In Brisbane, the most rapidly growing city in Australia, a digital twin and a virtual reality program guide the design and construction of an underground railway.

The team tasked with designing the first underground railway under the heart of Australia’s fastest-growing city knew it would be a delicate task, fraught with infrastructural peril. The project’s scheduled completion was less than two years away. It required tunneling several stories under Brisbane’s teeming metropolis and constructing expansive subterranean stations. What could go wrong?

At the outset, no one knew that the effort would involve an ingenious application of GIS, the creation of a detailed and up-to-date 3D model of the underground project and the city above it, and an immersive digital twin to bring the project to life.

A Rapidly Growing Queensland

The Queensland government conceived the Cross River Rail project as a way to alleviate population pressure. By 2036, the South East Queensland metro area is projected to add another 1.5 million residents (a number that by itself would make it Australia’s fifth-largest city), pushing the region’s total population to nearly 5 million.

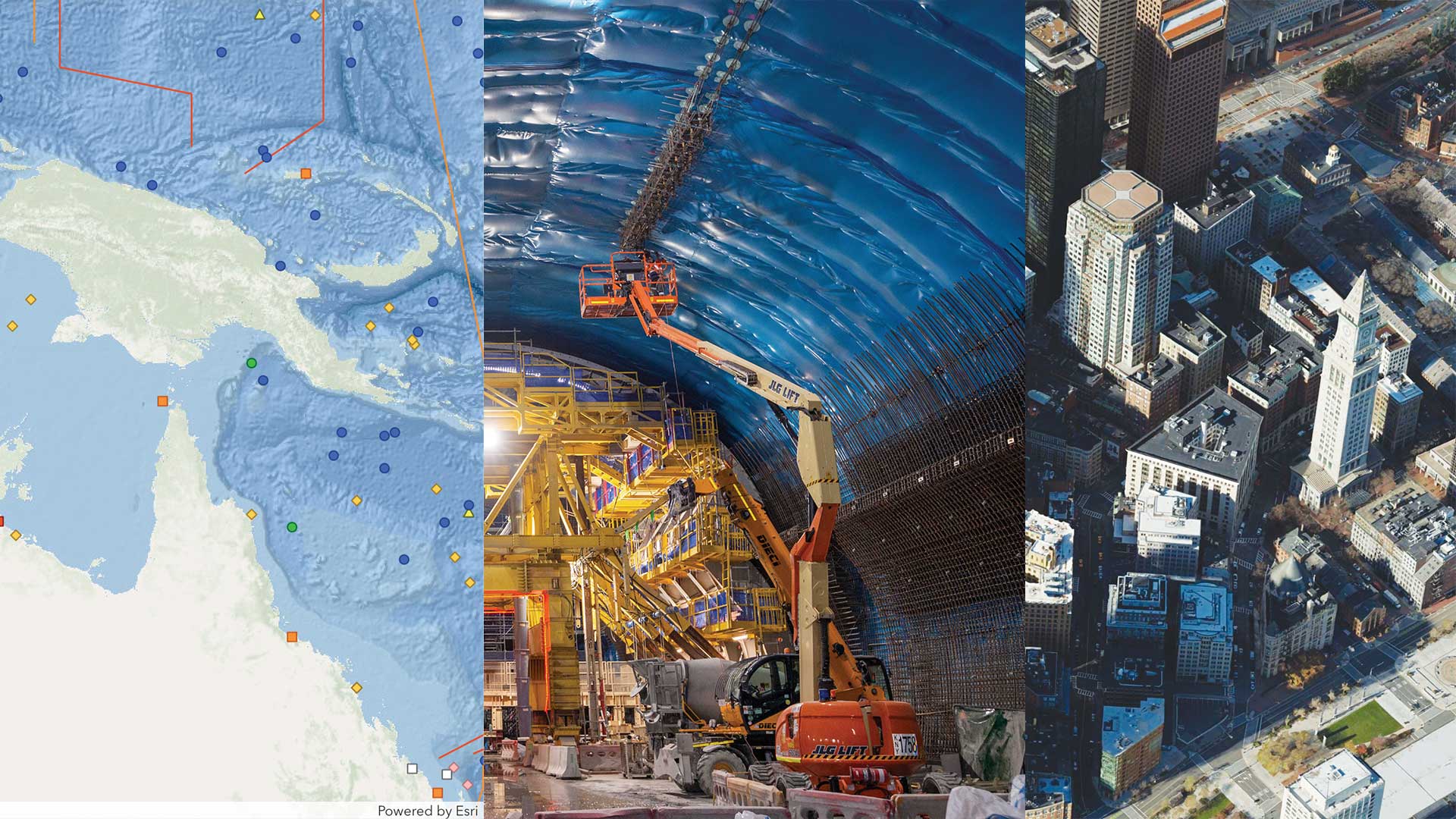

The Cross River Rail project will deliver a new 10.2 kilometer (km) line through Brisbane’s inner city, featuring twin 5.9 km tunnels running under the Brisbane River and the central business district (CBD). Four new underground stations will be built as part of the AU$5.4 billion project, in addition to the upgrade of eight existing stations.

Most of the new metro residents will live outside of Brisbane but within commuting distance. Many of the new jobs, however, will be in the Brisbane CBD, on the north bank of the Brisbane River.

Current rail infrastructure is insufficient to handle the increase in CBD-bound train traffic that will be necessary to handle these commuters. Cross River Rail will add twin tunnels under the river and four additional underground stations to handle this demand.

A Bigger, Better Model

The Cross River Rail Delivery Authority, the Queensland government agency overseeing the project, sought advice from colleagues on the other side of the world soon after the project was announced. Crossrail, a construction project in London that launched in 2009, has similar aims. The project is creating new tunnels and 10 new underground stations throughout Central London.

