The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, more commonly known as Kew Gardens, uses GIS to fulfill its stated mission “to unlock the potential of plants and fungi, through the power of scientific discovery and research.” The facility supports conservation, research, and education programs.

Although its origins can be traced to the merging of the royal estates of Richmond and Kew in 1772, Kew Gardens was formally founded in 1840. Located in southwest London, Kew Gardens maintains the largest and most diverse botanical and mycological collections in the world. Its living collections include more than 27,000 taxa. It houses more than 8.5 million preserved plant and fungal specimens. Kew Gardens also is a repository for research materials, with a library containing more than 750,000 volumes and a collection of more than 175,000 prints and drawings of plants.

Since 1750, 571 species of vascular plants have become extinct. Vascular plants are characterized by specialized tissues for the internal transport of water and nutrients. The number of extinct species was determined through an extensive examination of peer-reviewed scientific publications by Rafaël Govaerts, a botanist at Kew Gardens. For the past 30 years, Govaerts has rigorously reviewed all known books on plant extinctions. “The real figure is undoubtedly higher, and a continued effort is under way to assess the threat status of each plant species,” said Govaerts.

Sustainable Management and Protection

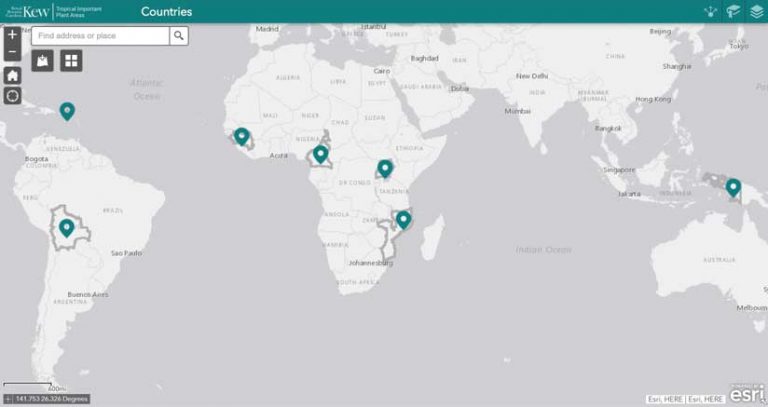

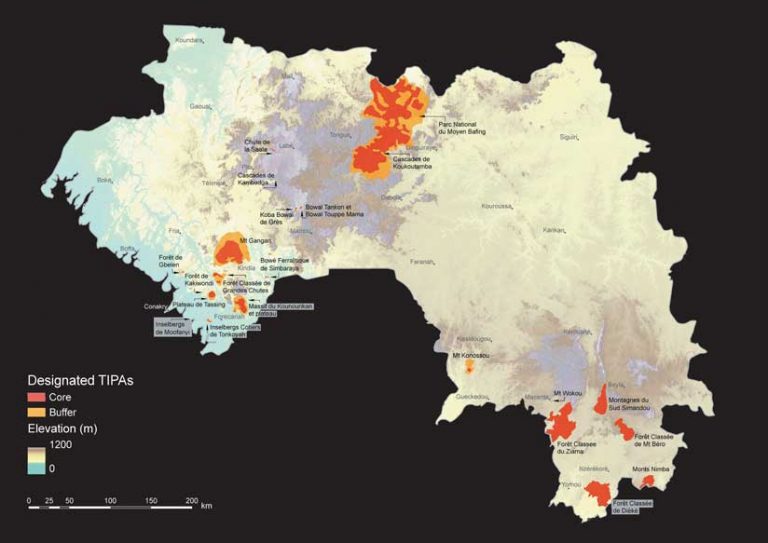

Among its conservation programs, Kew Gardens initiated the Tropical Important Plant Areas (TIPA). project. The first phase of this project includes delimitation and mapping of concentrations of threatened plants in Bolivia, the British Virgin Islands, Cameroon, Guinea, Indonesian New Guinea, Mozambique, and Uganda.

The TIPAs project uses a revised Important Plant Areas (IPA) methodology that was developed in 1989 by Plantlife, the British wildlife charity. This methodology is used to assess plant conservation priorities at both the regional and national levels. Priorities are based on research, surveys, and expert knowledge. The TIPA designation is reserved for an area sustaining a threatened species or habitats, or one of botanical richness that includes useful plant species. The goal is to promote sustainable management and protection of TIPAs through engagement with policy makers, landowners, and international initiatives.

“We have used ArcGIS Online for the TIPA project since we began it in 2015,” said Jenny Williams, a senior spatial analyst at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. “It is used by botanical experts to inform decisions critical to TIPA designation, and especially in relation to imminent threats to the flora from agricultural expansion, mining, illegal logging, wildfires, and dams.” A portal for TIPAs that will link to ArcGIS Online maps is currently under development.

“Our work is in developing countries that have limited access to current IT technology. Often, their computers are old, and the internet speeds are slow. In addition, they have little knowledge of GIS concepts, so I set up a framework that they can use to document their findings,” said Williams.

She provides these countries with a digital map of satellite imagery so local experts can digitize the location of endangered plant species and other key habitat areas on the map. A botanist will then analyze those maps to determine if endemic species are present in the indicated areas and if they are at risk and should be protected. Conversely, botanists also determine if an area has been cultivated for agriculture or degraded in other ways. There is little point in trying to protect these areas.

Regional groups meet with key staff in workshops to determine which areas to protect and the best way to do that. The findings from these workshops are presented to the government to implement procedures to protect critical habitats. The maps have also been used to guide collaborative fieldwork efforts, which sometimes result in the discovery of new species.

Williams is trying to get the TIPA proposed protected areas added to the ArcGIS Living Atlas of the World. ArcGIS Online lets Kew staff members easily distribute their findings and analyses through internet browsers. They also use ArcGIS Pro, ArcGIS Image Analyst, ArcGIS Spatial Analyst, Survey123 for ArcGIS, and Collector for ArcGIS to collect and analyze data. To collect imagery, they use the Landsat time series, Sentinel, and WorldView 2.

“The Landsat time series lets us analyze the land by season, allowing us to distinguish, for example, between submontane forests [located near the base of a range of mountains] and lowland forests,” said Williams.

Increasing Research Opportunities

Though the Kew Gardens collection of plant life represents more than 95 percent of the known flowering plant genera and over 60 percent of known fungal genera, only 20 percent of the data in this collection is currently available online. To make its digital resources more widely available, the Plants of the World Online (POWO) portal was launched in 2017. Kew Gardens is committed to POWO and other similar initiatives that serve to maximize its impact on science, education, conservation policy, and resource management.

“We are creating POWO as a single point of contact for authoritative plant species information,” said Williams. “Data from POWO will feed directly into conservation prioritization for the delivery of on-the-ground conservation actions by our partners.”

Kew Gardens staff would like to add a drone with lidar and hyperspectral sensors to its technology stack to access 300 to 400 spectral bands. This would allow them to mirror the signature of the plants on the ground to enhance plant identification.

“We hope to introduce ArcGIS Hub in the future, which will give us greater opportunities to share our work with both our in-country partners, as well as our colleagues around the world,” concluded Williams.

Watch “The Story of Kew Gardens in Photographs: Joseph Hooker.”