Governance is among the primary levers used by GIS managers in their never-ending quest to improve the quality of geospatial data, content, and solutions provided to their organizations.

GIS governance offers a formal structure for making and managing decisions about the long-term direction of a geospatial program and a mechanism to handle the day-to-day issues that inevitably arise when managing a complex enterprise system. When done well, governance empowers managers with the oversight and authority required to ensure their organization’s geospatial program meets its mandate.

Over the past several years, my colleagues at Esri Canada and I have worked with various organizations on their geospatial governance models—including local and regional government agencies and organizations from heavy industry and the private sector. The lessons from those engagements have proved invaluable in helping us formulate and refine our thinking on the topic.

We’ve taken steps to synthesize this knowledge into frameworks that help others with their governance endeavors. I’m confident that these efforts have helped bring greater awareness to the topic of governance and its relevance to the geospatial industry.

However, despite those efforts—or perhaps because of them—governance remains a difficult topic. Conceptually, governance is challenging because of the complexity and sheer scope of processes to consider when attempting to devise an appropriate governance model. In practice, it’s even more difficult because those with a stake in the geospatial program must be aligned and agreeable whether they are stakeholders in data or systems ownership or in the long-term direction of the program itself.

Studies have shown that organizations often leave geospatial governance to other domains like IT governance (if they do it at all). However—for better or worse—you need geospatial governance. A geospatial program of any significant size, at some point, will need clarity about who has rights to what and who makes those decisions. The trick is to figure out what aspects of your program to focus on and which controls you need to implement.

To help make this process easier, we’ve taken our previous frameworks and put together a simplified version that distills geogovernance into a set of generalized components. The goal is to provide a tool that helps you identify what you’re missing and where you need to focus on to develop a governance model that works for you.

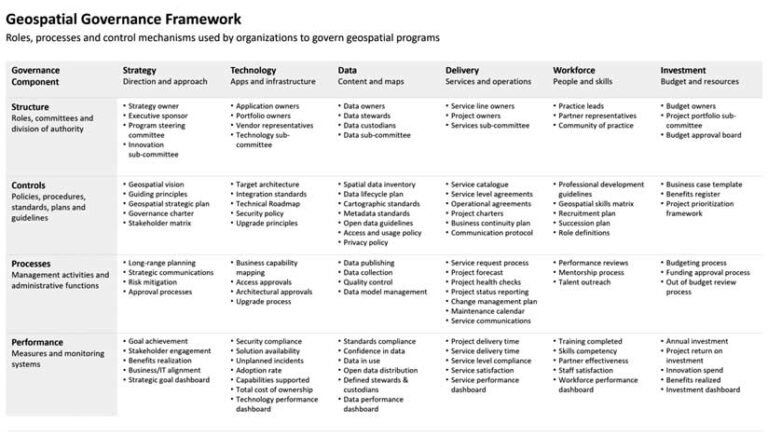

The framework covers six foundational domains, each representing a defining aspect of your geospatial program. These are areas requiring focused attention and careful decision-making. I’ve discussed these domains at length in previous articles. In summary, these domains cover areas, as categorized in Table 1, that relate to direction setting and funding (Strategy and Investment), geospatial technology and content (Technology and Data), and services and human resources (Delivery and Workforce).

The purpose of your governance model is to establish a sufficient level of oversight across each domain to ensure your geospatial program reaches its objectives. That means determining who is accountable for the critical decisions across each domain and the controls, processes, and measures that create the desired system of control. In our framework, this system of control is divided into four major components: structure, controls, processes, and performance.

Structure

The structure of your governance model determines the division of authority across each of the six domains. The purpose is to assign oversight responsibilities to individuals and teams that have the primary stake in that domain. Usually, no single person has authority over a specific domain, so the decision structure typically manifests as a network of committees, subcommittees, and working groups. The trick is figuring out the right mix of stakeholders to serve on the committees in a way that creates oversight but also respects your organization’s decision-making style and culture.

In the framework, we’ve identified a selection of governance roles and committees that organizations routinely implement. It’s not an exhaustive list or the only way to structure your governance model by any means, but it serves as a common starting point. In practice, you’d assign individuals to roles and create groups that align with your situation. But in all cases, your job is to identify the critical roles; outline the responsibilities and key decision rights for each role; arrange roles into groups; define a group-level mandate; and articulate the relationships and interdependencies among the groups.

Controls

Decisions made by stakeholders are typically compiled into documents that formalize governance decisions into standard practice. This includes policies, procedures, strategic plans, standards, and operating guidelines. These controlling artifacts enshrine key decisions into an agreed-upon set of rules and regulations that govern day-to-day operations as well as plans. The intention is to encourage behavior among people and systems involved in your geospatial program that aligns with your program’s objectives.

