Compared to the Esri User Conference—a big, bustling event about all things GIS that draws about 18,000 attendees annually—the Geodesign Summit is a small, understated affair. At this year’s summit, held February 25–27, 2019, at Esri headquarters in Redlands, California, 225 people from 18 countries congregated to share geodesign projects and learn about geodesign concepts, methods, and technology.

While some commonalities exist between geodesign and GIS, there are differences, too. Geodesign combines the art of design, the science of geography, and input from stakeholders to find the most suitable, sustainable, and environmentally friendly options for using space. That may be space for wildlife conservation, agriculture, development, transportation, and marine protected areas—to name a few examples.

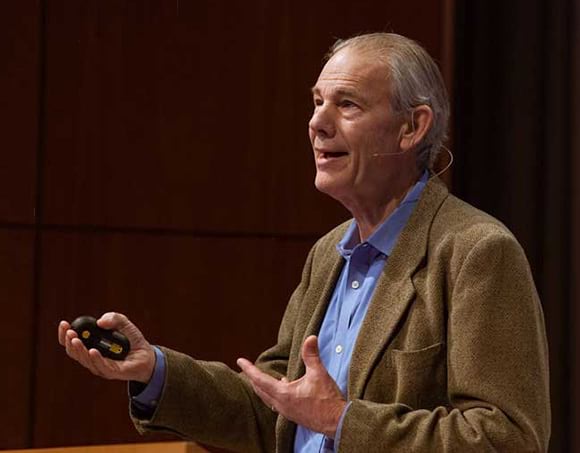

Esri president Jack Dangermond, who earned a master’s degree in landscape architecture from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, has been a strong proponent of geodesign for years, helping organize the first Geodesign Summit in 2009. In marking the event’s tenth anniversary, Dangermond said the practice is finally taking root in academia, urban planning, conservation, some parts of government, and other areas.

“This idea of geodesign is becoming a movement, [though] it’s subtle and in the background,” he said in opening the 2019 Geodesign Summit. According to Dangermond, geodesign is part and parcel of the digital transformation that includes big data, artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things (IoT), and Web GIS. He urged audience members—many of whom were design or GIS professionals—to put their creative and technical talents to work to take on big issues such as climate change, sustainable development, and conservation, especially as the world population grows and resources become strained.

“The pace of change is accelerating at an exponential rate of growth. In some ways, it’s threatening our natural world,” Dangermond said. “We may not make it. That’s why this meeting is so important. We need to grasp the problem and formulate action. You as human beings are the treasures here and not the technology. But we need to embrace digital transformation and leverage geospatial science to do geodesign.”

While the creative aspect of geodesign is important, it’s only one side of the coin. The other is what Dangermond calls the “geospatial infrastructure,” meaning the content, services, and the GIS tools for mapping. Bringing geo together with design opens possibilities. “Applying the power of digital geography [helps us] envision what’s possible, whether it’s creating sustainable developments, making cities smarter, designing with nature in mind, or protecting biodiversity,” Dangermond said. “I’m all about leveraging the power of geography to manage the world better and to make a difference.”

Designing Florida’s Wildlife Corridor

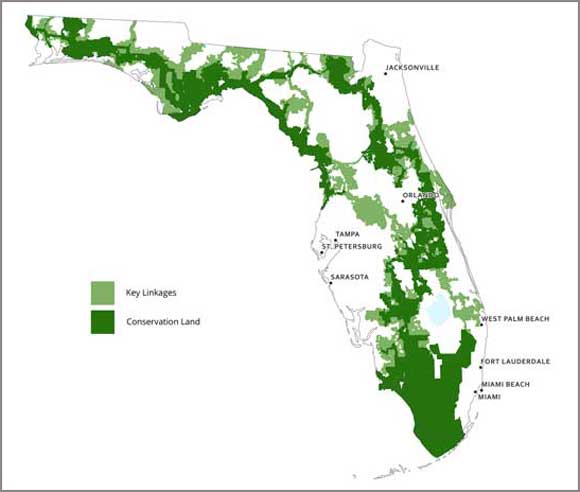

One person who is making a big difference is Carlton Ward Jr., an eighth-generation Floridian and conservation photographer whose work has been published in magazines such as National Geographic, Smithsonian, and Audubon. Ward founded Florida Wildlife Corridor, an organization that aims to protect, connect, and restore land and waterways that have been identified as conservation priorities in a green infrastructure network throughout Florida.

n his Keynote Address at the Geodesign Summit, Ward talked about how he uses photographs, videos, and maps to tell stories about what he calls “wild Florida,” the ever-shrinking habitat for animals like the Florida panthers, black bears, bobcats, alligators, and birds such as cormorants.

