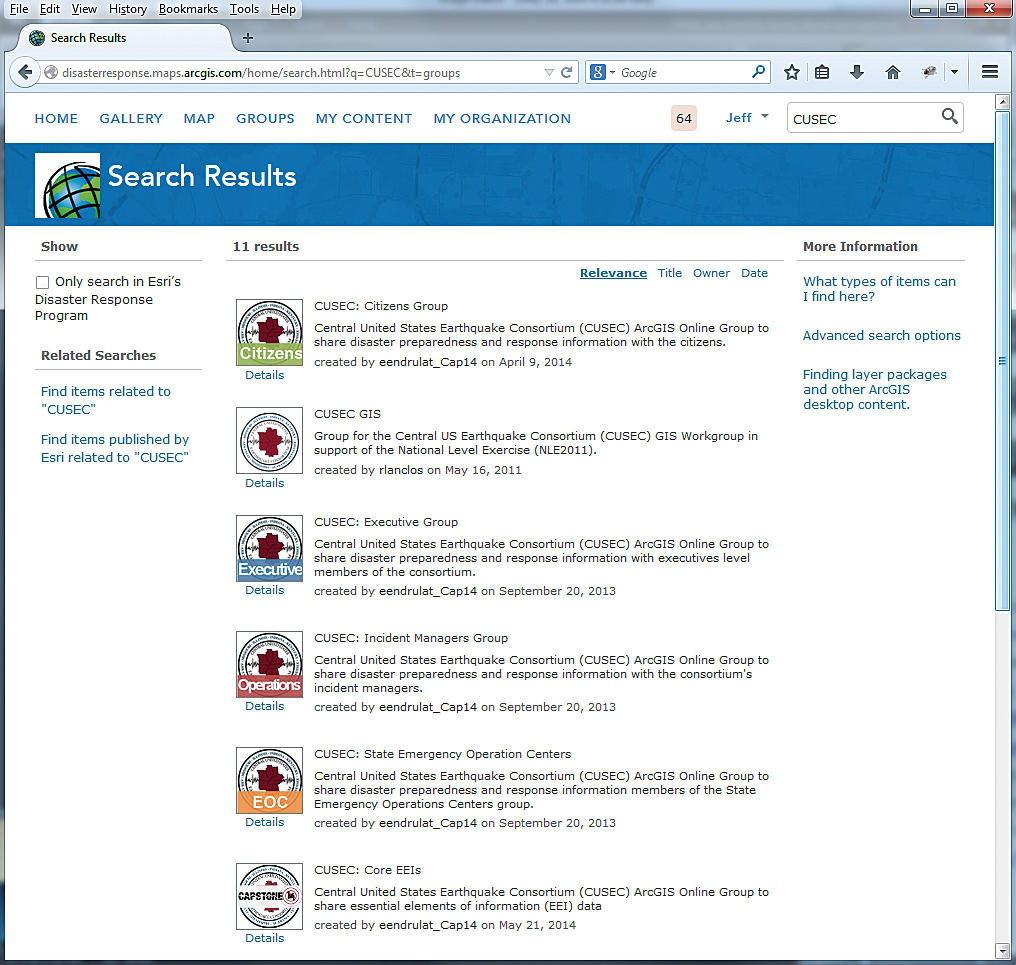

Officially known as Capstone-14, the scripted exercise, held June 16–20, 2014 was designed and directed by the Central U.S. Earthquake Consortium (CUSEC), a partnership of midwestern and southern states affected by the New Madrid fault system. Participants included state-level emergency managers in CUSEC states Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee. Modeled after a 2011 effort, the mock quake served to test states’ levels of preparedness, access to resources, and capabilities for gathering and sharing information. Esri deployed ArcGIS Online in each CUSEC state to facilitate information sharing and provide a common operating picture (COP) for agencies, emergency managers, and responders.

“In an event of that magnitude, you quickly realize you don’t have enough stuff,” said Jonathon Monken, CUSEC chairman and director of the Illinois Emergency Management Agency. “You don’t have the teams or equipment or resources to deal with the problems you’re going to have. It really comes down to how you prioritize—what goes where and who gets what. And without a system in place to share and access information, all we have are spotty field reports. ArcGIS is absolutely the essential next step in disaster response.”

