From her couch in Ohio, Katherine Wright (who goes by Kelly) created a web GIS app as part of a class that she hopes will help curtail tungiasis, an epidermal parasitic skin disease that is widespread throughout sub-Saharan Africa and South America.

Initially, Wright didn’t know anything about this neglected tropical disease. Her friend’s boyfriend had some itchy bumps that she thought looked like chiggers, the juvenile mites that cause temporary discomfort to their short-term hosts. When she gave him her diagnosis, he exclaimed that he did not have jiggers—using a “j” to begin the word. Wright looked up jiggers and found out that they were not the same as chiggers, but rather were equivalent to chigoe fleas.

These parasites can permanently disfigure and cause physical disabilities to their hosts, though they are not normally fatal. There is no concrete data on how many people have tungiasis. While it may be endemic in almost 90 countries worldwide, the disease could be at epidemic levels in many sub-Saharan African countries.

An infestation occurs when female chigoe fleas burrow just underneath the surface of a host’s skin. Animals as well as humans can be infested. Humans likely contract the fleas when they walk barefoot or without sufficient footwear on warm, dry soil and sand. Tungiasis, which disproportionately affects the world’s most impoverished people, has flourished over the last 50 years because of growing rural populations and increasing construction of dirt roads in those areas.

“I started thinking, why isn’t anyone doing anything about this, and why hasn’t anyone applied GIS to this?” Wright recalled. She knew the Carter Center has almost eradicated Guinea worm disease, a parasitic infection that affected 3.5 million people in 1986 but in 2015 only infected an estimated 22 people. “They were using GIS in order to target areas that they knew would be having this problem,” Wright said. She started thinking how she wanted to use GIS as a management strategy for the eradication of tungiasis.

A Meandering Road to GIS

Wright’s path to GIS has been long and winding. But when she finishes her master’s degree in geographic information science and technology (GIST) at the University of Southern California (USC) in December 2016, she knows that she will be able to make a difference.

“I really believe that GIS has the power to effect change,” she said. “I want to try and do that.”

And by all accounts, this young, enterprising woman will be able to do just that.

“She is absolutely among the very best students I’ve known in 20 years,” said Jordan Hastings, one of Wright’s professors at USC who is now a research associate at the University of California, Santa Barbara’s Center for Spatial Studies. “She is both engaged and engaging. She has a rare interest combination in…environmental topics, technical skills, and social commitments.”

Wright has always been interested in maps. She started out—as so many GIS professionals do—being the navigator on road trips when she was a kid. She decided to study molecular genetics in college at Ohio State University. She ended up transferring to the University of Texas (UT) at Austin because it had a large budget dedicated to biological sciences research.

While carrying a full course load, Wright also worked full time at Dell in tech support. Because Dell is located outside Austin’s city limits, Wright needed a class that didn’t require her to be at UT’s downtown Austin campus. The online course offerings were slim, so she decided to take a class in urban geography.

She quickly found the subject matter exciting. She got an A in the class. It was the best she’d done academically in a while.

“I was hooked,” she recalled. “Taking that class really made things click. I really got it, and I really understood the world I was seeing around me all the time.”

So Wright switched majors. She excelled at geography, though she felt that GIS was still pretty heavy on computer science at the time, so she didn’t think it could be her focus. Wright graduated with distinction from UT with a bachelor’s degree in geography, specializing in urban and regional planning and natural resources.

From there, she bounced around the United States and tried a slew of different jobs. She worked with a butcher for a little while, then headed to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina to help with the rebuilding effort.

After that, Wright moved to the Florida Keys, where she spent two years as an interpretive park ranger at Long Key State Park. She took visitors on guided walks and explained the flora and fauna, focusing on birds—her specialty—since the area is a major migratory path. She also documented all the native plants in the park, redesigned trail maps, and trained other rangers on how to do interpretive programming.

She moved back to Austin in 2008, where she became a park ranger at McKinney Falls State Park. But when the financial crisis hit, she lost her state-funded job. So Wright headed back to Ohio, where she was from originally, and did a stint with the Columbus Zoo before getting a job at Time Warner Cable in tech support and data analysis. While there, she monitored the health of the network’s lines and data for more than 2 million people.

When her grandmother needed care, Wright took time to do that. Her grandmother said she’d be happy to help Wright out with graduate school. Shortly thereafter, Wright was on LinkedIn when she saw a targeted advertisement for USC’s GIST online master’s program. She signed up to learn more about it and just two weeks later she was in class.

Around the same time, Wright began an internship with the Ohio Department of Transportation (DOT). She started in the aggregate geology division, then moved to the technical services department. She currently holds an internship in the CADD and mapping department, where she’s working to increase interoperability between ArcGIS and MicroStation. Wright is also helping to archive historical aerial photos taken from the 1940s through today and make them available to the public through ArcGIS.

According to Mark McCloud, the CADD manager at the Ohio DOT, Wright is essentially leading the project to archive aerial imagery. “She’s really been kind of the key person to this project,” he said. “She’s already started building the Python scripts to geolocate our imagery.” This is quite a feat, considering Wright has only just started learning Python in her master’s program.

“Our office is kind of a learning point for her,” McCloud continued. “When she sees something and she knows she wants to learn something…she takes it and gets right on it.”

