Mapping recovery plans for a climate-resilient forest

In 2018, an enormous California wildfire claimed 85 lives and consumed the entire town of Paradise. Ever since, experts have been devising ways to safeguard against another tragedy and rebuild the forest destroyed by the Camp Fire. Rather than simply replant what was there, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) set out to map a climate-informed restoration plan.

“We want to plant it back better to withstand wildfire and future climate, so the community is not vulnerable like that again,” said Coreen Francis, California and Nevada state forester at the BLM.

During her more than a 20-year forestry career, Francis has seen shifts in forest health from drought, insects, disease, and climate. The pace of change in the forests around Paradise has forced everyone to reexamine their understanding and try to catch up. To create a smart restoration plan, she convened experts to combine their knowledge about the land and forest using GIS to build a sustainable plan.

In less than a decade, several fires had burned across the same area that was devastated by the Camp Fire, which burned 153,336 acres. Since 2018, more megafires have hit, including the North Complex Fire that consumed 318,935 acres in 2020, and the Dixie Fire that burned 963,309 acres in summer 2021. Together, these fires have left few trees untouched in this corner of Northern California.

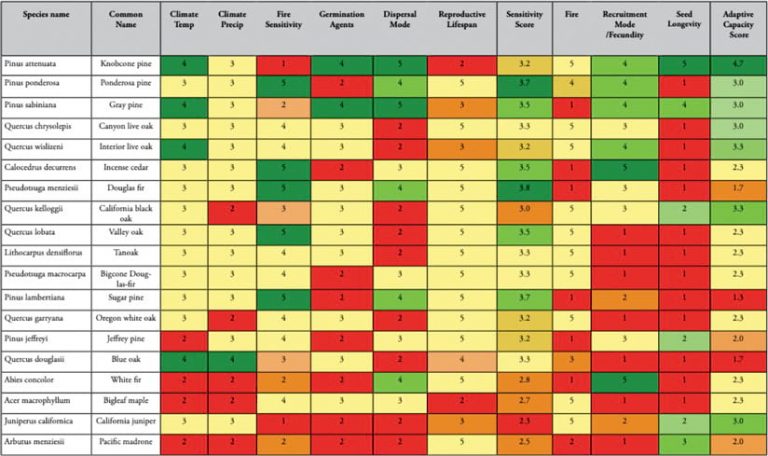

Because the climate has changed, the types of trees that should be used in replanting the area have also changed, according to Austin Rempel, senior manager of reforestation at the nonprofit American Forests. “For instance, sugar pine is everyone’s favorite tree because they grow big and look nice, but climate models say they don’t want to live here anymore. Low-elevation sugar pine is going to be a thing of the past.”

Assisting Tree Migration

Trees can’t just pick up their roots and move, and a natural migration could take centuries. It’s up to foresters to plant for what the forest wants to become, a practice known as “assisted migration.”

“Assisted migration is a no-brainer for our organization, knowing that forests need to adapt,” Rempel said. “In the Camp Fire area, because of its low elevation, it’s quickly turning from dense mixed conifer forest into a place that wants to be more oak and grassland and chaparral and gray pine.”

