In January 2017, the City of Long Beach, California, expanded its geospatial platform with the introduction of DataLB, a public geospatial and open data portal website that helps the public and city staff explore, visualize, download, and use city data. The site implements practices for sharing data with the public, staff, and policy makers that were outlined in the Long Beach Open Data Policy, adopted in 2016.

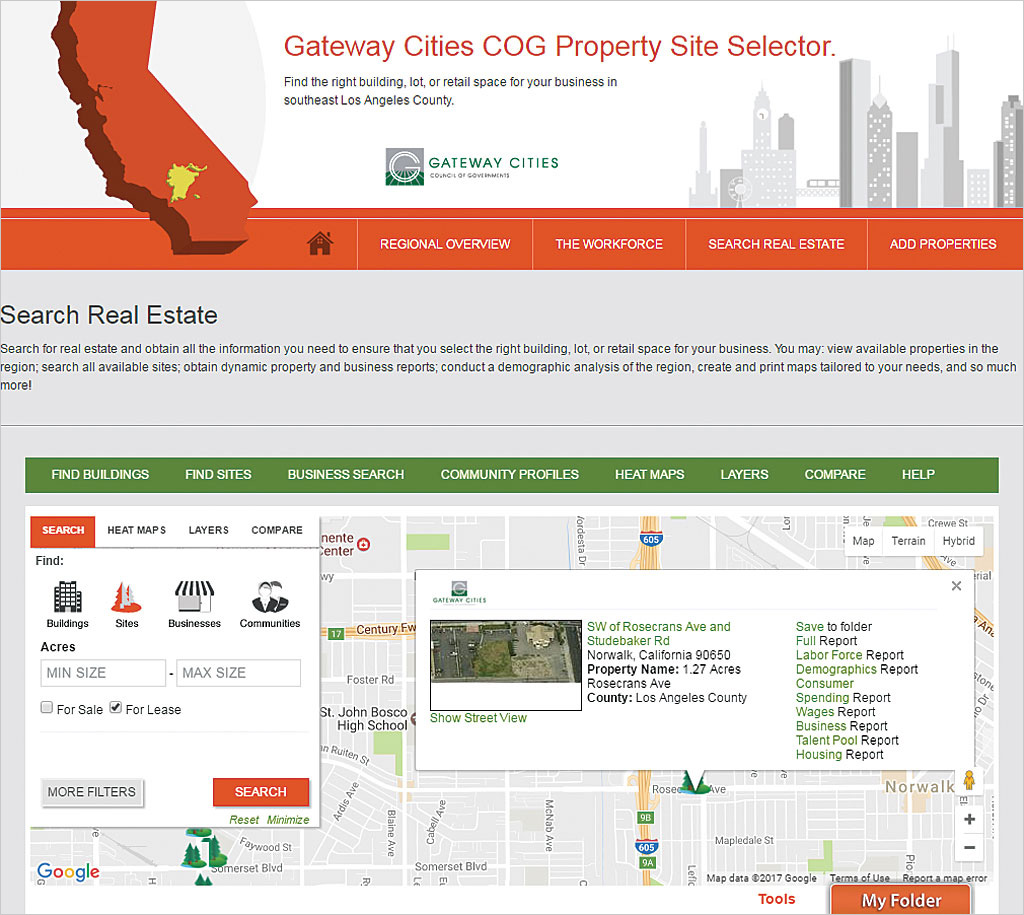

“Long Beach’s DataLB portal is making the vast amount of city data useful for a wider variety of purposes,” said Mayor Robert Garcia in an official statement. “Not only will people be able to use DataLB and new apps available online to chart information like crime rates, but businesses can see the best areas to establish themselves and grow. This is a great tool for the city and the community.”

