An African charity, responding to widespread flooding in Mozambique in 2013, has developed a faster and more accurate way to pinpoint where relief is needed that uses Collector for ArcGIS and its offline capabilities.

Torrential rains caused the waters of the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers to burst their banks, decimating nearby farmland, destroying bridges and roads, and affecting more than 200,000 people. Humanitarian agencies responded by providing rescue, food relief, and shelter. Many of the region’s roads and bridges washed away, so ground-based response was often not an option. Relief needed to come from above, but with airstrips flooded, that meant helicopters. Wings Like Eagles (WLE) was one of only two helicopter relief organizations based in southeast Africa that responded to the disaster.

Much of the population of southeast Africa is scattered across rural areas. Although mobile voice connectivity is available in these areas and much used, there is little or no mobile data connectivity. WLE’s team used portable GPS and air maps marked with grease pencil hurriedly written in flight. These notes were then manually transcribed to notebooks and paper maps on the ground for use by the emergency planning authorities and other aid and rescue pilots.

“The large scale of the disaster made it increasingly clear to us that our survey methods are too slow relative to the criticality of these situations,” said pilot Clive Langmead, flight operations coordinator for WLE.

To speed up and improve its surveys, Langmead asked Esri partner Helyx, a GIS firm based in the United Kingdom, to make a data collection app for aerial surveys that could be used offline with a mobile device such as an iPad, iPad mini, or smartphone with a large screen. Data collected would be synced when a helicopter returned to base.

Anneley McMillan, GIS consultant for Helyx, knew the new beta version of Collector for ArcGIS had offline capability and was available for field testing. “I immediately thought of Esri’s data collection app when Clive came to us,” said McMillan. “Not only did it have the disconnected editing feature, but it was also preconfigured, which would save all of us money and time.”

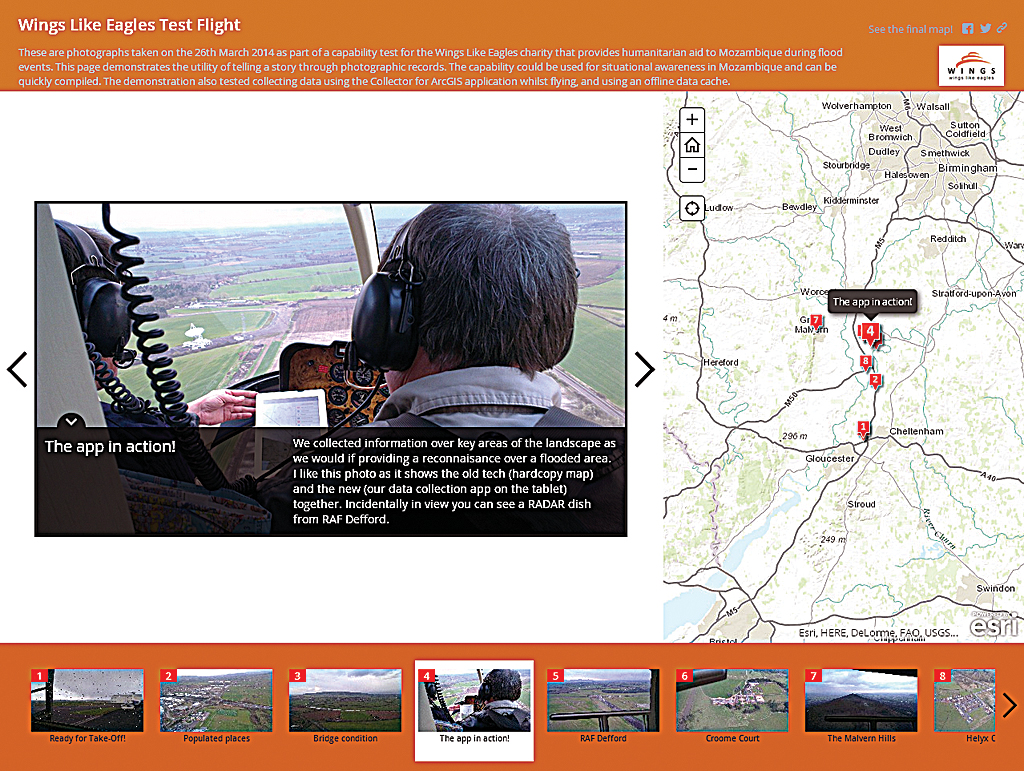

To test the disconnected editing mode in Collector for ArcGIS, Langmead and McMillan set their tablets to airplane mode and took to the skies over South Worcestershire, England, inputting data into the app as they flew over the region. They identified locations, such as hills where people would take shelter from a deluge, that would be classified as incidents in a flooded rural area.

