The author, Rob Davies, is the director of Habitat Info Ltd., a global technology company that specializes in the capture, management, analysis, and distribution of spatial data. In 2012, Habitat Info launched a charitable citizen science project to collect data on the conservation status of African raptors to determine how much habitat space was left for them.

Initially, the African Raptor Databank (ARDB) met with opposition from critics who said collecting the status of raptors across Africa could not be done because Africa was too big. They urged Habitat Info to limit efforts to a region of Africa at most, focusing on protected areas and countries. However, raptors range freely, and many make annual pilgrimages across and between continents to breed and winter. In addition, it is funny that people often believe a smaller study area is less work to map in GIS. It’s not.

Starting with Africa

Two people and one organization stood out for their support of Habitat Info’s holistic approach: Dr. Rick Watson and Dr. Munir Virani of The Peregrine Fund. [The Peregrine Fund is a science-based, project-driven conservation organization based in Boise, Idaho.] Watson and Virani, through their organization, have done much good work for raptors around the world. They supported ARDB from the start by generously sponsoring ARDB’s Esri software. Esri provided ARDB with a nonprofit grant scheme that helped launch the project.

With access to ArcGIS Server, Habitat Info could pull in data from mobile phones from pretty much anywhere across the continent because in Africa almost everyone carries a mobile phone. First Virani, then later Darcy Ogada, coordinated the database for East Africa. Database coordination was done by Andre Botha in southern Africa; by Clive Barlow, Dr. Joost Brouwer and Dr. Ralph Buij in Central and West Africa; and by Dr. Hichem Azafzaf in North Africa. With the right team in place, data flowed in from hundreds of keen-eyed raptor observers across Africa.

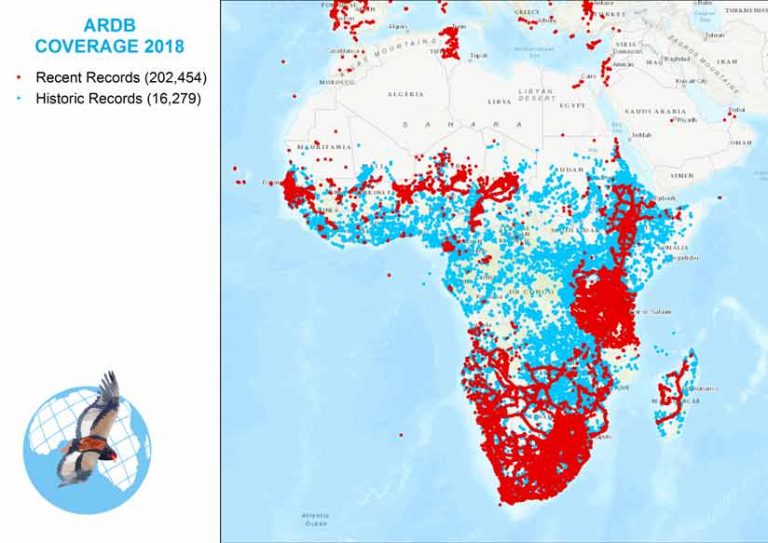

After five years, ARDB had more than 200,000 sightings of African raptors. At the end of this data collection period, the author travelled to Boise to show the results to members of The Peregrine Fund and thank them for believing in the project when others did not. Their response was, “Why stop at Africa? Let’s go global!”

Going Global

ARDB then entered a new phase. Thanks largely to Chris McClure, Leah Dunn, Paul Spurling, and Brett Sebring, ARDB has become fully integrated with The Peregrine Fund’s existing Global Raptor Impact Network (GRIN) and is hosted by a large database on the Amazon cloud. The Peregrine Fund’s approach has facilitated the successful reinstatement of many locally extinct raptors around the world.

While overcoming the technological challenges of gathering and collating data on raptors, there was convergent evolution in the quality and resolution of global, and especially Africa-wide, environmental datasets. The digital elevation models (DEMs), which revealed mountainous Black Eagle habitat; the global forest cover datasets, which represented Crowned Eagle habitat; and landcover, climate, and human population impact datasets. All showed improvement by orders of magnitude. These datasets were available at resolutions of 1 kilometer or even 300 meters, which were scales ecologically meaningful to individual pairs of raptors finding territories across Africa.

Dr. Corinne Kendall joined the team of coordinators towards the end of data gathering and she added an entirely new type of data on African raptors—movement data. This data from satellites and GPS tags fitted to wild birds revealed extraordinary behaviours and filled many gaps in our knowledge about where these birds travel. This data created a much more complete picture of raptors, one that could only have been dreamed of a decade earlier.