“This is my Florida,” he said as he showed photos of cowboys, oystermen, and Florida panthers. Only about 200 Florida panthers roam the state. “Wild Florida is still there, but it’s hidden in plain sight, unseen, overlooked, or forgotten by most of Florida’s 21 million residents and 125 million annual visitors.”

“Wild Florida is still there, but it’s hidden in plain sight, unseen, overlooked, or forgotten by most of Florida’s 21 million residents and 125 million annual visitors.”

Ward comes from a family of cattle ranchers and politicians. His great-grandfather, Doyle E. Carlton, was Florida’s twenty-fifth governor. And his family’s cattle ranch serves as a habitat for panthers and other wildlife. Rather than go into ranching or politics, Ward became a conservation photographer. He has traveled to Gabon in Africa to study biological diversity and photograph 400 different species of animals and plants. “Working in Gabon gave me an appreciation for intact wilderness,” he said.Eventually, however, wild Florida drew him home.

Ward, who has a master’s degree in ecology, has kayaked, hiked, and ridden horses during two 1,000-mile expeditions throughout the state, all the while photographing the wildlife that roam and the people who work the land he holds dear. Ward has captured spellbinding photographs of panthers and black bears as they travel through protected areas, cattle ranches, orange groves, or other undeveloped private and public lands. “I can help the panther take his own picture,” said Ward, who played a video of how he sets up the camera traps and then leaves his equipment behind in remote places.

During his presentation, Ward also displayed a map that traced the 500-mile journey of a bear named M34. The bear, fitted with a GPS tracking collar, traveled through south-central Florida over a two-month period. Although the animal was ultimately stopped and turned around by Interstate 4 and big housing developments nearby, Ward said the bear was able to travel that far thanks to a network of working farms and ranches that keep the public lands connected.

Ward says Florida’s population increases, in net, by about 1,000 people a day. Housing for these new arrivals often gobbles up land. Ward says his organization’s goal is to help grow his state’s wildlife corridors and keep these areas intact so wildlife can move about unhindered and unhurt. Endangered panthers have been struck and killed by vehicles. About 30 panthers were killed in 2018.

On the brighter side, wildlife crossings have been built under some highways, allowing animals like panthers and black bears to avoid the onslaught of cars and trucks. In November 2016, Ward said a female panther traveled to an area north of Caloosahatchee River—something that had not been documented since the early 1970s. This showed a northward expansion of the panther’s breeding habitat.

In a panel discussion after his talk, Ward told Dangermond and members of the audience that using imagery and a GIS framework can guide conservation stakeholders as they continue to expand the wildlife corridor. Ward is currently working on a conservation photography project called Path of the Panther. The project collects donations to help elevate the story of the Florida panther and critical habitat needed to help save wild Florida.

Time is short, said Ward. Currently about nine million acres of the Florida Wildlife Corridor are protected, and there’s an opportunity to conserve nearly seven million additional acres. “If we don’t take action in the next decade, we are going to have some irreversible [environmental] damage,” he said. “I am excited about the promise of the geospatial cloud to help create a universal framework and common language for land conservation and chart the course for protecting 30 percent of the planet by 2030 on the way to ultimately protecting half the planet.”

Geodesign in Action

During the three-day summit, dozens of presenters at the Geodesign Summit shared compelling stories of how they use geodesign and maps to make better-informed decisions, often about land-use choices. They included Devin J. Lavigne, a principal and cofounder of the consulting firm and Esri partner Houseal Lavigne Associates, which specializes in urban design, community planning, and economic development. He showed how Houseal Lavigne Associates is using Esri’s community engagement software, ArcGIS Hub, and one of Esri’s data collection solutions, Survey123 for ArcGIS, to gather feedback about the master plan for El Paso County, Colorado, from the people who live there.