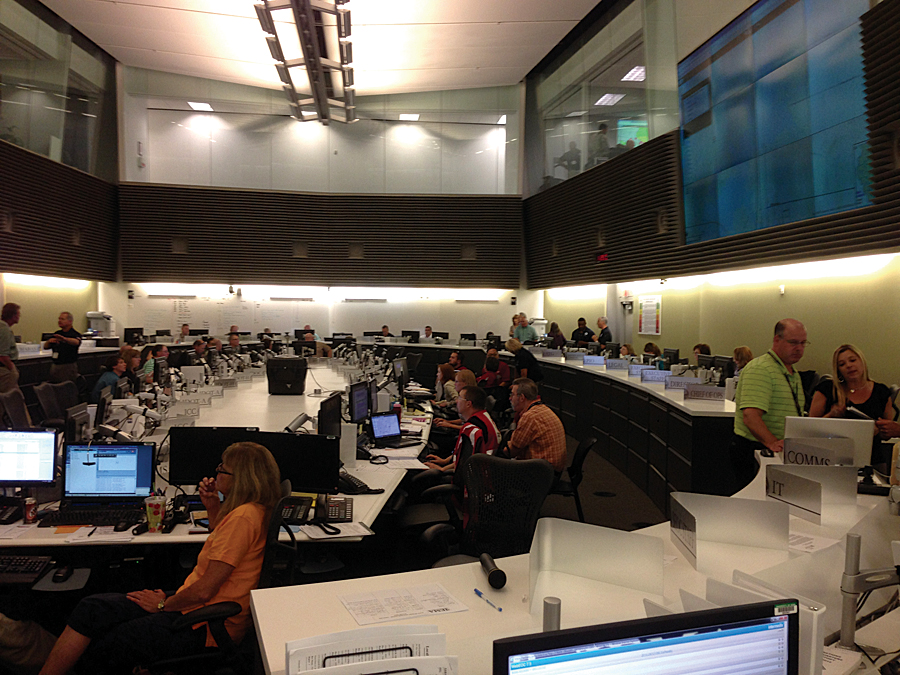

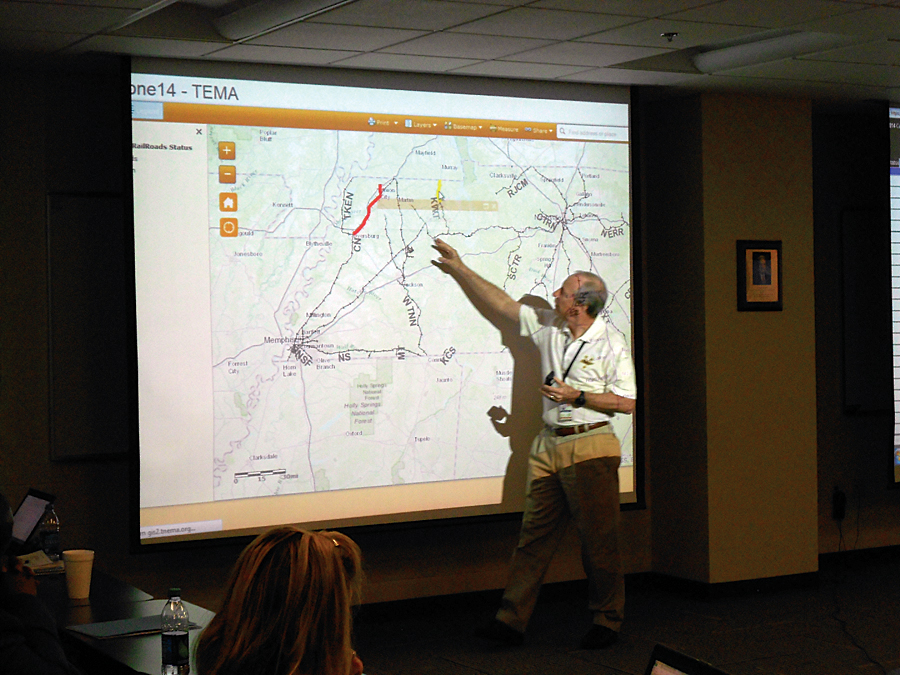

Capstone-14 could be described as eight state-specific exercises embedded in a larger regional exercise directed from the Illinois emergency operations center, in the state capital of Springfield. In each CUSEC state, emergency managers—representing a range of agencies, from the National Guard and state police to state forestry and finance departments—used Operations Dashboard for ArcGIS to monitor unfolding events and response efforts.

