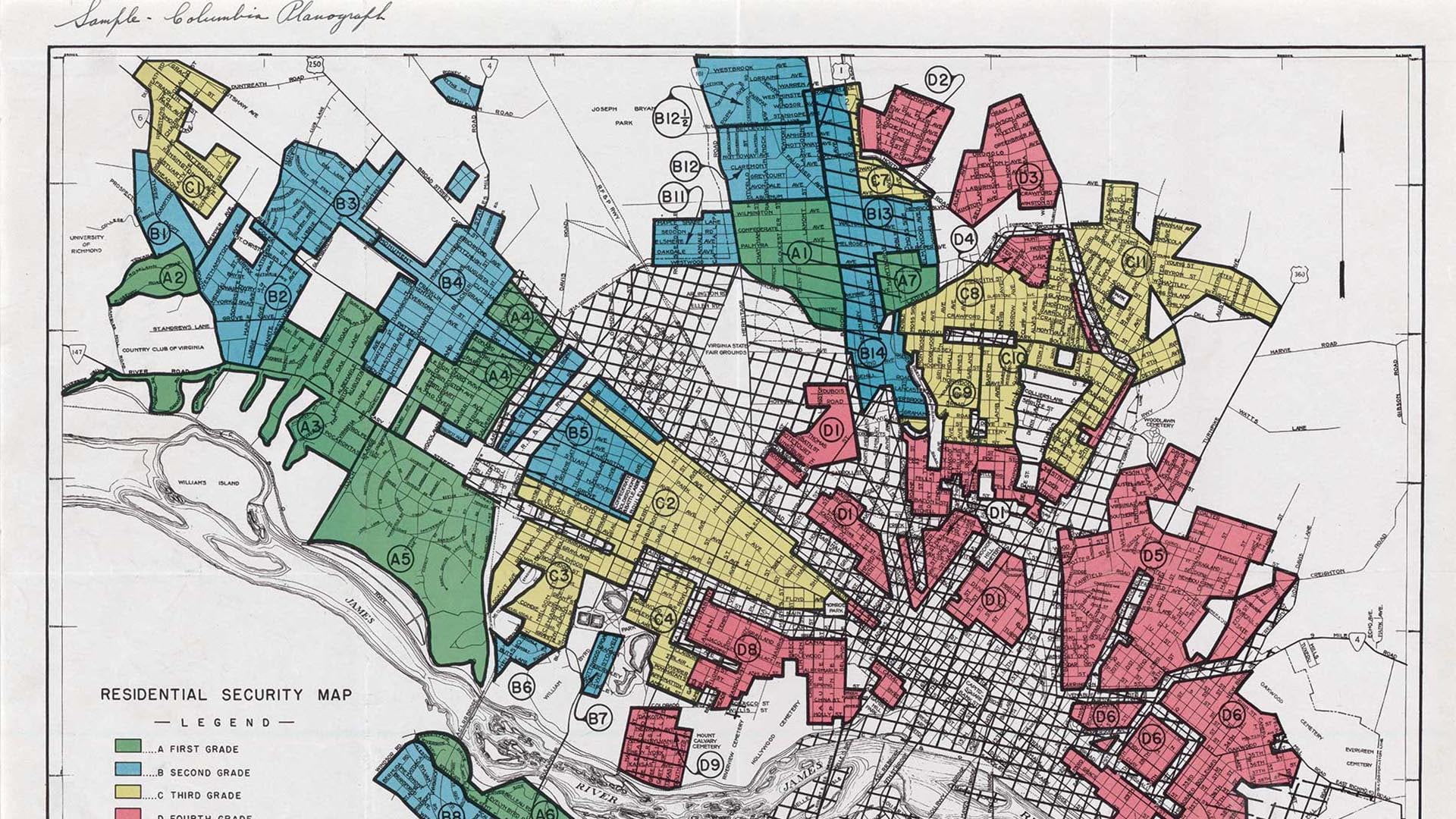

Roxana Ayala was introduced to GIS technology while working on a high school research project in 2013. GIS helped Ayala and her fellow students see their lived experience in a new light. This powerful technology helped her better understand the historically underserved neighborhood of Watts in the City of Los Angeles where she grew up, and Boyle Heights, another area of the city, where she went to school. Her connection to GIS has been guiding Ayala’s career ever since.

