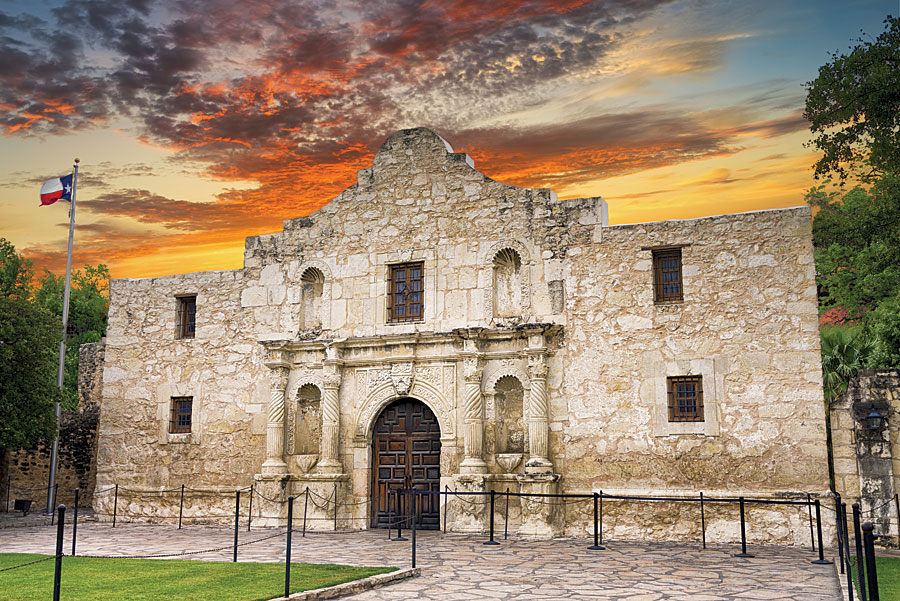

“Remember the Alamo” is the well-known battle cry that inspired the Texian Army to victory over the Mexican army at the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836 and ultimately led to Texas independence.

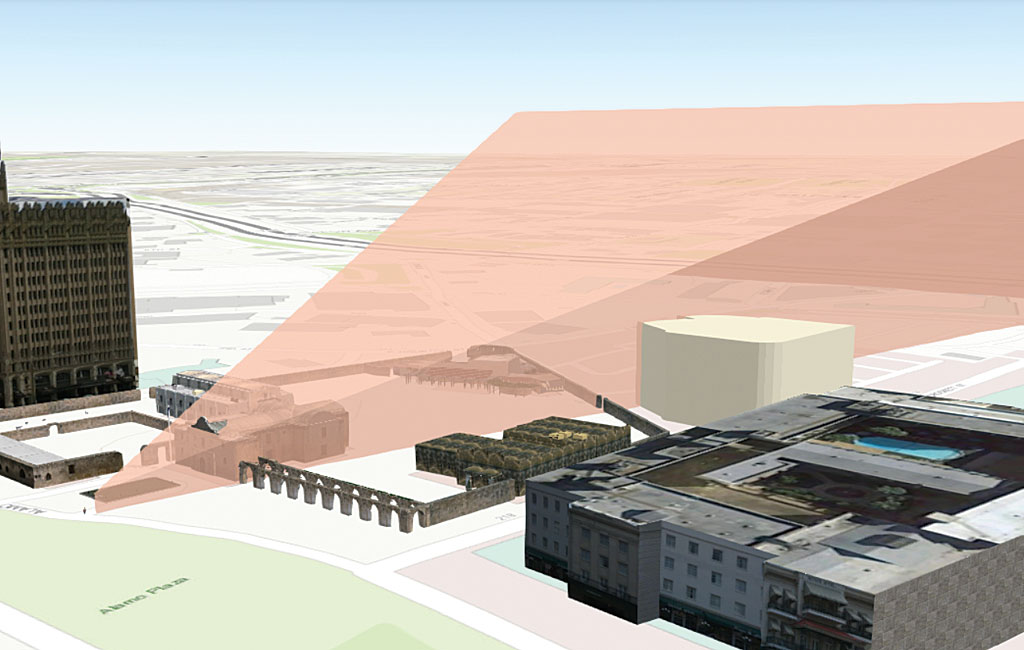

Engineers working on a project to restore the original site of the battle of the Alamo and preserve its viewshed are using 3D GIS visualization of the site as part of the restoration plan.