Initially, participants were challenged with responding to broad-stroke descriptions of the fictional quake’s effects; a lack of specifics mirrored what responders and managers could expect in a real crisis. As the exercise progressed, “injects”—bursts of new information—were introduced to complicate the emerging picture and challenge emergency managers’ priorities. Some injects were state-specific: a particular building in danger of collapsing, for instance. Others were more general, such as suspension or resumption of air or rail travel, or a report of severe damage to a dam that would have region-wide impact and require coordination across state lines.

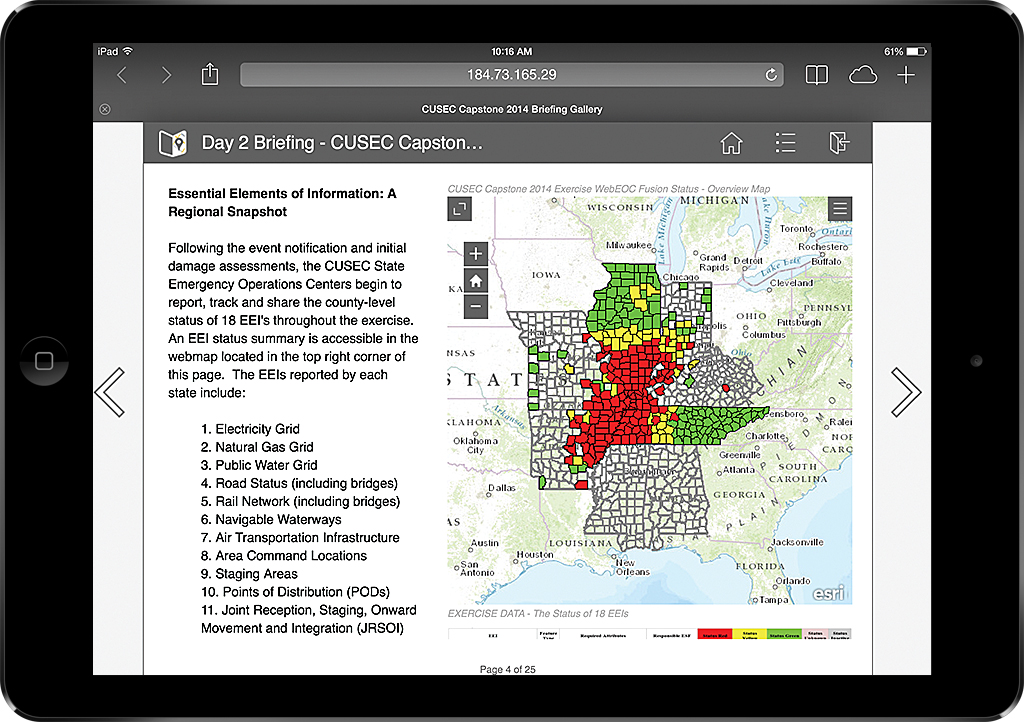

A multilayered map of all eight CUSEC states reflected continuously updated, county-by-county reports on all manner of data. Regardless of the means by which information was collected in a particular locale, essential elements of information (EEIs)—reports falling within predefined categories of critical data), such as evacuation orders or details on casualties or transport status—were standardized for exercise-wide viewing and consistent interpretation.

State operations centers had access to a COP viewer created in ArcGIS Online for organizations. To broaden access to this information, the viewer was also embedded into WebEOC, a crisis-management platform widely used by emergency operations teams.

