Between March and April 2019, two back-to-back cyclones battered Mozambique, destroying more than 800,000 hectares of farmland during harvest season. Cyclone Idai displaced hundreds of thousands of people in Mozambique. Six weeks later, Cyclone Kenneth brought powerful winds and heavy rains to the same, devastated area.

Cyclone Idai was an unusual storm that parked over land, dumped rain for days, and flooded an area spanning thousands of square kilometers. That period was also the first time in recorded history that two strong tropical cyclones hit the same country in the same season.

The cyclones devastated crops and livelihoods and left nearly two million people facing acute food insecurity. The United Nations (UN) World Food Programme (WFP) responded quickly, with two helicopters to ferry supplies and rescue stranded people. Given flooded roads, air support was crucial but not nearly sufficient to distribute food and find stranded people across such a wide area.

Using Drones in Mozambique

The world’s largest humanitarian organization, WFP delivers food assistance in emergencies and works with communities to improve food security and nutrition. WFP is usually among the first organizations on the scene during disasters because it has offices in more than 120 countries and leads clusters of UN emergency telecommunications and logistics staff who need to go in and set up before other teams arrive.

The response to Cyclone Idai was the first time WFP used a coordinated fleet of drones for disaster response. The timing for this effort was right because WFP had been conducting drone training with Mozambique’s National Institute for Disaster Management and Risk Reduction (INGD) to build in-country drone pilot capacity.

“Before, only the people with access to a helicopter could see the damage and do assessments,” said Patrick McKay, drone data operations manager for WFP. “But now with drone pilots mapping in really high detail, down to two-centimeter resolution, we could share that information with everyone, and even do remote inspections.”

“Each time the pilots came back, they told us the flooded area had gotten bigger,” said McKay. “They’d go by a stadium, and people were climbing higher and higher in the stands every time they flew past. When your primary tool for flying over large bodies of water is a helicopter that costs $2,800 an hour, you need to find a better way.”