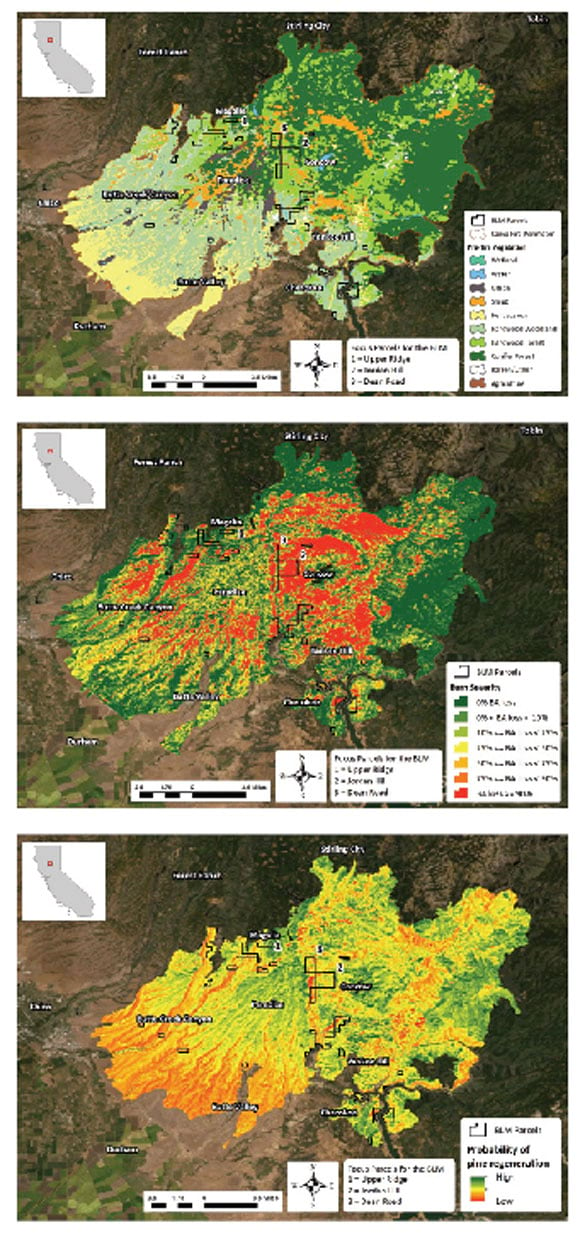

Analysts at American Forests apply models that use spatial analytics to consider species tolerances and soil types, along with climate forecasts about heat and rainfall, to predict what plants will want to live in a place, far into the future.

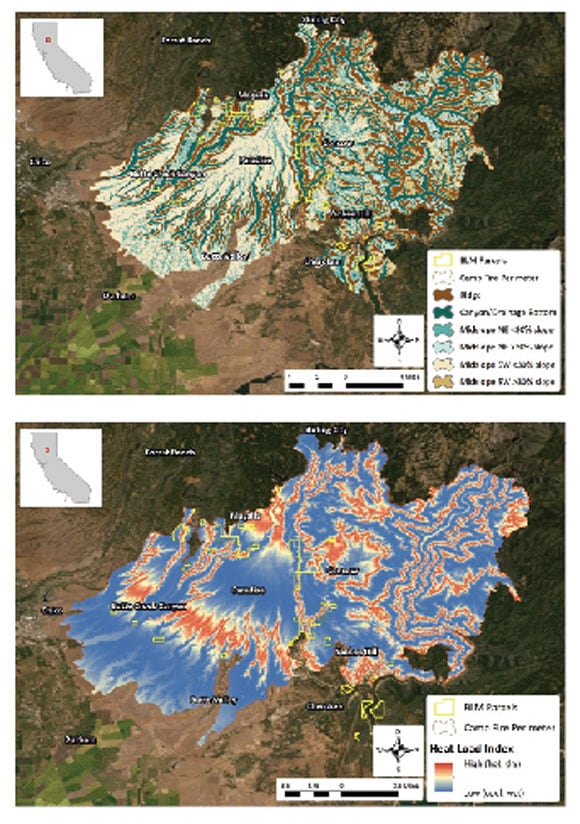

This level of climate action requires a detailed map to understand what exists, the conditions best suited for each plant, and where similar conditions can be found elsewhere. GIS is used to perform this suitability analysis, with predictions that improve with more data.

