In her opening remarks to the sixth annual (and second virtual) Esri Science Symposium, Esri chief scientist Dawn Wright emphasized Esri’s strong connections with the scientific community. Held on July 15 in connection with the 2021 Esri User Conference, this exclusively virtual event with 3,039 attendees was more inclusive than the most recent in-person Science Symposium in 2019, which was attended by approximately 700 people.

In addition to the scientific foundation of its software and tools, Esri is active in the international scientific community on various boards, councils, and research projects. It works collaboratively with some of the world’s largest earth science organizations, focusing on six areas: open science, weather and climate science, ocean science, solid earth science, geographic information science, and social science. Soon Esri will add qualitative social science as a seventh area of emphasis.

Biodiversity Feeds, Shapes, and Saves the World

In keeping with the Esri User Conference theme, GIS—Creating a Sustainable Future, Healy Hamilton, PhD, and chief scientist for NatureServe, delivered her symposium keynote speech, “Biodiversity and Global Change: The Spatial Nature of Conservation.”

Hamilton is a biodiversity scientist by training with graduate degrees from Yale and the University of California, Berkeley. She leads a staff at NatureServe who have expertise in ecology, zoology, botany, conservation, data science, and information management. Together they produce foundational information on the distribution and conservation status of species and species habitat. NatureServe, Inc., is a nonprofit that provides biodiversity network information, data, and tools that support conservation practices based on science.

Hamilton noted that the well-being of individuals and communities is utterly dependent on the natural world, so conserving the diversity of life is essential to our survival. Hamilton began by describing the vital role biodiversity plays in feeding the world. “Every single calorie ever consumed by all of mankind in all of human history comes from biodiversity. Supplying enough safe and nutritious food for a rapidly growing world really requires we increase food production globally without undermining planet capacity, to meet the needs of future generations and deliver other essential ecosystem services,” she said.

The mission of balancing biodiversity preservation with feeding a population of billions is hampered by the current food production system, which relies on just 15 crop plants for 90 percent of food energy intake and ignores some 200,000 plant species with edible parts. As climate patterns change, the yield of this limited number of crops declines and food sources become less secure.

She pointed to the Dongria Kondh, a tribe that lives in southwest Odisha, India, as an example of people who appreciate and protect biodiversity. The government had introduced high-yielding rice varieties and encouraged the tribe to abandon the assortment of resilient heirloom rice varieties they were growing. When it became clear that the monoculture advocated by the government jeopardized the agricultural self-sufficiency of the Dongria Kondh, the tribe recognized that diversity equals security and returned to its previous practices and prosperity.

Biodiversity also ensures that the food supply by supporting pollinators—from bees to bats—provide ecosystem services valued at between $200 to $400 billion each year. Human well-being also depends on biodiversity in other ways. More than half the drugs approved in the last 30 years have been directly or indirectly derived from natural products. The study of nature has also been beneficial in devising more effective treatments for chronic conditions. For example, the nerve regeneration of sea cucumbers is being studied and could lead to a cure for Parkinson’s disease.

Hamilton highlighted the potential of biomimicry, a relatively new science that uses inspiration from the many ways that nature has evolved systems and strategies that can be applied to solve existing engineering problems. She used the nearly unsquishable diabolical ironclad beetle (Phloeodes diabolicus) as an example. It can withstand pressure that is 39,000 times its body weight, so it is being studied by materials scientists for developing armor, building, and packaging applications.

The value of biodiversity goes beyond direct benefits to our food, medicine, or materials. Many species are ecosystem engineers that directly or indirectly change their environment, making resources available to other species. She used sea grass beds as an example. They buffer coastlines from storm surges, provide habitat for commercially important marine species, and remove carbon from the atmosphere more rapidly than tropical rain forests. Although sea grass beds cover less than one-fifth of 1 percent of the seafloor, they are responsible for about 10 percent of the carbon uptake from the oceans. In summary, Hamilton affirmed, “We rely on biodiversity every day.”

Despite the undeniable value of biodiversity, the number of species is declining precipitously, as demonstrated by the fate of beetles, a group with the greatest species diversity. Sixty percent of beetle species with an International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) conservation status have been identified as threatened.

Manage, Protect, and Restore

“How we manage the natural world will determine the future quality of life on Earth,” Hamilton declared. Managing the natural world is an intrinsically spatial problem that requires identifying the location of areas of intact ecosystems that need protection and degraded areas that need restoration.