“The COP contained layers such as road closures, open shelters, hospital status and emergency service routes and was enhanced by adding the same layers from adjoining states,” said Mike O’Connell, communications director for the Missouri Department of Public Safety. “Managers [in Missouri]had the ability to view all the nearest open shelters, for example, not just the ones that were available in Missouri. Emergency service routes extended beyond our borders for better routing.”

The ability to visualize information in a geographic format proved vital in the high-stakes scenario of a major quake, explained Jeremy Heidt, public information officer for the Tennessee Emergency Management Agency. “It’s much easier [for emergency managers] to comprehend a complex situation,” he said, “and assimilate [that data] with their knowledge of the communities in a state. Knowing where resources can easily reach also informs us of challenges that other communities might face from a lack of resources.”

Crowdsourced Situational Awareness

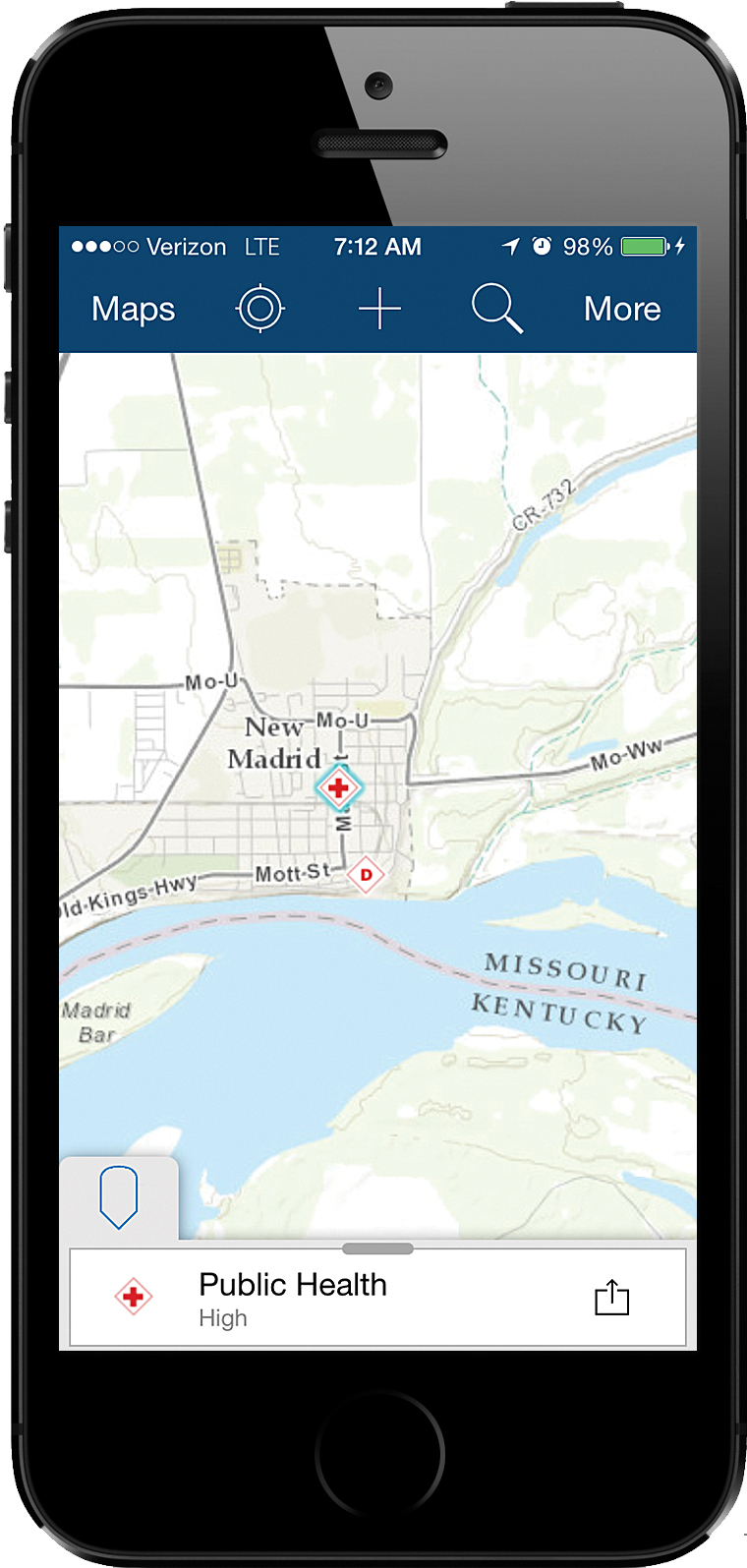

As the exercise unfolded, Esri developed a mobile app for responders and volunteers to assemble and share field reports quickly. The reporting process was as simple as checking a small set of boxes and required no more technical prowess than that required for sending a text message.

“The [mobile] application was used to crowdsource situational awareness data from the field,” O’Connell said. “Volunteers installed the app on their smartphones or tablets and then added points and photos for locations of fires, accidents, road closures, or floods.”

Incoming data from mobile app users was fed into Operations Dashboard so managers in each state’s emergency operations center could track events in real time. Such field reports, Monken added, couldn’t always be expected to provide an abundance of detail but often served to fill in “missing puzzle pieces,” to complete emerging pictures of situations on the ground and allow for informed assessments of impact.

“One of the problems we ran into was that a lot of gas stations didn’t have power, so they couldn’t pump fuel,” Monken explained. The lack of fuel access created obvious challenges with evacuation efforts, as well as the mobility of incoming search-and-rescue teams. “That was one of the things we wouldn’t have been able to see [without ArcGIS]. We could’ve only assumed that was happening without actually having good visibility. It was an opportunity to do a targeted prioritization of electricity restoration along an evacuation route we designated based on road information that we also wouldn’t have otherwise had.”