Two Mentors and a Changed Life

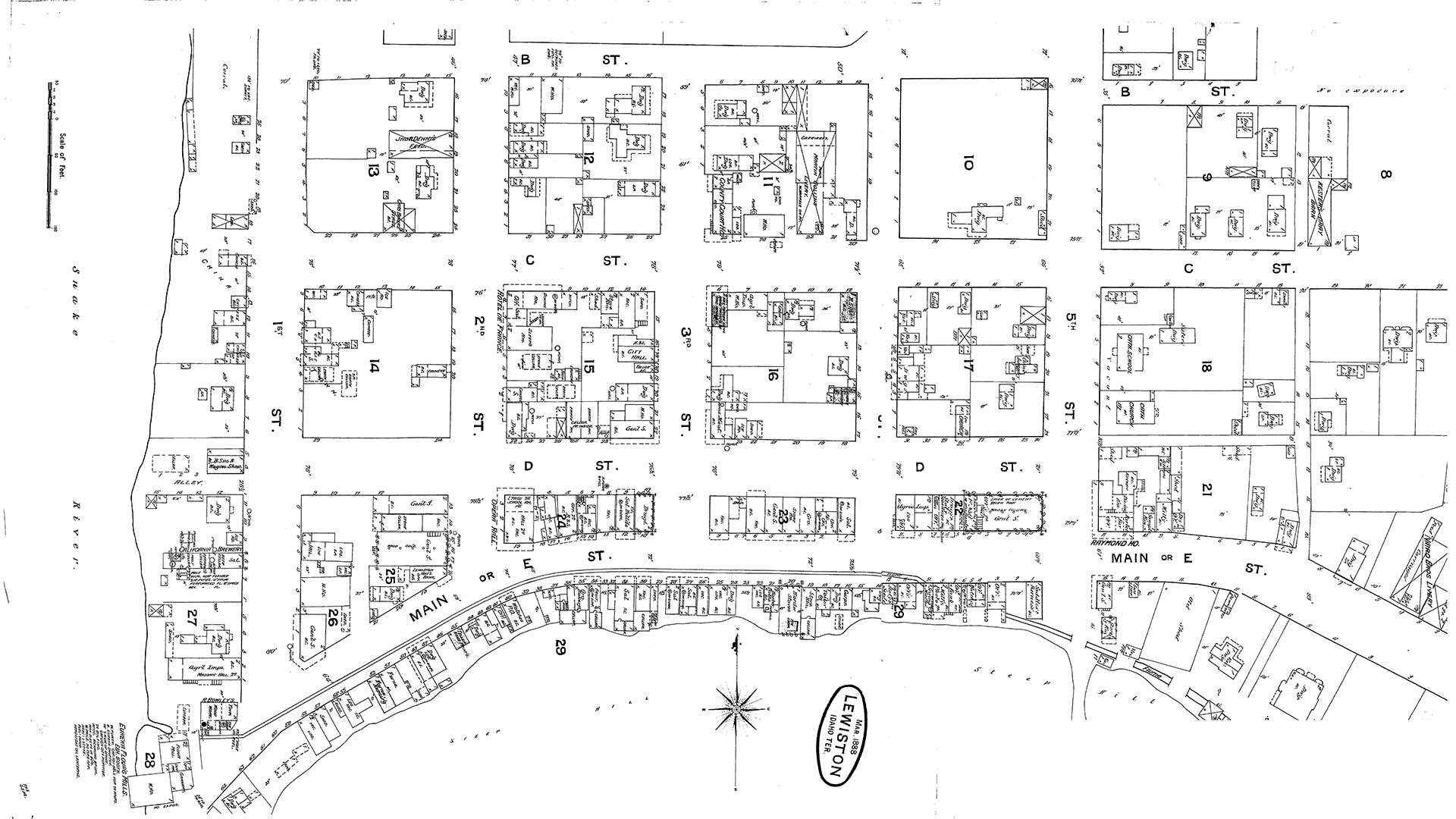

Working in teams to investigate a social justice topic, students at the Math, Science, and Technology Magnet Academy at Roosevelt High School engage GIS in their service learning projects to build a deeper understanding of their community.

Empowered by GIS-based research on their local neighborhoods and city, students began to ask that all-important question: Why? Teachers note that their students develop a maturity and a confidence through GIS projects that change the way they think.

Alice Im and Mariana Ramírez, who both taught Ayala at Roosevelt High School, recall her as a bright student and a spirited, somewhat fearless kid. In Ayala, her teachers saw a smart teen who was always serious and engaged.

With their guidance, Ayala learned the power of plotting data-based analysis on a map in strikingly visual ways. Ayala’s high school project focused on evaluating education inequalities. She saw the discrepancies in education, income, housing, health care, and environmental safety between her community and more financially secure neighborhoods.

“I love Roxy,” said Im, an English teacher. “And I think Mariana will back me up on this…we have many, many students like this, where they are just so resilient and so capable of becoming these powerful, wonderful human beings.”