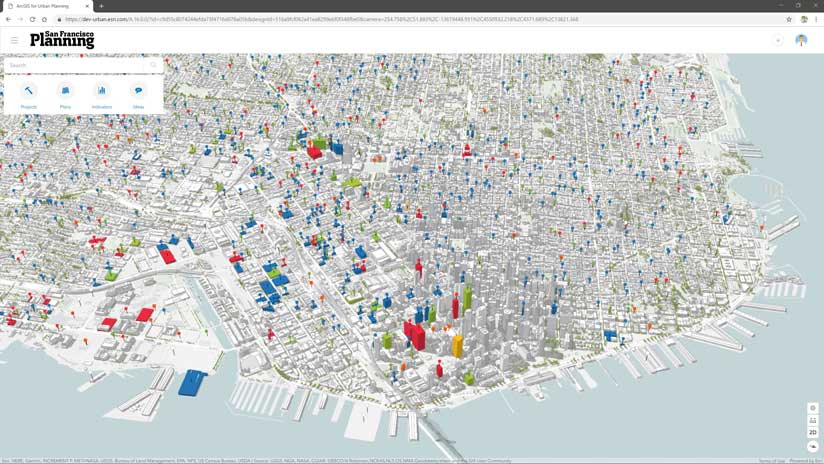

ArcGIS Urban, a web-based GIS solution designed for urban planners that will be released this summer, was demonstrated at the Geodesign Summit. It lets planners visualize a digital twin of their community and keeps all citywide plans and projects in one place. With ArcGIS Urban, planners can create, manage, and share plans; visualize current projects; see zoning regulations in 3D; compare design scenarios; analyze the impact of their plans based on a set of built-in indicators; and engage with the public. Stakeholders, whether inside or outside of government, can share ideas about or weigh in on plans using the comment section.

Ken Schmidt, GIS administrator at the City and County of Honolulu, Hawaii, talked about doing geodesign with ArcGIS Urban. While still in development by Esri, the software is being put through its paces by several early adopters. Honolulu is using ArcGIS Urban to analyze how zoning changes in Honolulu could create opportunities for additional housing in an already highly urbanized area. Schmidt demonstrated the impact of adding five-story walk-up apartments in the Moiliili neighborhood compared to the currently permitted three-story walk-up apartments.

Mapping Land for People

According to Will Rogers Jr., president emeritus of The Trust for Public Land (TPL), the mission statement for TPL emphasizes creating parks and protecting land for the people rather than protecting land and nature from the people. Since 1972, the nonprofit organization has worked on projects that have set aside more than 3.3 million acres for protection throughout the United States and has finished more than 5,400 parks and other conservation-related projects.

Maps have long been part of the equation to pinpoint areas that needed to be protected and decide which communities were most in need of parks. “Nonprofits like TPL exist to make a difference, and GIS has helped [the organization] make a bigger difference,” said Rogers, during a talk he gave at the Geodesign Summit. “From day one, maps told the story—and Esri was a key and longtime partner and a supporter of our work.”

As GIS technology became more sophisticated, TPL brought Breece Robertson aboard in 2001 to lead its GIS program and develop mapping tools. She’s now vice president and chief research and innovation officer at the organization. TPL’s tools quickly became more advanced. The organization can use GIS and demographic data to find out where parks are needed and who does not have access to them, Rogers said. For example, TPL found out that two-thirds of the children living in the city of Los Angeles were not living within a 10-minute walk (a half-mile radius) from a park.

TPL used GIS to help develop the ParkScore ranking system to evaluate how well cities are doing in providing easy access, amenities, acreage, and investment in parks for its residents. Currently, Los Angeles has a ParkScore ranking of 66 out of 100 for large American cities, while Minneapolis, Minnesota, ranks No. 1. (See “Website Helps Discover, Explore, and Improve US City Parks” in the winter 2012–2013 issue of ArcNews.)

None of this would have been possible without GIS and geodesign

The next Geodesign Summit will be held February 24–27, 2020 preceded by the International Geodesign Collaboration (IGC) held February 22–24, 2020. Both events will be held at Esri headquarters in Redlands, California.