More than a quarter of the world’s population—more than two billion people according to the United Nations (UN)—lack access to safe drinking water. And nearly all of them have no way of knowing if the life-sustaining liquid they draw from a village pump could make them deathly ill or even kill them until it’s too late.

But an enterprising group of young computer coders in India created Saaf water, a low-cost system that can go a long way to ensure that water—one of the most basic human needs—will not harm those who do not live near modern plumbing or have access to purification methods.

The group—Hrishikesh Bhandari, Jay Aherkar, Satyam Prakash, Manikanta Chavvakula, and Sanket Marathe—built a water quality sensor and analytics platform that is accessible to people living in rural areas. Low-power, cellular-enabled hardware monitors water quality parameters. The data collected is stored and disseminated using the IBM Cloud. The system uses artificial intelligence (AI) to predict circumstances that will degrade water quality so that it can alert people to the likelihood of contamination of the water they depend on for drinking, cooking, and cleaning.

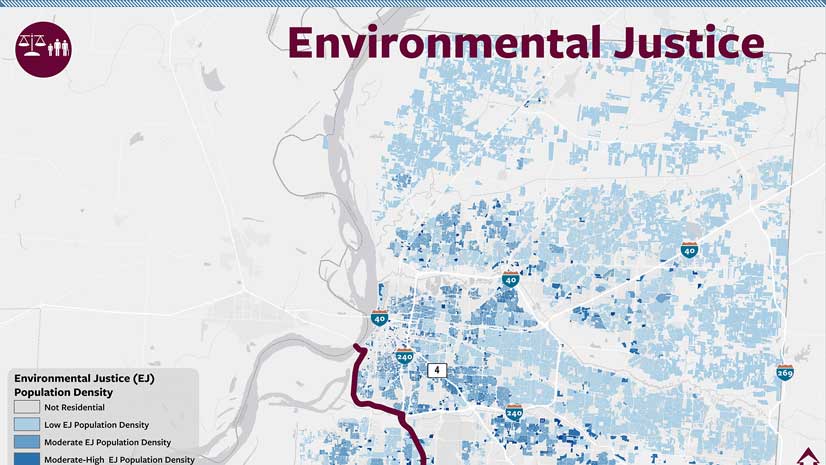

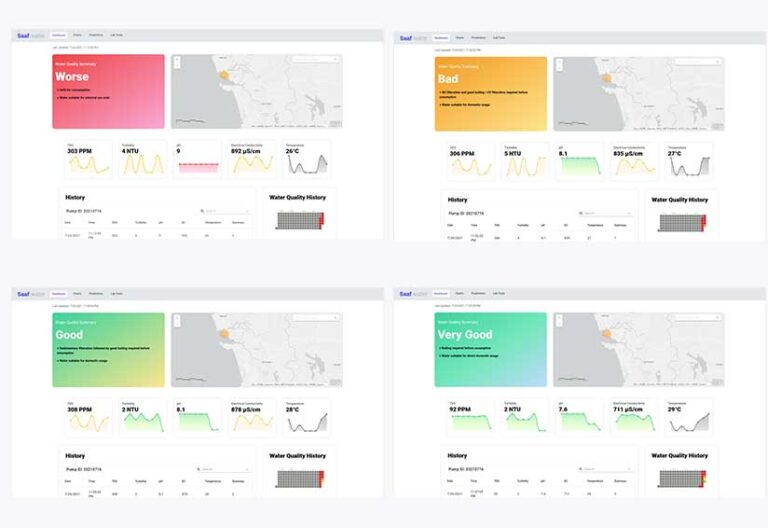

Contamination spots and areas likely to become health risks are plotted on maps using GIS. The GIS dashboard, along with the color-coded and regularly updated smart maps, can keep residents aware of the quality of their drinking water in real time as well as make the data readily accessible and understandable to government entities.

Saaf water was chosen as the grand prize winner of IBM’s 2021 Call for Code Global Challenge contest from a field of 500,000 developers who came from 180 nations. This first-place finish comes with a $200,000 prize and the promise of expertise to guide the group and help take the idea from proven prototype to widespread deployment as a working solution. According to Indiatimes, a mainstream news source in India, “The low-cost device could help save millions of lives in India if deployed on the large scale.”

