In 1986, while Steve Jobs was creating a new workstation computer at NeXT and Dr. Leonard Baily was pioneering infant heart transplants at Loma Linda University Medical Center, Brenda L. Carter was 21 and on the cusp of a new adventure: computer mapping.

She and her friend had intended to go to medical school together after attending South Carolina State University. However, the tragic death of her friend altered Carter’s plans to become a doctor.

Instead of going to medical school, she took a job in the Lexington County Planning Department in South Carolina as an addressing specialist for the new E-911 system. “They needed an addressing person to assign addresses and help with road naming,” she said.

Carter’s interest in medicine was soon supplanted by a passion for computers, mapping, and planning. “I could read the maps very well, and I picked up everything they would teach me,” she said. “And that was simply because I was so interested in the [planning] field. I was like a sponge.” When Lexington County launched its first GIS in December 1988, Carter was selected for training on ARC/INFO 4.0, the new GIS software from Esri.

“The minute that I started with that software, I was hooked,” said Carter, now 52 and the GIS manager for the Planning and Development Services Department (PDS) for Richland County, South Carolina. “It piqued my curiosity. The software helps you to provide important information in the decision-making process.”

In the early 1990s, GIS helped her decide where a fire station should be built that would serve a community that included a new housing development. “GIS helped resolve the issue successfully using location allocation,” Carter recalled. From that point, Carter had a new duty—finding the best locations for new fire stations in Lexington County.

