In fall 2020, students from the Penn State University geodesign program participated in a studio project that focused on revitalizing the city of Utica, New York. During the project, they used ArcGIS technology to develop and present recommendations for the city to implement after the completion of its new hospital.

Penn State University offers geodesign graduate degree and certificate programs that empower the next generation of environmental and urban design experts around the world. It is offered entirely online and designed for working professionals.

Geodesign is a process that leverages the analytical power of GIS technology for a dynamic approach to designing and planning land-based projects that are environmentally, economically, and socially sustainable. Students in the program hail from a variety of academic disciplines and levels of GIS understanding. The goal of the three-year program is to develop students into creative problem solvers who understand and can orchestrate the process of geodesign.

Each year, the program offers students the opportunity to gain hands-on experience at studios in two different settings: urban and rural. The urban design studio presents challenges and complexities that are common to revitalizing a city. In fall 2020, a blended cohort of graduate and undergraduate students collaborated over 14 weeks on a citywide revitalization project for the City of Utica, engendered by the city’s plans to build a new hospital.

“We knew where the hospital location was, and we wanted to know what kind of effects [that it would] have throughout the community. How can we look at the broader picture and opportunities for community growth that this might bring?” said James Sipes, lecturer in geodesign, Penn State Department of Landscape Architecture.

Sipes and his colleague Dan Meehan, Penn State geodesign program manager, believe that it is vital that students not only interact with innovative technology but also think about urban design and planning differently so that they can better use it.

Sipes and Meehan format class projects around the International Geodesign Collaboration (IGC) framework. Using this format allowed students to study three design scenarios for the City of Utica: early adopter, late adopter, and current business-as-usual trajectory.

When these scenarios were visualized, the cumulative impact of implementing planning strategies sooner rather than later was highlighted. To frame the problems or challenges they chose to study, students were asked to estimate the impact of their strategies on the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals. By using the IGC format, students could evaluate scenarios to see whether they positively or negatively affected sustainability goals. “The key point wasn’t to have students reach every goal but to see how the changes they were proposing would impact different levels of sustainability,” said Meehan.

GIS—specifically, ArcGIS Urban—helped students visualize these interconnected challenges and methods for resolving them. “ArcGIS Urban was at the core of what we were doing primarily because it’s one of the few tools we know of that [would allow] us to put in so many different variables, assumptions, and different complexities at that scale and allow us to visualize the impacts,” Sipes said. During the project, students used ArcGIS CityEngine, ArcGIS GeoPlanner, ArcGIS Online, and ArcGIS StoryMaps in addition to ArcGIS Urban.

Some students needed help learning these tools, but Esri staff provided multiple training sessions as well as tech support. Graham Mills, who is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in landscape architecture at Penn State, said support from Esri staff helped him learn the workflows and gain the skills and expertise he needed for his career.

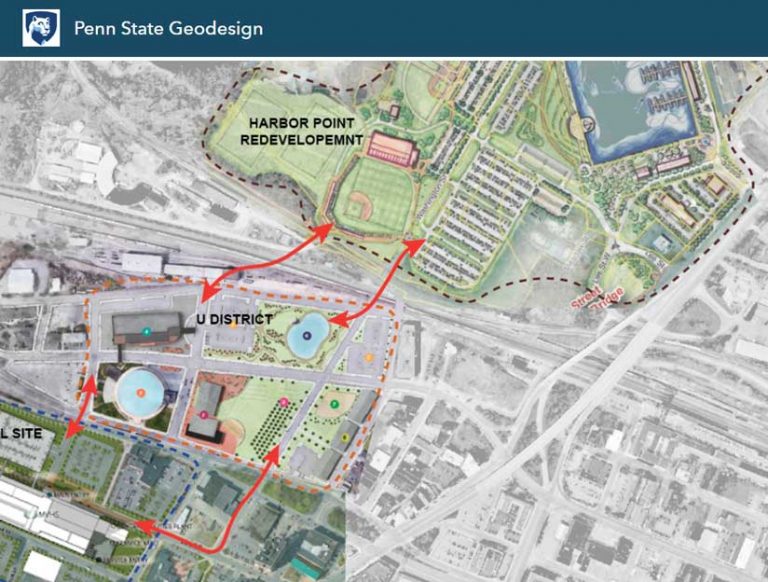

The first half of the project focused on where the hospital would be located—the city’s U-District, an area of downtown for small businesses and entertainment. This portion of the project helped students become familiar with course concepts and tools on a small scale. The students’ analysis included existing and potential business options, ideas to revitalize the historical character of downtown Utica, and opportunities to attract new residents.

“We went from this smaller-sized project to [saying], ‘OK, now that you have reimagined what would happen there, now apply that to an entire city.’ So they had to stop and think about the things they had learned in that first project and apply it on a larger scale,” Sipes said. “We wanted them to think big about how to change the entire city but think in a methodical way on how we can get there.”

A central tenant of the geodesign approach is understanding key stakeholders. As a class, the geodesign students came up with five groups of stakeholders: government, residents, business owners, hospital affiliates, and developers. Acting as stakeholder group representatives, the students researched the needs and goals of each specific group.

They outlined a series of key topics including improving health and wellness with community gardens and agricultural farms, upgrading streets to be more pedestrian friendly, and working with new zoning plans and parcels. One project featured a tree-planting initiative that would focus on vacant land and parking lots to add greenery, enhance air quality, and improve wellness across the city.

“One of the things students did well was that they stopped thinking about singular issues and began to think about multiple issues and overlapping benefits or impacts,” according to Sipes.

At the end of the course, students used ArcGIS Urban to present 3D visualizations and massing models of all the buildings in Utica. They were able to model zoning changes, propose transportation networks and bike lanes, and map areas for parks and gardens. Students presented their findings to geodesign experts and Utica city staff, using ArcGIS StoryMaps to deliver information in a graphical and easy-to-understand format. Student work is also viewable for further learning purposes via the Penn State studio design hub. Through their efforts, students gained significant technical skills and a new way of understanding and applying geodesign.

“As a student who is used to small-scale, site-specific designs, moving toward a city-scale project was a huge challenge,” said Sara Schwartz, who is pursuing a master’s degree in landscape architecture and a geodesign certificate at Penn State. “Overall, these digital tools and their features and storytelling capabilities enhanced my work and experience.”

Looking to the future, Meehan and Sipes hope the geodesign framework becomes more widely used. Geodesign empowers analysis for data-driven decision-making and inspires people to change the way they think about addressing ever-changing, complex issues in the world.