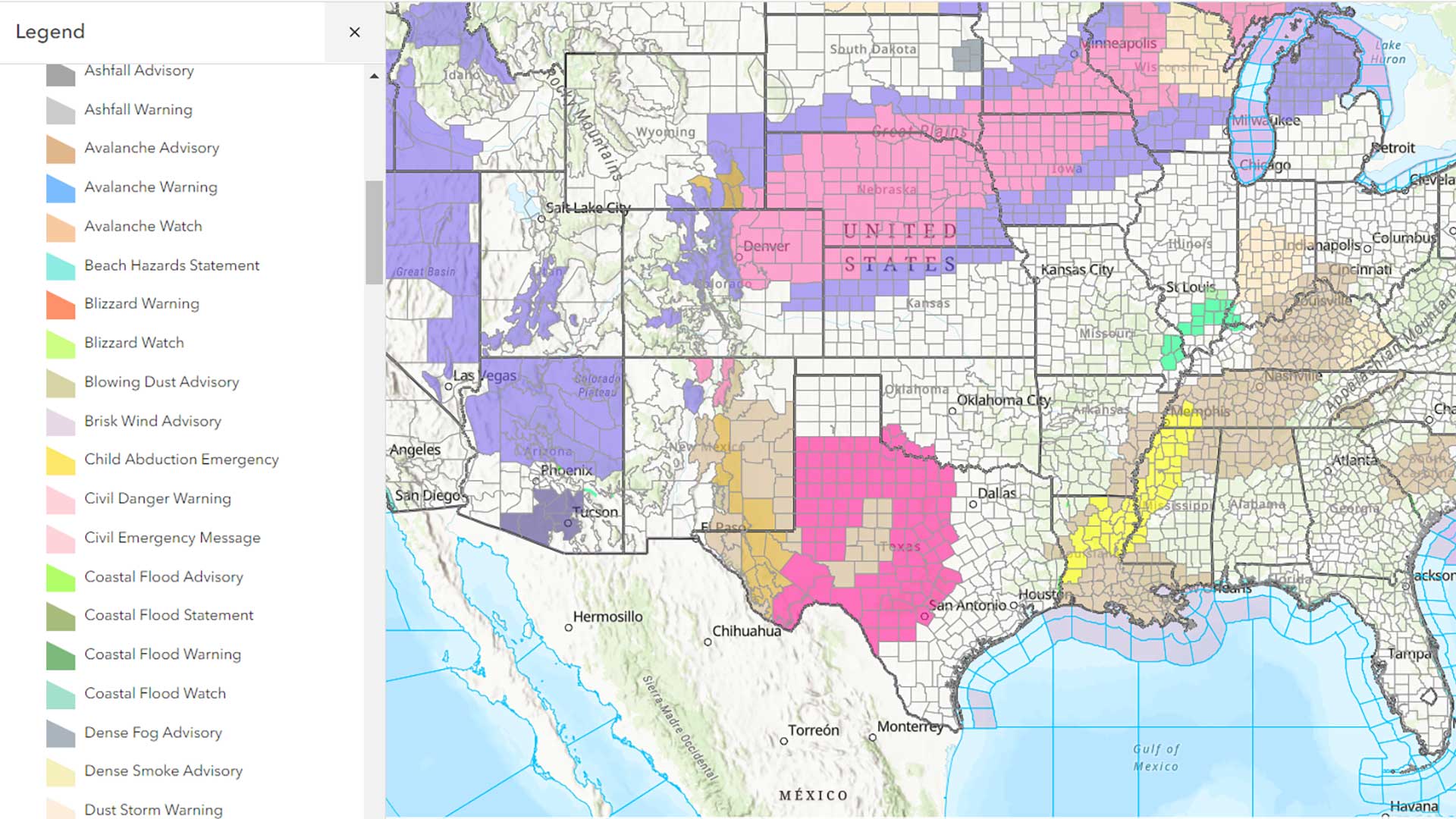

The drone pilots mapped the damage from flooding caused by Cyclone Idai and searched for survivors. This freed helicopter pilots to conduct rescue and supply missions. The images and videos the drones collected fueled updates to maps created with GIS that let all responders see what was going on.

Drones are now standard for every WFP emergency response, used early and often to find out how many buildings have been damaged and how far floodwaters reach, scout for survivors, and map changing conditions.

WFP’s use of drones has helped UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) inspect schools, assist the World Health Organization (WHO) assess the status of clinics, and support other UN organizations and in-country first responders rapidly understand conditions on the ground. GIS brings together drone-collected data—with details about people and structures—in purpose-built maps and apps to meet each organization’s mission.

Automating the Search for People Trapped by Floodwaters

Each drone flight can collect a vast number of images—from hundreds to thousands—that needed to be processed and reviewed.

“The faster we can go through them, the faster we can get to the people that need our help,” said McKay.

The cyclones in Mozambique in 2019 marked the first time WFP used a model with AI machine learning algorithms to automatically find and classify damage to buildings, which removed the need for people to look at every image. Using traditional AI methods, it might take a team of 20 people more than six weeks to label the data and train the AI model before it can produce accurate results. This was not a workable solution given the time-critical nature of search and rescue in Mozambique.

WFP turned to Synthetaic, an Esri partner, to solve the more challenging problem of quickly finding stranded people surrounded by floodwaters using imagery. Synthetaic divides imagery into tiles and employs a product that doesn’t require a pretrained AI model.

“That’s where our product RAIC [Rapid Automatic Image Categorization] comes in,” said Corey Jaskolski, president and founder of Synthetaic. “We can take completely unlabeled data, we don’t need any humans to label it, and we can search for things in the dataset by a single example query.”

With Synthetaic’s workflow, WFP was able to achieve results that were useful in finding people in floodwaters in a few days. Aided by AI in this way, responders could quickly send a boat or helicopter if the algorithm found a person in a tree surrounded by floodwaters.