The original Alamo site—the Mission San Antonio de Valero—has been venerated for more than 180 years and visited by millions each year. Over the years, neglect and the mining of collapsed structures for building materials continued obliterating the site. Because of its location in the growing downtown section of San Antonio, Alamo and Houston streets were built across a portion of the original battleground. Later, the construction of a government facility, commercial buildings, hotels, tourist attractions, and conservation efforts further encroached upon this hallowed ground.

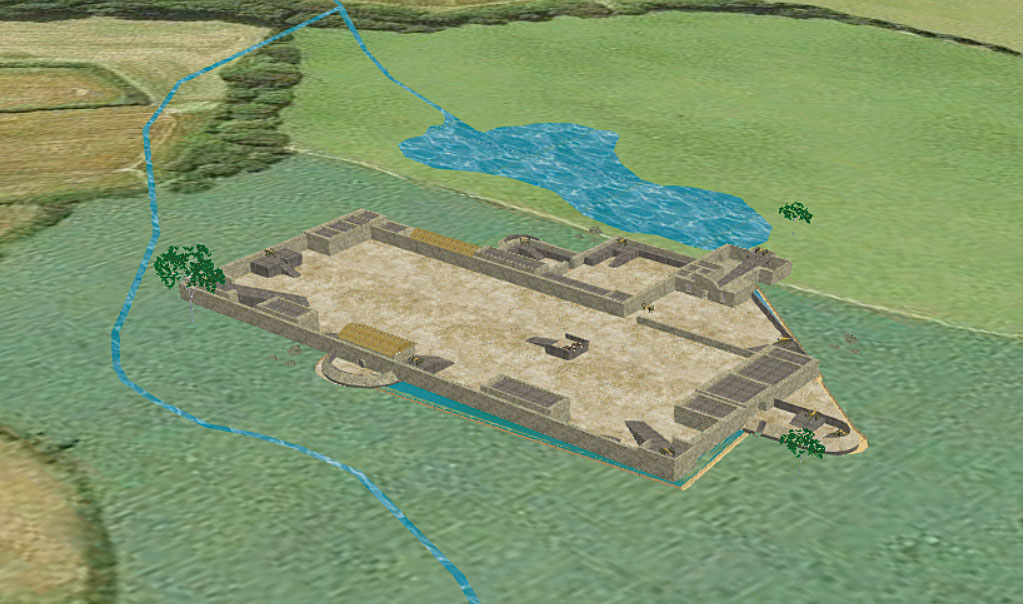

In honor of the 300th anniversary of the mission in 2024, the City of San Antonio and the Texas General Land Office have worked on the development of a major renovation plan for the site that accurately reflects the location of its 4.2-acre compound and historic buildings at the time of the battle of the Alamo.

The Mission San Antonio de Valero had been hastily converted into a makeshift fort. The garrison was composed of a large walled courtyard where the famed battle took place and a small number of outbuildings that included a chapel, storage rooms, animal pens, and the Long Barrack that provided living accommodations for the soldiers. Three-foot-thick walls surrounding the site were between 9 to 12 feet in height.

A Texas firm, Pape-Dawson Engineers, joined the group responsible for designing the reimagined Alamo site. The company led the archaeological effort to establish the exact location of the west and south walls of the compound. It also provided topographic surveying and laser scanning to document existing conditions and provide a historical basis for the concepts of redevelopment presented in the master plan for the Alamo Plaza site.

Michael Garza, GIS manager at Pape-Dawson Engineers, has been using ArcGIS for more than 15 years. As a San Antonio native, he took a personal interest in the plan to redevelop the Alamo Plaza as it appeared at the time of the 1836 battle.

“The Alamo is the most popular attraction in Texas,” said Garza. “The site gives our city an enormous sense of pride.”