Crossrail involves construction beneath a metro area even denser than Brisbane’s, with extremely narrow margins to avoid damaging existing underground infrastructure.

By the time Cross River’s plans were beginning, Crossrail had been under construction for almost seven years. The Cross River team contacted its British counterparts and asked what, if anything, they would do differently if they could start over.

“They basically said, ‘We would have built a bigger, better 3D digital model sooner,’” Vine said. Crossrail then offered three steps for building the perfect GIS-driven digital twin:

- Create a common data environment.

- Stipulate that all contractors use the same standards in their 3D architectural models so that they can all be combined into a single model for the project.

- Make the model immersive.

An Expansive Mission

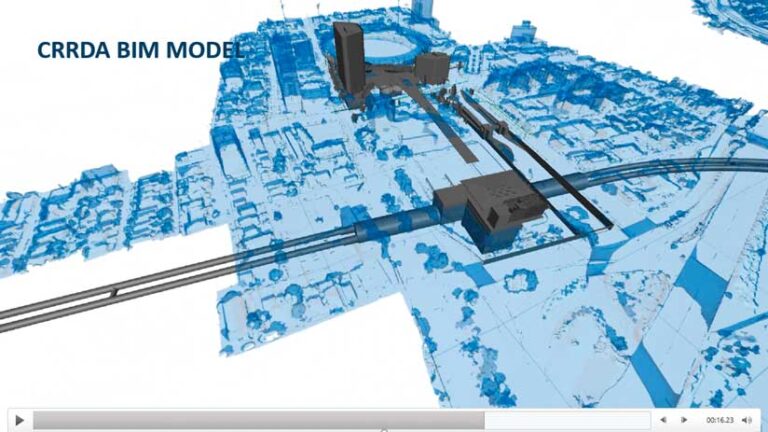

For starters, Crossrail recommended that Cross River create a common data environment for all work. Any project-related dataset, no matter what the format should be in a central repository. That included GIS, building information modeling (BIM), volumetric data, and photogrammetry (a three-dimensional coordinate measuring technique that uses photographs).

In recent years, GIS technology has become adept at integrating BIM models and other project-related data formats into a GIS environment. BIM models are 3D architectural models that describe and depict the things being built or dug, while GIS adds contextual awareness for those things. Rather than considering BIM models as just inert objects floating in space, the people involved in a project can visualize what’s around them. In GIS they can see how each structure fits into the infrastructure aboveground (such as paths, roads, and light poles), underground (the pipes and lines that connect utility services) and the natural world (landscaping, groundwater, and even wildlife and biodiversity considerations).

The advice also helped Cross River handle a broad mandate. When Queensland’s government created the Cross River Rail Delivery Authority, it required the agency to be responsible not just for the railway itself, but also for planning and assessing the project’s economic impact.