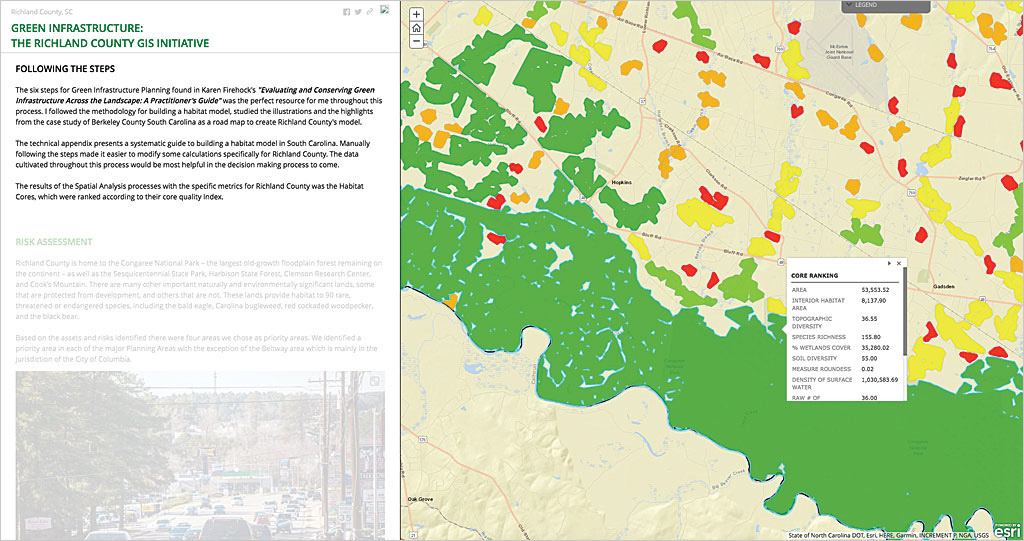

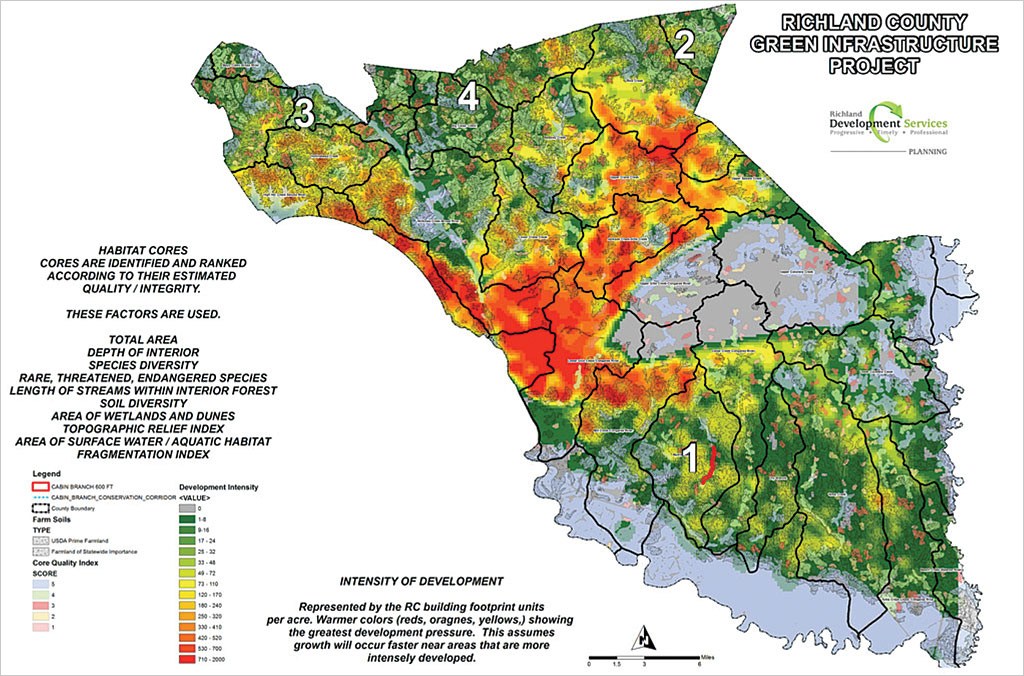

Carter still answers important questions using Esri software. In 2016, she used ArcGIS for Desktop and the ArcGIS Spatial Analyst extension to create a green infrastructure plan for Richland County. “Richland County is growing. It’s hustling and bustling,” said Carter. “[But] we do want smart development.” The Richland County GIS Initiative aims to protect environmentally sensitive areas of the county by acquiring land from property owners using conservation easements.

Carter made an Esri Story Map Journal app, “Green Infrastructure: The Richland County GIS Initiative,” that summarizes the project. (Read more about this plan in “Green Infrastructure Plan Fuels Smarter Growth in Richland County,” an article in the winter 2017 issue of ArcNews.)

The AML Queen

Carter got her start in GIS in the early years of the computer mapping revolution. Esri released its first version of ARC/INFO in 1982. Lexington County adopted the software in 1989, just three years after Carter began doing addressing work.

The county only had one problem. “When we started, we had no geographic data. None. No layers,” she said. “We literally had to create the first basemaps.”

To do that, Carter had to learn how to code. Carter learned ARC Macro Language (AML), the scripting language that Esri created in 1986, to automate tasks and create custom applications in ARC/INFO. “This is old-school stuff,” she said.

How did Lexington County get its data for the basemaps? “We digitized our road centerline sheets over our [orthoimagery],” she said. “I wrote an AML for everything we needed to do.” They digitized more than 10,000 parcels before the county assessor’s office contracted the project out.

Her colleagues were supportive, Carter said. “I worked with some great people,” she said. “My director at the time, Charlie Compton, allowed me all the time in the world to learn the software and read the manuals so I knew what to do. Cheryl Matheny was there to bounce ideas off of, and my dear friend John Kludo taught me the finer things of AML coding.”

After the data edits were completed in ARC/INFO, the basemaps took shape. Once the 567 individual maps were digitized, Carter wrote an AML script that brought each individual file, point, line and polygon together. “Boom, we had a countywide road centerline layer, we had a countywide easement layer, and so on,” said Carter.

Map production took off. “We printed out everything from subdivision maps and zoning maps to road centerline maps to easement maps to tax maps and special project maps,” she said. “You name it, we printed it.” Carter and her coworkers completed several projects.

By 1996, Carter was known as “the AML Queen of Lexington County.” She even won that year’s AML Short Cut Award in a contest that Esri sponsored. Her winning Freeze and Thaw scripts saved and restored map production settings in ARC/INFO. Her short scripts prevented settings from being lost and printing disrupted when staff shut down their computers at night. “If you typed freeze, it would remember all your settings. When you came in the next morning and turned on your computer and typed thaw, it would bring all your settings back up and start you back right where you were,” Carter explained.

She Has Rural Roots

Today Carter is a certified GIS professional (GISP). She manages a small GIS and addressing team at Planning and Development Service in Columbia, South Carolina, the county seat for Richland County. However, her office is only about 34 miles from where she was raised in Batesburg-Leesville, a close-knit community with a population of about 5,400 people.

She grew up with four brothers and one sister. Carter was always interested in science and the outdoors. “My father liked fishing, and I loved to go, too,” she said. As a child, Carter loved nothing better than going down to a local lake or stream with a fishing rod in hand. She would bait her hook, cast out her line, and wait. “I loved to go fishing,” she said. “The worms didn’t bother me. My sister—that’s another story,” she said, laughing. There was something relaxing about being on the water and waiting for the big one,” Carter said.

Her father also taught her spatial awareness. He worked for a long time as a truck driver and always impressed upon his daughter that she should be aware of her surroundings. “When I was younger, I didn’t read a map in the car. But when we would travel, my Dad would always say, ‘Read the signs so when you go somewhere, you will know how to get back out.’ So I was always about location, location, location,” she said. “To this day, if I go somewhere once, I can go back again.”