Other Esri technology came into play. Community Analyst was used to examine demographics in affected areas and refine evacuation strategies; identify potential cold-storage sites for temporary morgues; and locate possible respite sites along evacuation routes. Officials were provided quick updates on high-priority concerns via the Briefing Book. Briefing Book is a configurable ArcGIS app that can be used to create and view map-based briefings and reports that have interactive content. Esri Story Map apps proved a valuable public communications tool. Users could click points on the map to view photos and obtain information on shelters, evacuations, and damage at various locations.

The Future of Exercises and Response

CUSEC is already looking ahead to future exercises, with the goal of partnering with the private sector, as well as other disaster-mitigation consortiums in the West, Northeast, and “hurricane states” along the eastern and southeastern coasts to develop larger-scale drills. As the geographic scope of a Capstone-like exercise grows, so do the challenges of gathering and sharing information. Monken is convinced ArcGIS—specifically its utility in creating a comprehensive picture out of empirical data—will be the key to managing information in disaster scenarios, real or imagined.

“It’s just starting to be meaningfully incorporated into what we do,” he said. “Within a couple of years, we’ll realize GIS is the fundamental keystone of disaster response.”

Challenges may remain, though. Monken observed that emergency managers at all levels will need to become accustomed to managing data in greater volumes. For some Capstone participants, he explained, instant access to vast quantities of actionable information, reflective of real-time events, was initially overwhelming, simply because such access might not have previously been possible. Better situational awareness, he contends, brings with it a requirement that decision makers be prepared to view incoming data in context.

“People are quick to go to the tactical level when the information might really be intended for strategic-level decisions,” Monken explained. “You see information pop up and you want to play whack-a-mole—fix that problem right now—without understanding that you’re seeing a bigger picture in a way you’ve never seen before, and that it’s really serving as a system of strategic prioritization.”

Other Capstone participants and observers add that, in order for ArcGIS to be fully utilized in disaster management, state governments must ensure that managers and in-the-field responders at the county and city levels have access to the platform and the training to use it. Likewise, Monken added, it will become increasingly vital for ArcGIS users, both in government and in the private sector, to recognize the technology’s lifesaving utility in the context of public safety and be prepared to join conversations about deploying the platform in disaster response and management.

“We are light-years ahead, though, of where we were,” Monken said. “In an eight-state area, we had 440 counties reporting real-time, dynamic data into the system, which was unheard of. You can’t help but look down the road and think, the sky’s the limit with this.”