A Dataset to Battle Tungiasis

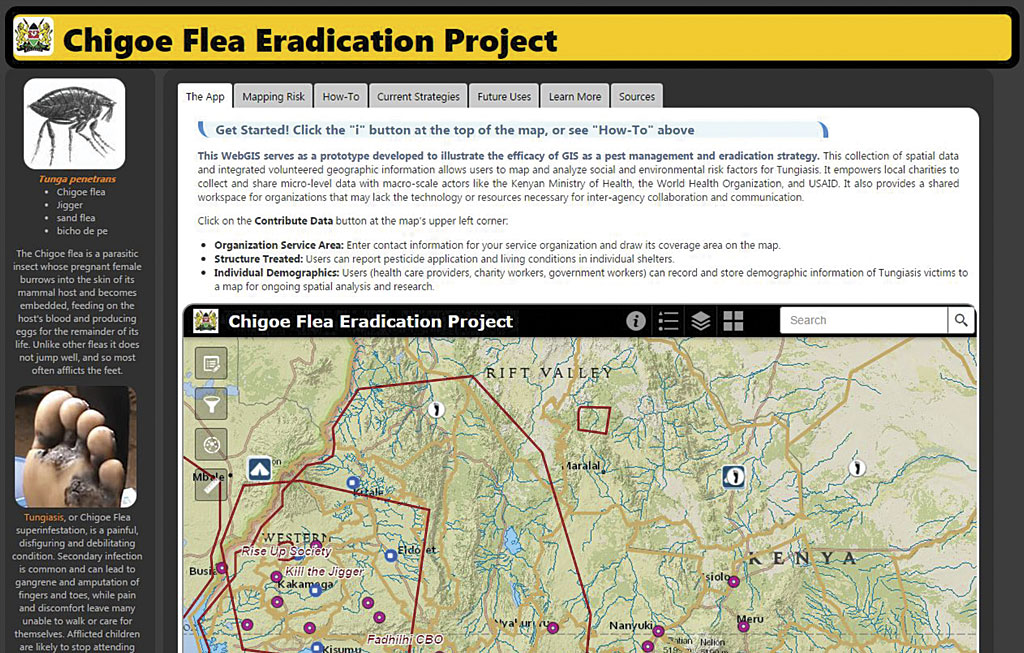

And that is exactly what Wright did when she started researching chigoe fleas. At the time, she was taking a web GIS class. As an assignment, she had to design and implement a distributed web mapping service for a specific purpose. She chose to focus her project on tungiasis in Kenya because Kenya is an English-speaking country that has available GIS data and reportedly has almost 50 charitable organizations working to combat the disease.

However, most of the research on tungiasis comes from Brazil. There was no data about chigoe fleas in Kenya. She wanted to get an idea of the distribution of the disease in the country and pinpoint some of its causes.

“My goal is to try to create a dataset that is functional,” said Wright. And she wants other people—especially charitable organizations—to be able to use her dataset to curb the disease.

For her project, Wright first created a prototype app that would allow citizens and aid workers to overlay different datasets to explore the underlying causes of tungiasis. She used open data from sources such as the International Livestock Research Institute, Open Data for Kenya, and Kenya Open Data. Because Kenya’s borders have changed dramatically over the last 30 years (at times, as many as 100 new administrative units were added in a year, Wright said), it was exceedingly difficult for her to find shapefiles with the correct administrative boundaries. But once she got them, she used USC’s organizational account to put all the data together in ArcGIS for Desktop and then upload it to ArcGIS Online. Wright then used Web AppBuilder for ArcGIS to create an app that allowed users to explore the data.

After the course was over, Wright spent her winter break developing three editable feature services for the app using ArcGIS for Server. The idea is to have users contribute information on the charities working in an area, identify the pesticides being used, and record the characteristics of the people who are being helped by aid workers. Drop-down menus would be used to retain standardized data. A charity, for example, could register its boundaries and list its contact information. Workers spraying pesticides or conducting indoor residual spraying (coating indoor surfaces with lingering insecticide) could report where they’re spraying, how long the treatment will last, and the condition of housing. Aid workers could capture the demographics of the people they assist. Wright is still figuring out how to deal with the privacy issues that go with health care and humanitarian work. Currently, users can input data, but the app is not displayed publicly.

“I’m in the process right now of contacting organizations to see if this is something they’d be interested in either adopting or trying out,” Wright said. She would also like to get some feedback from them to see how she can make this meet their needs.

A Way to Change the World

Wright has created a website with information about the chigoe flea in Kenya and an extensive help file on how to use her app. She plans to turn this into her master’s thesis project. She also thinks that other organizations—such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Carter Center, or the World Health Organization—could use the app to help eradicate the chigoe flea or other neglected tropical diseases. And, given her experience in the park service, she wonders if the app could be used to track and quash invasive species.

“Here in the United States, we have countless invasive species—whether they be plants, reptiles, fish, mammals, or even viruses,” Wright said. “For me, this is also an application that can be segued into invasive species control.”

She envisions having citizen scientists collect and record information on invasive species in their areas, since they often have better access to hard-to-reach places where they live than do scientists who parachute in and out of an area.

“We all have the power now to help these problems,” stressed Wright. “You can take disparate data—just numbers—and give them meaning by providing them with a spatial context. You turn data into information, and people get it when they see it that way.”

Because of advances in GIS technology, such as web GIS and app building tools, she truly believes that “normal people can take part in changing the world.” Wright is anything but “normal”—though she is certainly already taking part in changing the world.