Carter said she later received formal training in map reading in a Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) class at South Carolina State University. This training served her well when she applied to be an addressing specialist for Lexington County.

“One of the things you had to do during the interview was to find some locations on a tax map, so you had to be able to read a map.” she said. “I completed that part so fast, it was like a no-brainer for me, but I was told so many others couldn’t do it.”

Keeping It Rich Land

Carter was hired as the GIS manager at Richland County PDS in 2000. In the last 16 years, GIS technology has changed dramatically. ARC/INFO is long gone. So is AML.

While others might resist change, Carter is all for it. She said she always advocates for the use of the best, updated technology that will help the planning department do its job more efficiently. Recently she has been showing the department staff the advantages of Web GIS, including creating configurable apps using ArcGIS Online. She’s also planning to make more Esri Story Maps apps, which are good tools for sharing information with government officials and the public.

“Story maps are easy to use because they help ordinary people visualize important data in an intuitive format,” said Carter. “Story maps provide a nongeographic dimension to the data. If I show you a map, you may soon forget what that was all about, but if I tell you a story, you are more likely to remember what the story was about. Telling stories about data is the way to grab and keep people’s attention.”

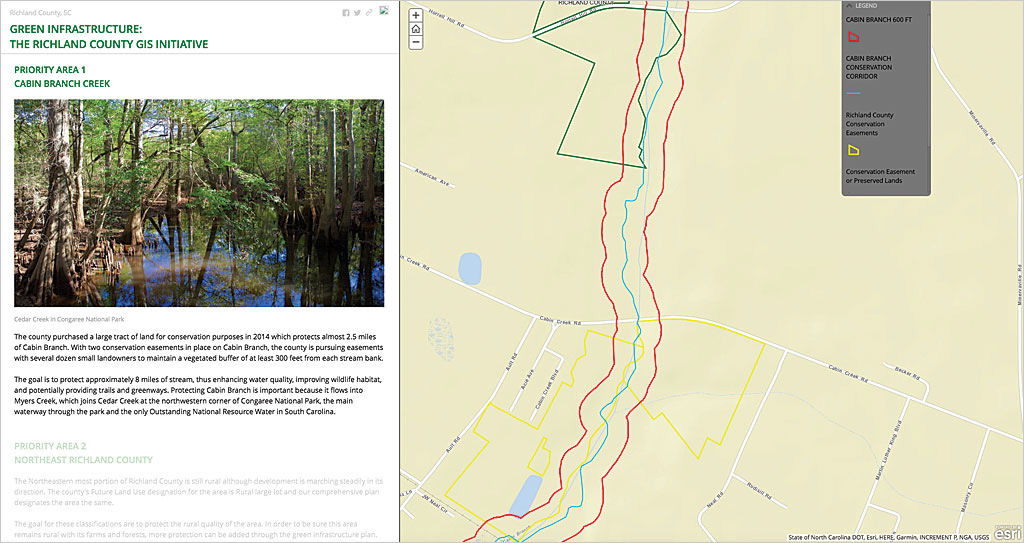

Carter gave a presentation on the green infrastructure project during the 2017 Geodesign Summit at Esri headquarters in Redlands, California, in January. She showed the audience her Green Infrastructure: The Richland County GIS Initiativestory map, which outlines the plan’s goals and displays interactive maps that show the results of her habitat analyses. The story map lists four priority areas for future conservation, including Cabin Branch Creek south of Columbia, where Richland County has already bought land for preservation and plans to acquire easements from several property owners. The green infrastructure initiative currently serves as the only planning guideline for future development within the county.

Carter was assigned to the GIS portion of the project in the wake of major flooding that wracked South Carolina in October 2015. Hurricane Joaquin brought torrential rains to the state. Columbia alone was doused with more than 12 inches of rain, while other parts of the state received more than 20 inches. About 160,000 homes sustained damage.

Earthen dams that people had built along streams to create ponds broke loose after days of rain, sending water downstream to low-lying areas. “You had little creeks that became big rivers that washed out roads and railroad trestles,” Carter said. “Bridges were completely washed out, and we had road closures.”

The damage sustained by homes built in the floodplains was the impetus for the green infrastructure project. Its goal—where possible—is to leave more areas along streams and in floodplains undeveloped to reduce the chances of flood damage to houses and infrastructure in the future.

In Richland County, named for its fertile soil that yielded crops such as indigo and cotton, agriculture has given way to development in recent years. Carter hopes the green infrastructure project will help South Carolina maintain some of the rural character that marked her childhood—a childhood in which she fished, rode horses, and played in the woods.

“We want to grow,” she said, “but we don’t want to destroy our natural resources while we are growing