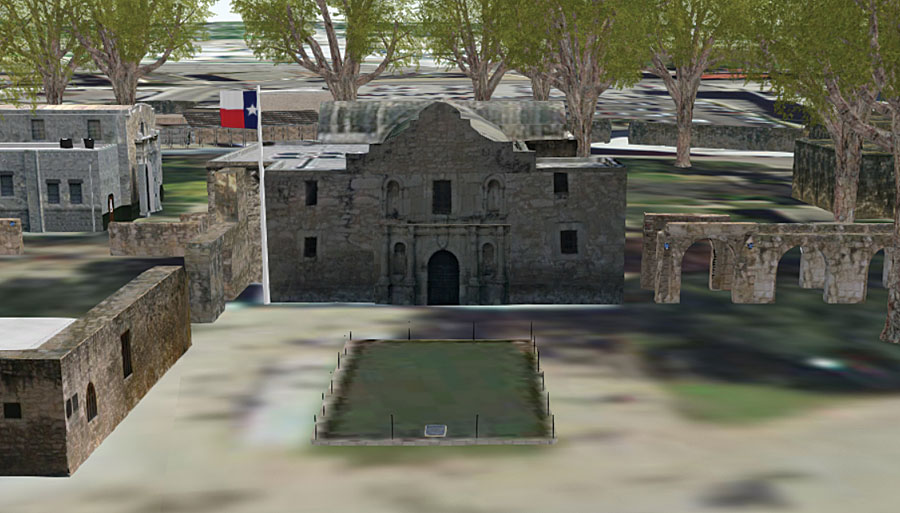

Garza was interested in the work done by Pape-Dawson’s archaeological crew members at the site, especially when they determined the location of the Alamo’s long obscured walls. He convinced the company to let him contribute to the project by visualizing the site as a precise 3D model using GIS. This model would not only aid those involved in the reconstruction project but could also provide an accurate historical perspective for those visiting or researching the Alamo.

“First, a basemap was created for the 3D models by clipping an image of the Alamo Plaza site from Pape-Dawson’s existing aerial data, and then [Trimble’s] SketchUp was used to create the bare earth courtyard where the battle took place,” said Garza.

“A 3D historical model of the Alamo compound already existed in Trimble’s 3D Warehouse, which is an open-source library of SketchUp images. We compared this model with several artist renditions of the Alamo for the 1836 time period and determined that it was historically accurate,” said Garza. “We then resized and repositioned this model to match the exact location of established artifacts on the basemap, such as the west wall bricks found by our lead archaeologist Nesta Anderson.”

Garza’s team got the information needed to create 3D models of the missing buildings and walls from artists’ renderings of the Alamo from that period, as well as from a sketch used as part of the Mexican battle plan that was made by one of General Antonio López de Santa Anna’s senior officers. Footprints of the existing buildings around the perimeter of Alamo Plaza came from a GIS layer the team received from the City of San Antonio that included building footprints and heights.

Garza described the process used to produce the 3D models of the buildings and walls. First, the missing 2D footprints were created in ArcGIS Pro, extruded in 3D, converted to multipatch features, and saved in the project’s geodatabase. Extrusion heights were based on the recorded building height found in the GIS database or, in the case of those buildings that had been destroyed, on historical research.

The multipatch feature was exported as a COLLADA file, a 3D interchange format that is compatible with SketchUp. In SketchUp, textures were added to building facades to make them appear realistic. Textures for the facades were created from photos of building exteriors and walls taken by the team. The team made sure the images overlapped so they could be accurately applied to the 3D models in SketchUp.

Each SketchUp-enhanced model was brought back into ArcGIS Pro as a Keyhole Markup Language (KML) file, converted back to a multipatch file, and reprojected for positioning purposes. All 3D buildings were added to the basemap using the Layer 3D To Feature Class tool in ArcGIS Pro to create a photo-accurate, geolocated 3D model of the Alamo Plaza site.

“The final interactive piece provides past, present, and future views of the Alamo Plaza. It was published as a web scene in ArcGIS Online to make it easily accessible from any web browser and compiled into a story map so that a written narrative could enhance it,” said Garza.

See the Esri Story Maps app, “The Alamo: The mission, The Battle, The Legend,” created by Pap-Dawson Engineers.