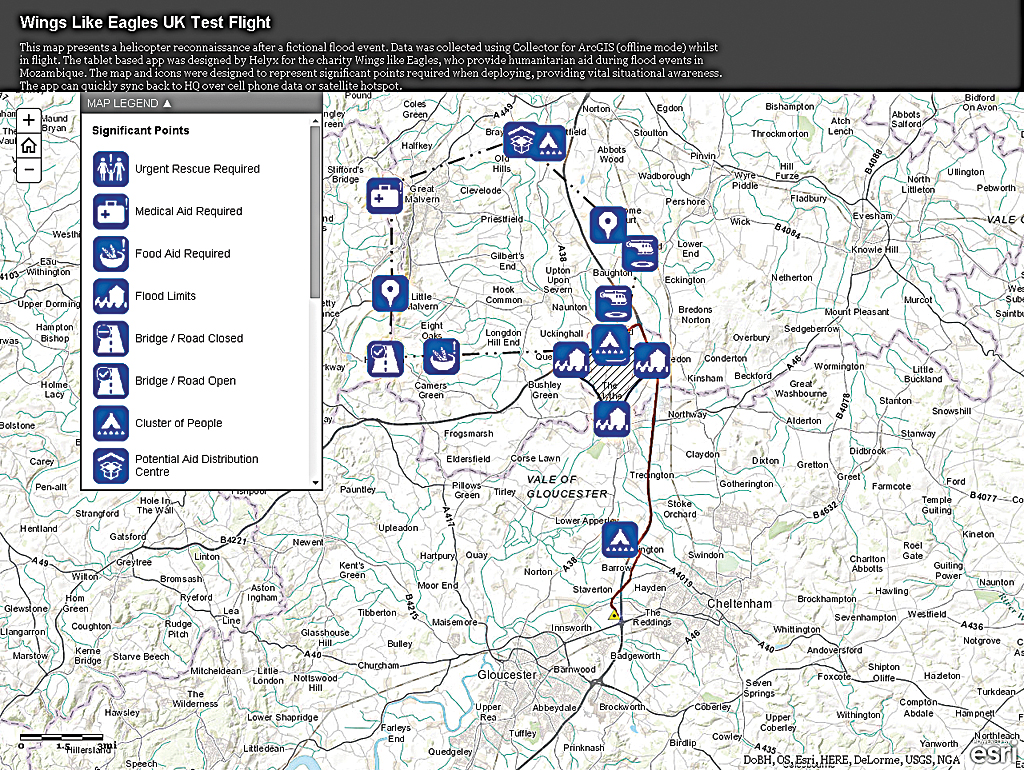

When they landed, Langmead and McMillan easily synchronized map edits made in flight. Even with the hiccups that typically accompany beta software tests, they noted the digital process was much quicker and more consistent than the handwritten survey. It allowed data collection without cell phone data coverage or Wi-Fi signal and could use a satellite hot spot to synchronize data back to base. The finalized data was presented in an embeddable web map with symbology denoting locations where urgent rescue and medical aid would be needed, flood limits, and bridge condition status. A stand-alone Esri Story Map app detailed the test flight and displayed pictures from the sortie.

Over the course of a year, Helyx tailored the app specifically to Langmead’s requirements. For instance, the app was configured to use the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) symbology set. This set of 500 free icons relating to humanitarian assistance were designed to be understood by relief workers regardless of language.

“There is huge potential for the online web maps to be further developed,” said McMillan. “For instance, it is a great post-deployment tool to debrief and learn lessons. Using the time element, in particular, allows dissection of postdisaster response in slow time after the event. It can also be used to assess vulnerability and build resilience. If there are common areas that require assistance every time there is a flood, these can be flagged as high-risk areas, and strategies can be developed to mitigate the risk.”

With the application now tested, the WLE has a quick response data strategy for targeting relief delivery. In the future, if flooding in Mozambique makes most bridges and roads inaccessible, WLE will be able to fly over farmland, assess damages, and record the locations where relief is needed. This data can be synced back to headquarters and provide a rapidly updated picture of the situation for the Mozambican disaster response authority and other responding agencies such as the UN and Red Cross/Red Crescent.

“Quick surveys are key to getting emergency aid to the right people,” said Langmead. “A precise overview of a region’s flooded schools or clinics immediately shows the scale of the problem to government and UN aid partners. And, of course, speed and location are essential for flood rescue.”

Collector for ArcGIS allows data to be collected relating to medical aid and food aid requirements, emergency rescue, potential landing sites, and potential aid distribution points. The application could also be used in streaming mode to map flooded areas without manual digitization by the crew.

“This is an amazing leap forward from the way we did surveys before,” said Langmead. “All that scrabbling around with notebooks and paper in the aircraft just disappears.”