A Mother’s Illness Spurred Innovation

Bhandari’s mother had become severely ill from contaminated water. It took three painful months for her to recover. This event set in motion a journey of discovery that may ultimately save many thousands of lives and relieve suffering.

Although parts of India are very modern, many areas still suffer from a lack of drinkable water and the treatment services to make water safe. The issue of contaminated water is complicated by the fact that areas without modern plumbing and treated water also have poorly managed garbage and human waste disposal systems. In fact, the UN report notes that 3.1 billion people—or 46 percent of the world’s population—fall into this category.

After thinking about his mother’s illness, Bhandari checked with his friends to see if anyone close to them also had suffered after ingesting tainted water from their village or neighborhood’s traditional source. He found water-related illness to be common. Everyone seemed to have a relative or friend who was sickened at some point by contaminated water. As Aherkar, Prakash, Chavvakula, and Marathe did their research, they, too, were galvanized into action by what they found.

Bhandari said, “That’s why we thought, ‘Let’s build a solution around this,’ because it’s not a problem that just we’ve encountered, but it is a problem that everybody is going to encounter in the future or is encountering currently.”

Saaf water Was Born

As group members began to organize their thoughts and set up a plan to do something about the ongoing problem, they formed Saaf water. In Hindi, saaf means clean.

They decided that there had to be a way to help the situation. It might be an app or a device that could save lives, wouldn’t cost a lot, and would be easy for the average person to understand and use. They realized that to be effective, the device and the system would have to be simple to operate and understand and low cost so it would be within the reach of low-income communities.

The system uses simple hardware sensors that indicate the condition of the water source—green for safe water, yellow for water that has a high likelihood of being unsafe, and red to warn of confirmed contamination. Sensor information and layers of data gathered from weather patterns, seasonal correlation, population growth, local farming methods, and commercial development are used to assess trends affecting groundwater quality.

The goal of Saaf water is to put the hardware-software system in the communities that need it as soon as feasibly possible. That’s why the team members, who were both excited and humbled by their win, are also anxious to deploy the solution and make good on their pledge to improve conditions for more than two billion people.

“My family felt proud,” Marathe said. “For me, it’s not about celebrating the win; it’s about getting a long-term responsibility to apply things and to take things forward.”

Climate Change Complicates the Solution

It’s not just a lack of proper human waste disposal or industrial runoff that causes biological and chemical contamination. Climate change adds another layer of complexity.

“Because climate change is on the rise, what is happening is sea level is rising and penetrating into groundwater. This pattern increases salinity and bacterial contamination,” Bhandari said.

After winning the IBM global challenge, the five members of the group have continued to refine their system. They are trying to collect additional data, including data on historic weather patterns and current water quality. This data will help refine the algorithms that predict when contamination is likely to increase. Warnings can be sent out to those areas and local governments can be alerted to begin more thorough water testing.

Visualizing the Analysis through Mapping

To make the information accessible to as many people as possible, the group recognized the power of plotting data on maps.

“With maps, what happens is we can create a spatial awareness system,” Bhandari said. “Users will get a sense of depth. They’ll get a sense of how water quality spreads across the landscape.”

That helps governments see the larger picture and trends in contamination. It also can help neighborhoods, communities, and even regions develop a bond over water needs that could translate into the political will needed to solve the problem.

In addition to IBM resources, the group had assistance in creating maps that allow users to visualize trends and problems. “With Esri India’s help recently, we have brought spatial awareness to a new level, which provides our users a sense of what’s happening in their neighborhood,” Bhandari said.

The Saaf water system also has the capacity to suggest treatment and prevention options based on what the electronic sensors detect in the water.

Bhandari’s mother went through a terrible three months and seemed proud that her son’s project may save others from illness and death.

“I didn’t see her reaction in person,” Bhandari said. “But from what I heard from her and my brother, she was literally crying when she heard that Saaf water had won [the IBM global challenge].”

Through simple water-testing devices, cloud-based data storage, machine learning, and GIS visualization, the Saaf water group has created a way to alert people in neighborhoods and villages that the water they depend on may sicken them.

Learn more about how GIS is used to manage water quality.