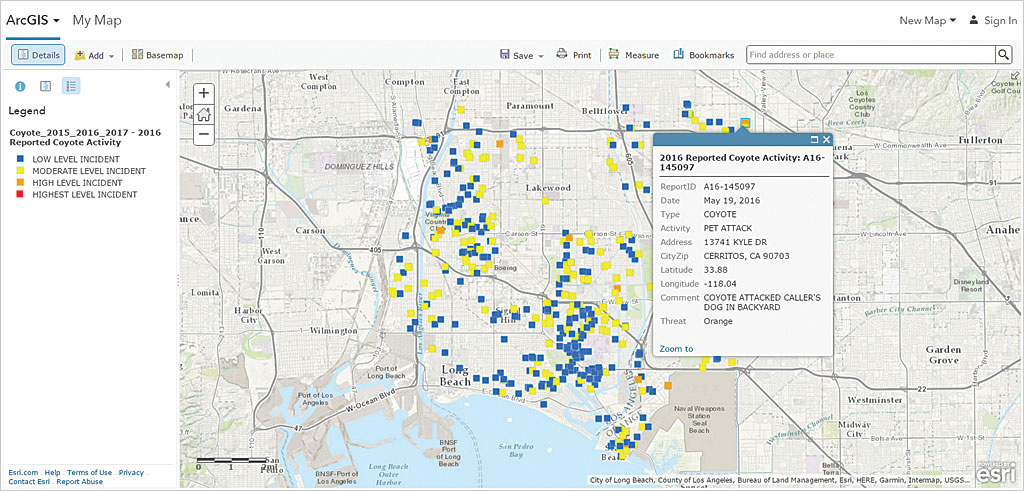

DataLB provides public access to city data that was previously only available to internal staff. The open data site lets anyone map and develop reports on topics of their own choosing ranging from the rate of homelessness in specified areas to business license activity in the city.

More than 100 unique datasets available include local information on community health issues, infrastructure, city spending, business opportunities, planning, parks and recreation, safety, schools, and transportation. All datasets can be viewed or downloaded.

For example, information on the capital improvement projects in fiscal year 2017 funded by Measure A is presented in an Esri Story Maps app. It details how and where the increased revenue will be spent on infrastructure, public safety, parks, community centers, and libraries. The measure, a sales tax increase that was passed by local voters last year, funds a $150 million capital improvement program.

The inception of the Long Beach GIS can be traced to a specific tragedy that occurred on December 1, 1980. A large underground pipeline carrying naphtha, a volatile petroleum liquid, ruptured below the Gale Avenue residential area of Long Beach, shooting flames 70 feet into the air and severely damaging several homes and automobiles. Fortunately, only five people were injured. When firefighters arrived, they noticed a river of fire flowing into a nearby storm drain. They tried to determine the route of the storm drain network to mitigate further destruction, but could not find information on the network.

This event made the city realize the value of a cross-departmental mapping and asset system. Consequently, the city made its first investment in Esri’s GIS technology shortly thereafter. Since that time, the city has used spatially enabled systems extensively, employing ArcGIS across its asset, permit, and utility operations.

In 2014, the city’s newly formed Technology and Innovation Commission proposed a geospatial data hub to make its data more easily available to the public as well as other government and private organizations.

The result was DataLB, the Long Beach implementation of the Esri Hub concept. It is an integrated platform for enterprise collaboration and community engagement that has been customized for the city. The platform organizes and manages services by integrating and analyzing the city’s data feeds throughout its operations. DataLB then provides insights that are accessible organization-wide through an internal enterprise GIS.

With support for a variety of interoperable technologies, DataLB datasets can serve as the basis for virtually unlimited maps and applications that make the city operations data driven. This process is facilitated for nondevelopers through ArcGIS configurable apps and web builder apps and for developers with ArcGIS APIs and SDKs that make it easy to find and connect relevant data to ongoing services and community initiatives.

DataLB includes an open data portal for the public that provides easy access to much of the city’s geospatial and tabular data, as well as policy-related maps and federated data from other government jurisdictions and private organizations. It also includes links to information about current initiatives, which promotes public discussion in the development of lasting solutions that benefit the entire community.

Mayor Garcia also believes that the portal will help the city more easily meet requests from the media and others for public records as required by the California Public Records Act. The portal will allow researchers to search for the information themselves, rather than the slower process of submitting requests through city hall.

A major goal of the portal was including datasets that were of value and interest to the community. To accomplish this, Bryan Sastokas, Long Beach’s chief information officer, led community outreach efforts by hosting forums online and at local universities where residents could discuss what information they would like to have available to them through the portal. Findings indicated that there was great interest in budget, crime, and transportation data as well as information about commerce so that entrepreneurs could do business more easily with the city.

“Providing data online is not a new concept in government,” said Sastokas in the city’s announcement about the project. “But the City of Long Beach wants to drive beyond presenting data online, and our DataLB hub is an innovative approach that allows the public to operationalize data, making it more useful to the community and building on the city’s commitment to transparency.”

In the long term, the city hopes to measure the open data hub’s success against broader issues such as economic development and the way the city uses data to improve services.