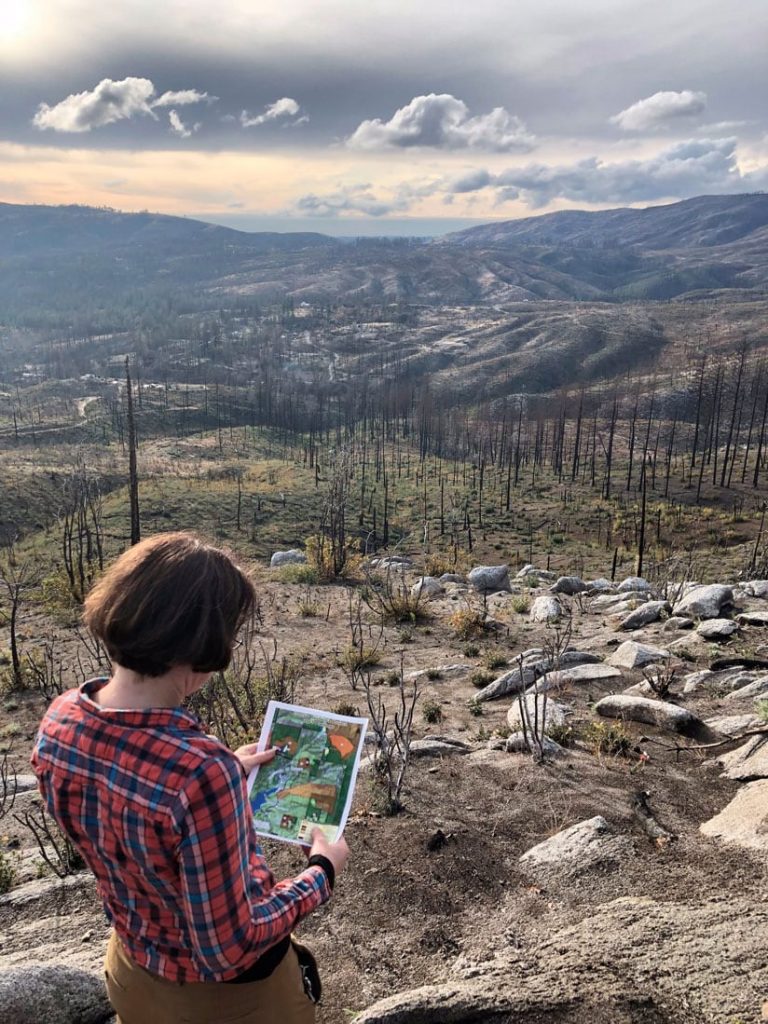

For Francis and other foresters, ArcGIS Online became a repository where they could combine data, plan collaboratively, and view a shared map on portable devices as they roamed the burn scar. Checking the map in the field is called ground truthing, and it provides the opportunity to adjust and add more details.

“Some data we had was wrong,” Francis said. “Being able to see it right there allows us to build knowledge and make our plan a little more accurate. We take scientific concepts, and we look at them on the ground, and then we compare them with what we see on the map,” she said. “We can scroll and look at different layers while we’re walking to inform us of things that we can’t readily see. Knowing the soil type is serpentine, for example, explains why those trees look scrawnier.”

Planting and Planning Simultaneously

In California, the BLM manages 15 million acres. Much of this land is inaccessible to crews replanting trees. The number of seedlings available is limited, so they must be planted carefully where they will thrive.

“Based on capacity, resources, and access, we can only hope to reforest about 10 percent of the Camp Fire burn scar, and that’s if everyone is working together,” Rempel said. “That’s another place where GIS comes in handy, because we have to be extremely strategic and know we’re doing the right things in the right places.”

Much of BLM’s management practices are guided by shared maps. GIS is well suited to landscape-level planning because it contains details on the topography—ridges, rock outcroppings, slopes, water, and valleys. Foresters must consider multiple locational factors that influence seedlings’ success. Among them: north-facing slopes are cooler, south-facing slopes are drier, and valley bottoms have the deepest and best soils.

“Mapping the landscape is a starting point,” Rempel said. “It shows us what the forest should look like and what we should plant there.”

The map pinpoints the places that will be climate stable and ideal for planting specific species.

“We know where trees live now, and we can model the climates they’re comfortable with,” Rempel said. “We can use GIS to map the soil productivity and where trees would be most successful.”

The model and map include ecology, with data to analyze and explore the pieces of the environment that contribute to a tree’s survival. GIS has become a repository of information about the earth’s processes and a way to query and model data so that nature-based solutions can be applied.

“We’ve talked about the concept of island plantings, where you put a diversity of species into a small plot, maybe a quarter of an acre, and grow those in clumps or islands across the landscape,” Francis said. “Eventually trees will produce seed, and the seed will burst into the surrounding area, and it promotes more diversity on the landscape.”

GIS also was used to plan and create natural fire breaks to reduce the intensity of future fires. The map helped speed reforestation by identifying strategic areas for initial planting.

Commons for Collaboration

Multiple stakeholders and participants were involved in making the climate-informed restoration plan. BLM guided the effort with the help of American Forests and participation from the US Forest Service, Plumas National Forest, Butte County Fire Safe Council, Sierra Pacific Industries, and others.

Having a timber company at the table is unusual, but so is what happened to Sierra Pacific’s part of the forest that burned in 2012. Company staff diligently replanted it in hopes of harvesting lumber, and then just six short years later, everything they planted was burned in the Camp Fire. “That was enough for them to say, ‘This is not a place where we can do production forestry anymore,’” Rempel said.

All the stakeholders came to the planning sessions with ideas, maps, and open minds. The evidence was clear: everyone was wasting their time by doing the same things that had been tried before.

“Permaculture ideas—nature-based approaches—are starting to enter into forestry,” Rempel said. “It takes a very long time to convince old-school foresters that this is the way, but it is happening slowly.”

ArcGIS Online became the place where everyone could work and iterate together. For those not familiar with GIS, they could view the maps and agree or disagree with what they were presented.

“The sharing platform was central to our collaborative approach and our climate conversations,” Rempel said. “We had these sessions during different versions of the draft where we got all the land managers and foresters together to go over what they were seeing or if other tricks of the trade should be added to the report.”

Replanting Wisely

The foresters who crafted the Camp Fire restoration plan hope that climate-informed strategies become more common. This approach is practical because it makes the most of limited resources by pinpointing the places where the forest can thrive.

“Many of the climate plans just offer big-picture ideas—about techniques that could be applied,” Francis said. “Our plan takes those large concepts to the ground level. Predictions of what the climate is going to be informs our implementation plan.”

According to research at American Forests, 81 percent of reforestation needed on national forest land is now due to wildfires rather than logging. To replant wisely, new models must factor in future climate.

“This is a recovery plan,” Francis said. “It’s about using the best science to replant.”