The project initially started with an Enterprise Geodatabase hosted on a little server housed in Habitat Info’s office. It benefited enormously from the enthusiasm of Habitat Info staff members Andrew Rayner, Tim Wroblewski, and Simon Trice, who worked industriously with interns Sarah Wigley and Zoey Taylor to build the database.

Battling with the many different formats in which data was submitted made the team long for a method that would let observers add their own data. Rayner developed a pro forma spreadsheet for bulk loading existing data while ensuring data quality and verification, but the challenge of automating the addition of new data remained.

Early attempts to solve this problem with mobile technology made use of ArcPAD on an HP iPaq. Subsequently, Habitat Info staff member Rayner successfully applied his clear vision and programming skills to fulfill Habitat Info’s elaborate requests to produce an intuitive, state-of-the-art mobile recording app for logging almost all aspects of raptors and their behaviour.

These efforts attracted a lot of interest, including development support from Kurt Eckerstrom, Nick Williams, and the Convention on Migratory Species. Habitat Info is most grateful for their help.

The app allows both professional and citizen scientists to conduct multiple survey types with just a single tap of the screen. Simple sightings can be entered, and a wide array of morphological and behavior data appended. The app avoids tedious data entry by securely uploading data directly to the GRIN database.

With the GRIN app developed and available, Habitat Info is turning its attention back to Africa and intends to gather support to publish the ARDB and produce a hardcopy of the Conservation Atlas for African Birds of Prey.

The Value of Vultures

One group of raptors brought the need for the ARDB into acute relief—Africa’s vultures. Vulture populations have been spiralling downward in the last couple of decades.

The decline is clearly caused by the illegal use of poison. Poachers in southern Africa lace elephant carcasses with poison to eliminate tell-tale soaring birds that give away the location of their crimes. A 40 percent decline in vulture populations has been attributed to poisoned carcasses. In Eastern Africa, a 60 percent decline in the vulture population was caused mainly by farmers who were trying to poison predators that were killing their livestock. A single carcass laced with poison can easily kill all the vultures in the surrounding area. This practice has been causing local extinctions.

In West Africa, a 90 percent decrease in vulture populations was linked to the illegal trade in vulture body parts. These parts are used in traditional medicine and play a part in superstitious practices used to predict soccer scores.

With such a precipitous decline, something needed to be done quickly. Buij, with support mainly from the Dutch government, stepped in and coordinated a project that pulled together everything then known about vultures and the threats to them. This project was the first significant use of ARDB and the clearest example of why these knowledge management systems are needed to enable more efficient conservation.

Sightings, habitat suitability models, and the movement patterns of vultures helped identify the most important habitat strongholds for vultures across Africa. This knowledge has helped conservationists focus efforts on the most important places instead of spreading efforts too widely across the vast continent. The culmination of the project is a series of maps and an educational poster to promote awareness and understanding of the threats to vultures.

The decimation of the vulture populations from the Indian subcontinent has been attributed to the use of diclofenac, an anti-inflammatory drug given to cattle beginning in the 1990s. The decrease in vultures led to an increase in feral dogs that has been associated with an increased incidence of rabies and other diseases, according to an article published in the scientific journal Nature in 2004.

Strongholds for vultures are also strongholds for most other wildlife, especially vulnerable large carnivore populations, such as lions and wild dogs, as well as a host of other species that are less visible than raptors and consequently, less capable of signalling that something is wrong in their habitats.

An abundance and diversity of raptors invariably signals a largely undisturbed ecosystem supporting an abundance of other wildlife.

Ultimately, the Global Raptor Impact Network App was funded by The Peregrine Fund in conjunction with GRIN using Esri’s ArcGIS Mobile SDK for Android and iOS. It is provided by The Peregrine Fund as a free tool for conducting raptor research that works happily offline—which is essential when working in remote parts of Africa—and seamlessly uploads to the enterprise database when the device becomes connected to the internet.

The Role of Raptors in Protecting Ecosystems

The loss of vultures and other raptors from Africa may be far more consequential than the loss of elephants, rhinos, and other higher-profile species that monopolize popular attention and funding. Raptors are indicators of environmental health. They are highly effective as “canaries in the coal mine” that provide early warning when vital earth support systems are threatened.

As notable raptor researcher Professor Ian Newton put it, “An abundance and diversity of raptors invariably signals a largely undisturbed ecosystem supporting an abundance of other wildlife.”

For more information, contact Rob Davies at rob.davies@habitatinfo.com.

Acknowledgment

A word of thanks to Esri and its associates. Whenever I have approached Esri for help with my many and varied conservation projects around the world, it has always helped creatively. I guess the culture that has arisen from a company, originally called Environmental Systems Research Institute, and the people who built it have great empathy for the environment. Thank you to Esri for helping raptors and other wildlife. It is very much appreciated.