Examples of controls for the strategy and investment domains include strategic plans, governance charters, and project prioritization frameworks. On the technology and data side, there are reference technology architectures, data usage policies, and cartographic standards. Possible governance controls for the workforce and services domains include a geospatial skills matrix, mentorship guidelines, service catalogs, and service-level agreements. Your governance controls form an operational bounding box within which your geospatial program functions.

Processes

Governance is an ongoing activity, so having clearly defined processes is essential to ensuring your program remains a going concern. For geospatial programs, we’re primarily concerned with domain-specific processes that maintain and enforce matters like system performance, spatial data integrity, and service quality, as well as processes that cut across multiple domains for things like change communication and issue escalation.

Typically, organizations initially focus on efforts that smooth out their decision-making process. This often involves processes for recommending and approving new solutions or technology investments. These kinds of processes help overcome issues related to funding decisions. Beyond this, many organizations focus on establishing methods for dealing with critical service disruptions. For example, a midsize city organization we worked with developed a process to provide manual backfill support when its mapping platform failed to meet uptime requirements. This is a nice example of a process that supports a control (uptime standard) implemented through the governance structure.

Keep in mind, a governance process is different from a functional workflow. A workflow simply illustrates steps to complete a task. For example, you might define a workflow for publishing a new production map to an external corporate site. If there are steps in the process that enforce rules defined via the governance controls, then this could be construed as an important governance process. But if it’s just about describing a series of steps to make it easier for people to complete a task, then I’d classify this as more of a functional workflow than a critical governance process.

Performance

The purpose of your governance model is to ensure your geospatial investment delivers business results. That means that users and stakeholders derive real value from the solutions and services offered through your program, and the constraints of risk and resource utilization are understood and well-managed. In short, governance is about performance. How will you know if your geospatial program is delivering acceptable performance? You need to measure it.

The key here is to select performance indicators that demonstrate that your governance controls are working. An example of a strategic performance measure could be the percentage of funded projects that are aligned with the geospatial program’s strategic objectives. Platform access measures might consist of the number of users accessing a particular solution or map service. A data stewardship measure could be the percentage of data assets with an identified owner. The point is, the metrics you select indicate your geospatial program’s performance against a specified standard.

I’d also include systems you use to track and monitor performance measures as part of this governance component. The City of Calgary, for example, developed a dashboard to monitor system health of the city’s geospatial environment. The dashboard tracks metrics like service availability and database access requests and serves as an excellent governance tool for tracking platform technical performance. You can create dashboards such as this to track any performance measure, whether technical or nontechnical.

Using the Governance Framework

To use the framework, don’t attempt to tackle every item in the list. Instead, use it as a simple scorecard to help you prioritize your program’s most important governance items; consider the maturity of each item; and develop a plan to address the gaps.

Prioritize

Look at the six governance domains and decide which of these areas are a priority for you. Usually, these are the areas of greatest concern or areas in which you have a significant, potentially disruptive issue. Narrow the list down to the top one or two domains that will serve as a starting point.

From my experience, most organizations start by focusing on data governance. Many focus particularly on establishing controls concerning data usage and quality. Other organizations sprinkle in some aspects of strategy and investment governance, such as establishing a strategic plan and formalizing funding guidelines.

Once you’ve sorted out your focus areas, run through the four governance component categories (i.e., Structure, Controls, Processes, and Performance) and flag the components you currently have in place and the components you’re missing that you feel are acutely needed. This will tease out the critical pieces of the framework that will be the basis of your initial governance model.

Evaluate

The next step is to consider the relative maturity of each priority governance component. You don’t need to develop a rigorous maturity scale to do this. All you’re doing is identifying areas of strength and weakness. Table 2 shows an example of a scorecard that rates maturity using red, yellow, and green dots. The areas with red dots are key. These are components with a low level of control that may lack set decision rights and may have ad hoc processes and limited performance measures. Addressing these gaps is the highest priority.

Plan

Once you’ve completed the evaluation, you build out your action plan. Usually, this is done by packaging similar governance components into projects that you execute sequentially. Most organizations start with structural components first. There’s often a significant amount of interdependency between the roles and committees involved in your decision structure, so a single project to establish an overall working structure is a prudent starting point.

After that, focus on higher risk controls or processes. This could include the development of data security or privacy policies or escalation processes for resolving disputes over data or application access. Finally, develop performance metrics and implement performance monitoring systems to instantiate measurable management within your governance model.

Governance is a complex and multilayered topic. It is too broad to be covered by a single article. However, the intention of this distilled Geospatial Governance Framework is to provide you with a starting point for establishing key components of your geospatial program’s governance model. Work through the framework systematically, and don’t be afraid to augment the framework by adding your own controls or processes.

The author thanks Allen Williams, senior management consultant at Esri Canada, for his valuable contributions to the governance framework.

Resources

“Implementing governance for GIS (Part 1): Design Approach”

“Implementing governance for GIS (Part 2): Structure and processes”

“7 practical steps for improving your organization’s spatial data governance”