Essential to these management processes, GIS can assess the spatial distribution and intensity of human influence, monitor existing protected areas, and guide the establishment of new protected areas. Protected areas are fundamental in efforts to protect biodiversity. The great strides made by the conservation community in adopting standardized approaches to identifying and delineating key biodiversity areas complements the mapping of these areas.

Hamilton traced the development of the conservation movement from its genesis in 1968 and early work by The Nature Conservancy (TNC), which began creating the first biodiversity information network in 1974. TNC established nature heritage programs in every US state and expanded throughout the western hemisphere.

This network of heritage programs was spun off from TNC to become NatureServe in 2000. This network systematically inventories species and ecosystems and their locations and status. NatureServe has amassed over a million mapped locations of species populations over the past 50 years. However, while this data is valuable, it is incomplete. This means that NatureServe had to find a more comprehensive method for answering one of the most fundamental of all conservation questions: Where do imperiled species live?

Spatial Advances in Species Protection

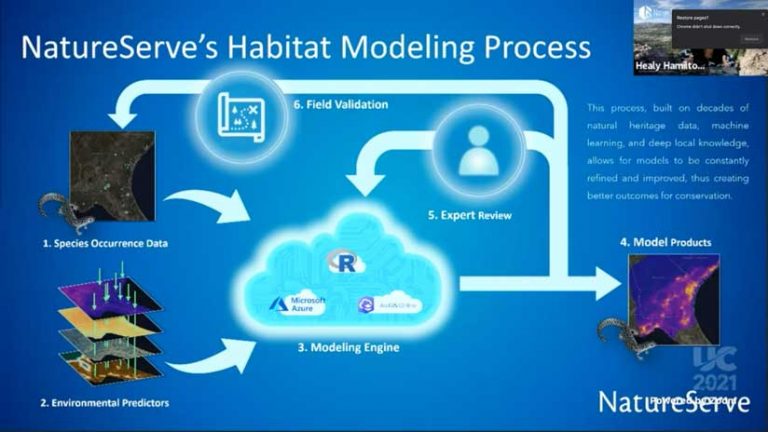

NatureServe has fully embraced the integration of its 50 years of high-quality species data with spatial data on the environment, modern ecological modeling approaches, and cloud computing. NatureServe partnered with Esri, TNC, Microsoft, and experts across its network to produce a suite of national analyses called the Map of Biodiversity Importance (MoBI).

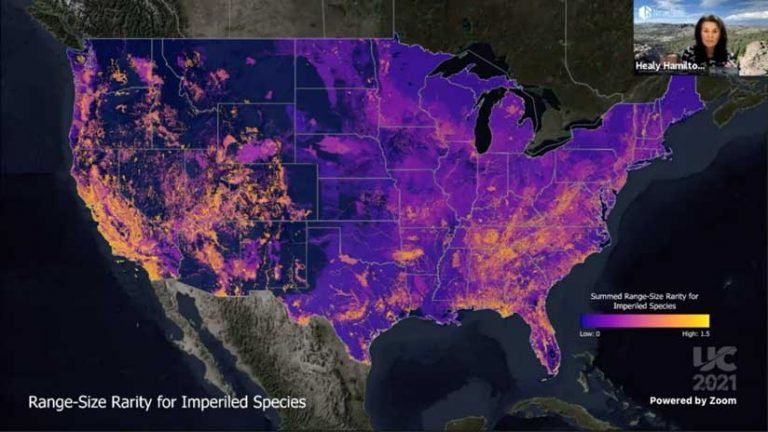

A series of 15 maps, with three different spatial analyses and five different taxonomic groups, MoBI can help set conservation priorities for 2,216 imperiled species. Data was aggregated and analyzed to reveal spatial patterns at unparalleled detail. These maps are freely available from the ArcGIS Living Atlas of the World. They are being used by many organizations, such as electric power companies, to guide land management.

Not just a set of static maps, MoBI is a dynamic habitat modeling system that lives in the Microsoft Azure cloud. It incorporates decades of natural heritage data, machine learning, and local knowledge to constantly refine and improve MoBI. A geospatial tool allows species experts and managers to improve model results in a transparent and collaborative process. Hamilton described the change in the capabilities provided by MoBI as transformational in its level of precision.

In closing, Hamilton emphasized that human actions have made everyone ecosystem managers, “so we need to be better ones. We need to protect what is left and restore what is degraded. That is a spatially explicit set of directions. The Science of Where and the science of conservation are absolutely intertwined.” She urged the audience to join one of the many nature networks to work to protect and preserve the world’s biodiversity.