Firefighters are starting to see urban neighborhoods as overgrown forests. If homes are close together, made of wood, and surrounded by mature vegetation, there’s a need for mitigation work. Homeowners are creating defensible space—a buffer that acts as a barrier to slow the progress of fire. Both efforts are guided by maps made with GIS.

GIS-powered maps help fire departments model risks to create wildfire protection plans, inspect homes, and pinpoint places to reduce vulnerability. The same type of map encourages homeowners to trim trees, remove wood chips, or add screens on chimneys and vents to halt embers from entering. In this way, firefighters and community members come together to harden assets and protect property from worsening conditions.

The growing number of urban conflagrations has also brought emergency managers, firefighters, and wildland firefighters closer together. They have a history of collaboration, but with the escalation in fire-related tragedies there’s a need for more coordination.

Growing Pressure

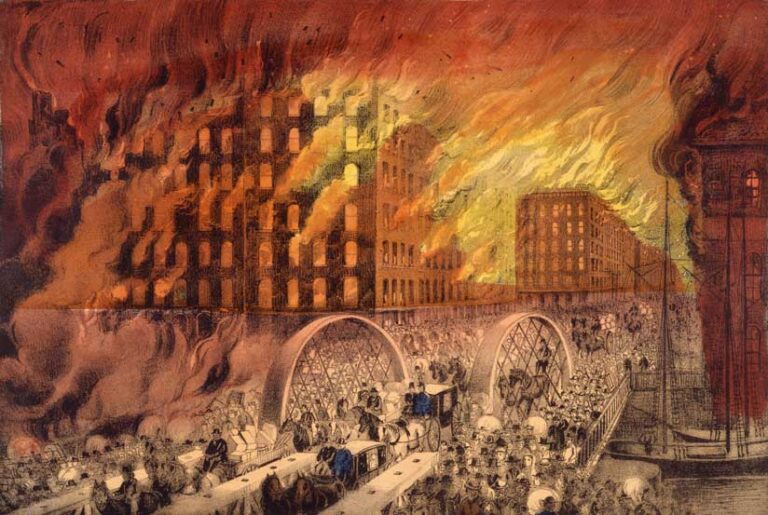

Fast-moving fires, which were once considered unusual, have swept through a growing number of communities. These urban fires include the Santa Rosa and Paradise fires in Northern California; the Marshall Fire in Colorado; the Lytton in British Columbia; and in 2023, the Lahaina wildfires in Hawaii, which were the deadliest in more than a century.

Yet, tragic fires hold lessons. Catastrophic great fires, such as the Chicago fire of 1871 and the fire that followed the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, led to changes in building codes and firefighting methods.

Now, the distressing growth in urban conflagrations is calling for further reforms. Structures at the wildland-urban interface (WUI), the transition zone between wilderness and developed land, are at the greatest risk. Due to higher rates of property damage in these areas, homeowners must shoulder additional financial burdens and have a more difficult time obtaining insurance. Given warmer weather and more extreme weather events, devastating fires are more likely to occur. These are conditions that cannot be ignored in the hopes that things will get better.

Data-Driven Assessments

Places known to be vulnerable to wildfire have started to get more serious. Many leaders have proactively applied GIS technology for a holistic approach to climate resilience. They make community-wide plans to drive on-the-ground actions. They look to forecasts to mitigate future hazards. They conduct traffic studies to improve evacuation routes and inform roadway reengineering.

A recent report, ON FIRE: The Report of the Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission, recognized that “mapping and analytical tools, which enable the geospatial identification of wildfire hazard or risk, are foundations for locally relevant, well-informed decision-making.” The commission recommended measures to better coordinate, integrate, and strategically align fire-related science, data, and technology. The report also suggested new performance standards for wildfire response. It cited the need for wildland fire efforts to align closer to emergency management and called for better federal coordination and support for local communities.

The federal government has provided preparedness funds furnished by initiatives such as the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Strong Cities, Strong Communities program and the US Forest Service’s Community Wildfire Defense Grants. A report from The Brookings Institute suggested that federal funds should do more to enhance local capacity.

More Integration and Coordination

With increasing pressures from climate hazards, all communities must prepare, and many require technical assistance. Wildfires are now threatening new areas and striking in all seasons. No community can afford to be complacent.

Major cities are using modern management information systems such as GIS to prepare and plan, coordinate actions, check the progress on efforts, and communicate conditions. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has mandated that states address social vulnerability alongside climate predictions. GIS solutions help even the smallest communities prioritize efforts.

Continuing innovations in remote sensing, modeling, and real-time decision support promise to enhance awareness of incidents and speed response. As in planning, modern tools enable more open sharing of data and coordination across jurisdictions.

The progress is in line with the need for more effective use and adoption of science, data, and technology for wildfire mitigation and management noted in a recent Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission report. The report recognized that “much of the science and technology needed to help mitigate, manage, and recover from wildfire likely already exists.” What’s important now is stronger coordination and alignment between the cadres of fire and emergency management professionals and within and among communities.