“GIS helps them to really understand their community, so that their relationship with their community isn’t a negative one, where they believe this is a terrible place that I need to escape,” Im said. “Rather, it’s like this is a really wonderful, beautiful place that has a lot of challenges, and that I can be a leader and I can transform it and take ownership.”

Asking Why

Location intelligence made the student researchers even more alert to current events.

“Our students began to question the budget cuts that were happening systematically across the State of California,” Ramírez said. “And they were noticing how California, having one of the richest economies in the world, was undercutting the educational system, and they were asking why.”

Though currently pausing her teaching career to pursue a doctorate degree in education at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Ramírez is anxious to get back to teaching. She and Im believe that location intelligence from GIS can have a similar effect on students and teachers at other schools, especially in historically marginalized areas.

“There’s not enough examples of communities like ours that are in working-class, people-of-color neighborhoods that are engaging in this type of work,” Ramírez said. “So I think one of our goals as teachers and educators and researchers is to one day put out some work on this for the educator community.”

Their students’ work, however, already has drawn attention. In 2013, Ayala and three other high school classmates presented their findings at the Esri User Conference in San Diego, California. Their work inspired GIS users from around the world. Since then, the students from Roosevelt High School have made an annual trip to the Esri campus in Redlands, California, to share how GIS enhances their understanding.

As Ayala entered the University of California, Irvine, her skill with GIS, a technology few of her peers even knew about, opened new opportunities for her. She frequently used GIS in courses she took on her way to earning a bachelor’s degree in environmental science and urban studies. She also completed a summer internship at the University of Minnesota, using GIS to analyze manufactured homes across the United States and their vulnerability to environmental factors such as flooding and air pollution.

Her passion to make a difference has continued to drive her work. Ayala now conducts research and provides technical assistance at the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE), a Washington, DC-based nonprofit, 501(c)(3) organization that aids in advancing energy efficiency policies, programs, technologies, investments, and behaviors. She began at ACEEE with the assistance of the Roger Arliner Young (RAY) Diversity Fellowship Program. [The RAY Diversity Fellowship Program supports conservation, energy efficiency, and renewable energy-related career pathways for emerging leaders of color.]

She is most concerned with energy equity. “Clean energy-related efforts that are developed in an equitable, just, and fair manner can offer many benefits, especially to marginalized and Black, Indigenous, and people-of-color communities,” Ayala said. “As we work to develop recommendations for policy makers, utilities, and other key stakeholders in the clean energy industry, we must ensure that these efforts reduce energy costs; promote the health, safety, and well-being of people; and work towards reducing carbon emissions that contribute to climate change.”

Last year, Ayala and her colleagues published Expanding Opportunity through Energy Efficiency Jobs: Strategies to Ensure a More Resilient, Diverse Workforce, a report that examines energy efficiency workforce development programs that emphasize diversity and inclusion.

The Value of a Geospatial Approach

“I still approach problems using the geospatial critical-thinking techniques I learned in high school,” said Ayala. “It has become the foundation for my research method—looking for relationships and connections.” In her policy work, Ayala said she makes a point of focusing on equity-centered strategies that will promote diversity, justice, and inclusion so that everyone has access to the benefits of programs and policies.

That underscores something her former teachers, Im and Ramírez, have noticed when their students talk about possible careers. “A lot of our very talented young people are saying, ‘I would like to go into public policy, and I would like to go into work like that where I get to make certain types of decisions about how things are managed and how resources are distributed,’” Im said.

Ramírez added that when students get excited about turning research into policy and policy into action, they inspire their mentors. “We’re constantly also growing and learning from them about their imaginings of how we can create a better future for youth and people of color.”

GIS Maps the Way Back Home

GIS provided a career path that led Ayala to opportunities outside her neighborhood, but it has also provided a road back to that community.

“I struggled with outside factors and many systemic barriers to get to the place I’m at now,” Ayala said. “People in my community lacked adequate resources but helped me in other ways. My success has been a community effort, with many mentors, friends, family members, and individuals that helped me along the way. I also worked very hard.”

The school and community support she received helps Ayala see herself as someone who can give back to her old neighborhood. On a recent visit, she toured the area with her former teachers. Ayala pointed out polluted spots and food deserts but also beautiful murals that make her proud—and, in turn—make her former teachers proud.

Ramírez said that they all seemed to share a similar point of view shaped by GIS. “How can we create a better living and learning opportunity for all the youth that live here in my neighborhood? And how do we enrich this place for them and for their future?” she said.

Learn more about using GIS to teach K–12 students and the free teaching resources available from Esri.