There was a good reason to include this mandate in the agency’s charter. Although Cross River anticipates future developments in the region, its location means Cross River will also influence those developments.

“Cross River Rail is going right under the CBD, so the area around the stations is already prime land where the city will grow next,” Vine said.

Everything in Federation

Crossrail’s second piece of advice to Cross River related to BIM data coming from the project’s many contractors and subcontractors. Crossrail staff urged Cross River to create a “federated” BIM model. That meant combining the disparate BIM information into a single BIM file that depicts everything. For that to happen, Cross River needed to ensure that every contracting entity was using exactly the same data formats, standards, and protocols.

“What the Crossrail team didn’t realize until it was too late is that all their contractors were telling Crossrail how they were going to submit their BIM models—it was baked into the contracts,” Vine said. Crossrail indulged their contractors and realized later that they should not have done that.

Rail Games

Crossrail’s third recommendation is “the party piece, the one everybody loves,” Vine said, because it’s about making the model immersive. “They told us they should’ve put all their data into a game engine and turned it into virtual reality.”

Putting BIM models into Unreal Engine, a 3D gaming tool, allows engineers and other stakeholders to experience each station before they build it. The Australian team used Unreal Engine so that anyone could be virtually transported inside the place they were set to build.

“So, we have a federated BIM model of all the stations and all the tunnels, and GIS land mapping in 3D,” Vine said. “But then we put it all into Unreal, crank the magic gaming engine handle, and it gives us back a single virtual reality.”

The result is 17 kilometers of immersive railway infrastructure that can be explored—like a first-person game—on a screen manipulating a web scene or with a virtual reality (VR) headset. The Cross River team even built a virtual reality theater using a five-way projection system, so many people can explore the project together.

The virtual reality component transcends mere flash, providing a way for nontechnical stakeholders—people not directly involved in the design and construction of Cross River—to view the project as it proceeds. It also gives those who are part of the design team the kind of visual assessments that even the most detailed 3D BIM model cannot provide. As one example, Vine points to the Roma Street station, where teams are experimenting with ways to install a massive art exhibition space on a concourse wall, trying and testing different ideas virtually before they finalize the design and build it.

The Digital Twin Expands to Capture All of Brisbane

Cross River’s commitment to the common data environment signaled a shift from the usual relationship between GIS and BIM on this kind of large infrastructure project. In the past, GIS would have provided crucial support by providing context for 3D architectural BIM renderings. Given the mandate to document economic development around the train stations, Cross River elevated the importance of GIS. To depict those aboveground areas, Cross River would require skillful 3D maps, including data gathered by lidar sensors to capture engineering-grade measurements.

That, in turn, led to another requirement. The aboveground data would also require context.

If the goal was to understand how the stations would affect economic development in the CBD, it didn’t make sense to map just the area around them. A map of the entire CBD was required. Everything would need to be layered perfectly so that everything underground lined up exactly with everything aboveground.

The result is a 3D land layer that shows lots, utilities, and other pertinent visual information. Cross River’s use of 3D even includes material designed in consultation with Brett Leavy, a self-described “cultural heritage digital Jedi,” who uses advanced VR technology to re-create precolonial Brisbane. Leavy’s input, Vine explained, has helped ensure that the project honors and remains respectful of indigenous peoples.

“We went from, it’s all about building a railway, to ah, it’s also about rebuilding the city,” he said. “We ended up making a 3D model of Brisbane, because it was impossible to do one without doing the other.”

A Twin Without End

The Cross River digital twin is a continuous work in progress. As designs are finalized and construction proceeds, a staircase or tunnel that existed as a single item in a contractor’s initial BIM submission becomes one with thousands of individual components in the federated BIM model.

Beyond just the Cross River project, there’s no reason the digital twin can’t continue to grow in perpetuity, evolving with Brisbane itself. “We have a running joke about Cross River Rail, that the more you look at it, the bigger it gets,” Vine said, noting that after the project began, the city was selected to host the 2032 Summer Olympic Games.

“We have an opportunity to take what we’ve done here as part of building a railway line and stretch it to include everything we’re going to need to build for the Olympics,” said Vine.

Vine foresees the twin being a tool for operating the system in addition to its value in design, construction, and project management. “We realized we’ve built a digital twin that will help run the railway,” he said. “So, there’s almost a whole second chapter waiting to be written.”