On a narrow peninsula in northwest Alaska, about 800 people, predominantly Iñupiat, have made Point Hope one of the longest continuously inhabited settlements in North America.

It’s a “little point with a lot of history,” said Lauren Bosche of the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory. Yet the coastal land where Point Hope was first settled about 2,500 years ago could soon succumb to history itself.

For decades, waves have slowly carved away the northern coast of this narrow piece of land that juts into the Chukchi Sea in the Arctic Ocean. Now, as the region faces a tipping point, Point Hope is increasingly threatened by coastal erosion, thawing permafrost, and rising sea levels.

In early 2020, a three-person team from the public benefit corporation and Esri partner EA Engineering, Science, and Technology, Inc., met with members of the trilateral committee that runs the city—the tribal Village of Point Hope, the municipal government of the City of Point Hope, and the Indigenous-owned Tikiġaq Corporation. The team aimed to use GIS technology—including drone imagery and ArcGIS Pro—to get a clearer picture of how the changing climate impacts Point Hope, and what can be done to mitigate the effects of these changes on the environment and the community.

Disappearing Permafrost Threatens the Arctic Region

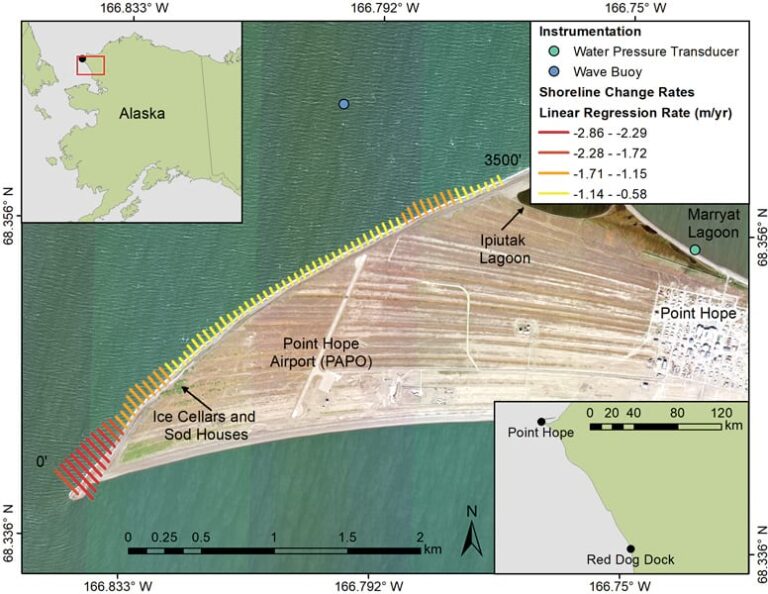

Erosion now consumes 1–2 meters of coastline annually, which has forced Point Hope’s Indigenous residents inland since the 1970s. Recently, erosion has accelerated along parts of the coastline. The ice that normally shelters Point Hope’s shores is not forming early enough in the year to protect the community from violent fall storms.

These changes have also disrupted the Iñupiat people’s ability to hunt wildlife for survival and threatened their cultural heritage.

“There’s an incredible amount of archaeological history that’s already been taken by the ocean,” Bosche said.

Unfortunately, Point Hope’s circumstances aren’t unique. According to the Woodwell Climate Research Center, the last 20 years have seen a seven percent loss of near-surface permafrost due to a warming climate.

The center’s Permafrost Pathways project maps and monitors Arctic warming. Scientists with the center note that permafrost underlies 15 percent of the land in the Northern Hemisphere, and 3.6 million people are at risk if it thaws. Up to 150 billion tons of carbon emissions stored in permafrost could be released into the atmosphere by 2100 as a result. The thaw is also exposing rivers and streams to once-stored minerals that make waterways in parts of Alaska more acidic.

For the Iñupiat people of Point Hope—a place also known as Tikiġaq—the thawing land also threatens their traditional way of life by making it more difficult to store the meat from their hunts of caribou, whales, and seals. “You can’t put a bowhead whale in a chest freezer,” said Ellen Jessup McDermott of EA. And people can’t simply run to the grocery store. “Point Hope is very isolated. It’s very expensive to fly anything in there,” she said.

Native residents rely on siġluaqs—large ice cellars carved into the ground that, for generations, have kept meat cold. The community has recently been losing these cellars to erosion and may have fewer than 10 left. In the few that remain, mold or water has crept inside.

Preserving traditional structures is among several priorities that the community of Point Hope outlined in the North Slope Borough’s 2017 comprehensive plan.

To tackle the many challenges faced by Point Hope residents, the collaborators needed to fill data gaps. They first collected traditional ecological knowledge—learning from the people who not only live there but also survive on what’s there for food.

“They know better than anybody what’s going on where they live,” Jessup McDermott said. “That data is crucial.” She arranged meetings, paying people to participate in formal interviews. Meeting in person was key. And at those meetings, community members were often encouraged to draw what they knew on maps.

One of EA’s certified GIS professionals, Jessica Morrissey, used ArcGIS Pro to help the team view existing conditions, plan fieldwork, and perform spatial analysis. “The maps helped us understand what we saw at the sites and develop a nonverbal, intuitive sense of what’s happening there,” Jessup McDermott said.

As part of the field effort, EA flew drones to capture up-to-date aerial imagery to accurately study the Point Hope shoreline. With ArcGIS Pro, the images were stitched together and geographically tied to spatial analysis results. This allowed the team to visualize the degree of change over time by comparing historical imagery to the new drone imagery.

Engineering with Nature

Bosche’s first site visit was indicative of the challenges that come with living in Point Hope. The journey from Fairbanks, Alaska, where she’s based, involved three flights in a small plane that could carry 12 people at most. There is no road access—just a seven-mile evacuation route to higher ground if needed.

To get a more up-to-date understanding of Point Hope’s coastal erosion, the team used the US Geological Survey’s Digital Shoreline Analysis System, an ArcGIS-created tool designed to calculate shoreline or boundary changes over time. Bosche and USACE Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory staff added new satellite imagery as well as archive satellite images to detect a wider range of change. EA also used photogrammetry to calculate the shoreline change by depicting areas of accretion, areas of erosion, and areas that remain unchanged.

Spatial analysis models revealed that steeper slopes on the beach exacerbated the erosion because of how the shoreline reacted to higher waves.

Ultimately, the community and the collaborators decided to focus on two priorities. To help slow coastal erosion, they plan to build a dynamic revetment—a gravel or cobblestone wall that reshapes the beach face with larger rocks—and a strengthened sand dune built over an armored core.

Progress on the revetment’s design was about 10 percent complete as of mid-2024. To safeguard the subsistence-hunting lifestyle of the Iñupiat, the team members also plan to repair and enhance the traditional underground cold-storage sites. Traditional ecological knowledge informs the careful selection of a siġluaq site based on the size of sediment grains, which determines its success.

“Indigenous people have been working with nature for thousands of years,” Bosche said. “Having a safe community that meets your needs is nothing new.”