Mapping Efforts to Prepare and Respond

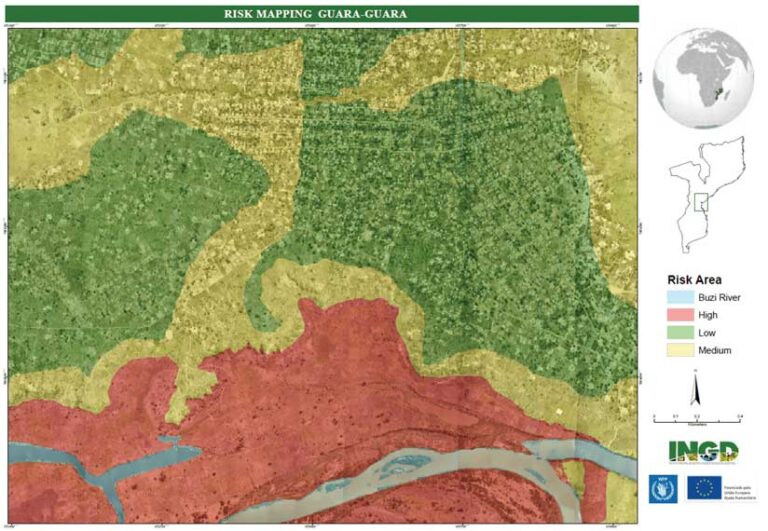

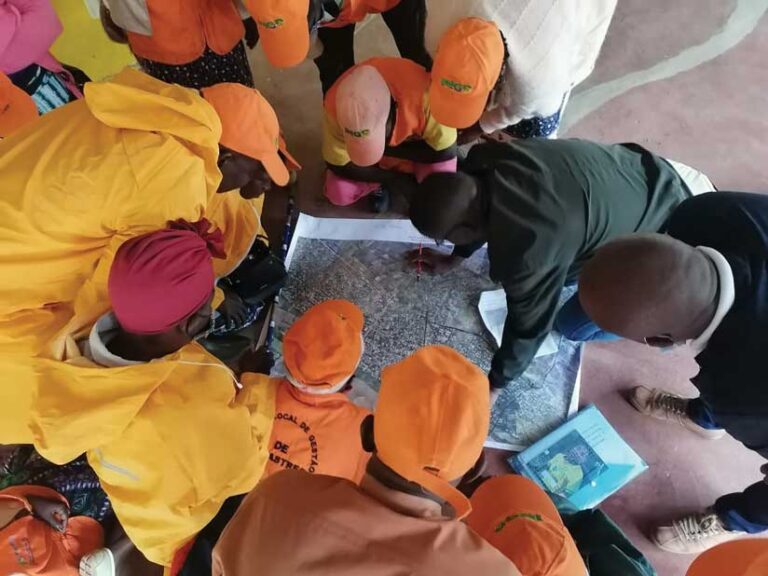

In responding to Cyclone Idai, WFP worked directly with Antonio Jose Beleza, deputy director of National Emergency Operations Center (CENOE) at INGD. Eight of the drone pilots came from the Mozambique government. With their local knowledge, they began mapping where they thought people still might be.

Every day, drone teams would meet in the morning, disperse, and meet in the evening to coordinate activities and process images to update maps. Evening meetings were for coordinating the next day’s flights and the areas to cover. In the morning, the teams would assign people to ground vehicles, helicopters, and boats to reach flooded areas. The drone teams would check on villages, determine if they were flooded or clear, and document any people walking through floodwaters toward safety.

Flooding in Mozambique had started even earlier, with Tropical Depression Desmond, which dropped more than 400 millimeters (15¾ inches) of precipitation in less than 48 hours in Beira, the country’s second-largest city, in January 2019.

The entire city was flooded, which led Beleza to try drones to assess the damage. “At that time, it was just me and my colleague Agnaldo Bila with two drones,” he said. “We couldn’t map very large areas, but we were able to cover critical areas and share the footage in real time. The images we collected on the ground were integrated in real time and for the very first time into the European Union’s Copernicus Emergency Mapping Service, which was activated at the request of WFP to conduct rapid assessment of flooded areas.”

The map helped establish accommodation centers in places that weren’t flooded and showed others in the government the value of drones and mapping.

“Initially, we were focused on disaster response, but we wanted to be proactive,” Beleza said. “Disasters will occur, and we want to be more prepared. We don’t want extreme events to turn into disasters anymore.”

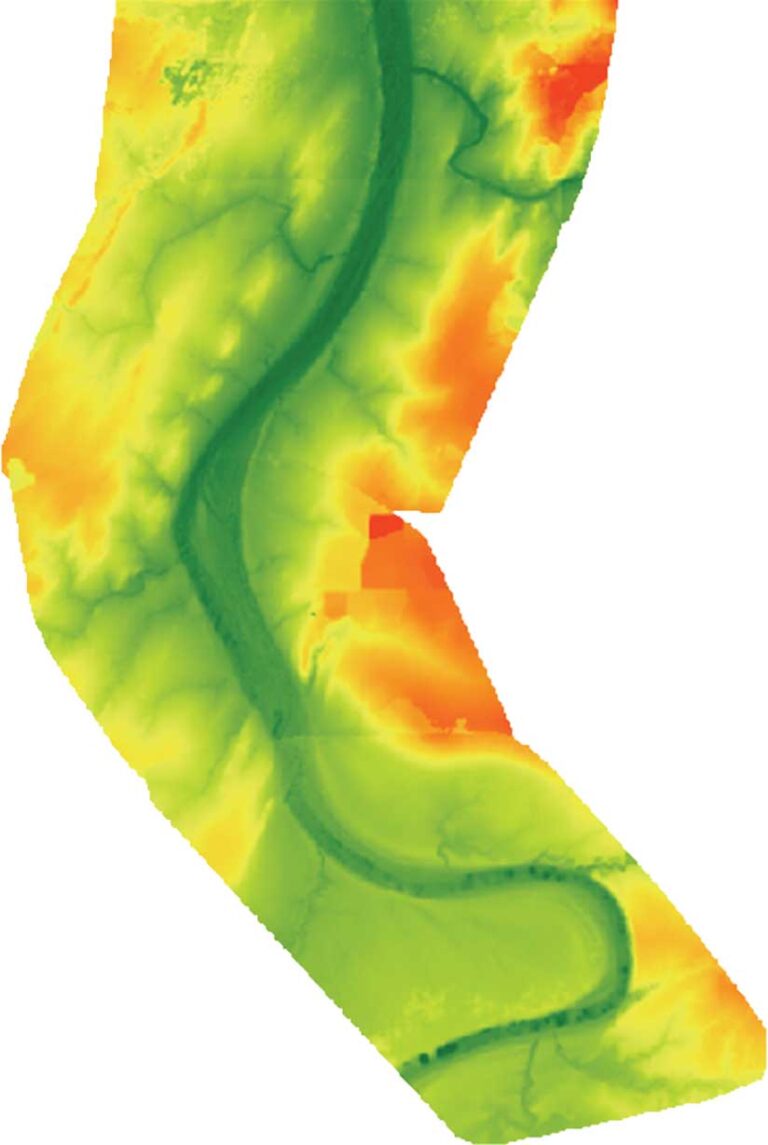

Beleza and his team have been working with the Italian Centro Internazionale in Monitoraggio Ambientale (CIMA Foundation) on hazard mapping. The CIMA Foundation has created a hydrological model for the Buzi River watershed using satellite imagery, and recently drones were flown to improve the accuracy of the model.

“We flew the drones over 850 square kilometers of the Buzi River, then we processed the data and created a very high-resolution digital terrain model [DTM],” Beleza said. “When the rainy season comes, local governments can simulate floods and determine when and where the water will arrive downstream. We’re sure that this will trigger community early actions and save lives.”

GIS is used to look at different layers of data to model different flooding scenarios, design evacuation routes, and identify the safest places for accommodation centers.

“We combine science, technology, and local knowledge to prepare the communities and local governments in a participatory manner,” Beleza said. “Every year we are seeing more frequent flooding. That has motivated us to go there and do something for these people.”

WFP is greatly encouraged with how people in Mozambique continue to grow their skills. Mozambique now runs its own drone response team and uses drone imagery-derived maps to predict risks and hazards.

“They’ve got the expertise and drone equipment, so when the storms hit this year, they didn’t call us because they knew exactly what needed to be done,” McKay said.

For Beleza’s team in Mozambique, the drones and AI analysis have been a game changer.

“We’ve been saving lives,” Beleza said. “We are taking the opportunity to learn from the drone deployments we have made so far to improve the way we deal with this technology when it comes to disaster preparedness and response.”

Learn more about how GIS helps organizations deliver effective humanitarian assistance.