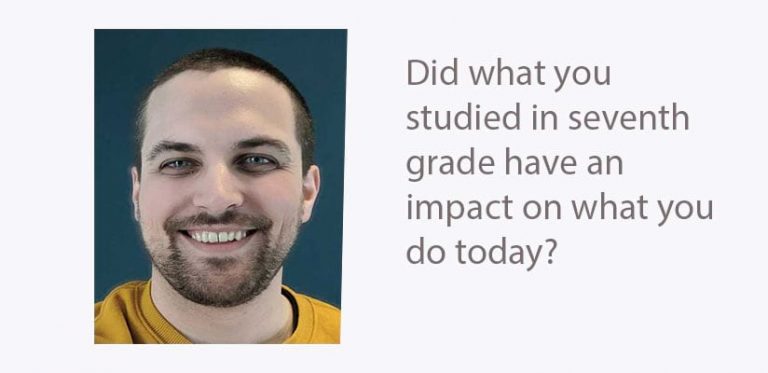

For Nate Ebel that question is a no-brainer. His first experience using GIS technology 18 years ago started him on a path that led to his current career as a software developer.

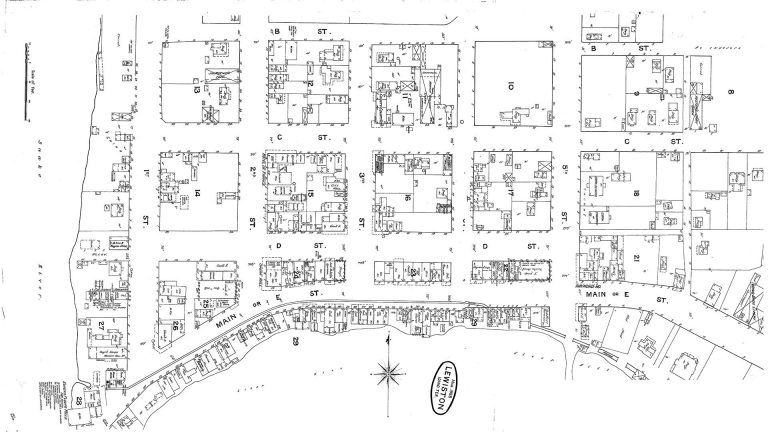

During the 2001 school year, Ebel was enrolled in a GIS class for gifted students at Jenifer Junior High School in Lewiston, Idaho, taught by Steven Branting. Students in the class used Esri technology to study Lewiston, including a project investigating the relocation of a cemetery in the city. They used GIS, GPS, and satellite imagery to study the sequence of reburials from an 1860s era cemetery to a cemetery that opened in about 1889.

The class won an Esri competition for schools to map and analyze their community, which earned Branting and two students a trip to San Diego, California, to speak to thousands of GIS professionals during the Esri User Conference Plenary Session. A 13-year-old Ebel, his classmate Ian Coleman, and their teacher Branting gave a presentation about the community atlas they created and the graveyard relocation project.

Branting’s class covered topics such as celestial navigation and position fixing, GPS fundamentals and applications, digital photography, introduction to image analysis, and data analysis, and visualization with Esri software.

His seventh-grade project opened Ebel up to a new world of location technology.

“We had a computer at home, but I had never used the computer for anything more than typing up a research report and playing some games,” Ebel said in a recent interview. This was my first exposure to doing cool things, including GIS, on the computer,” he said. “That sent me down the technologist path. I remember thinking I would be some kind of engineer but didn’t know what kind.”

Until his senior year of college, Ebel was planning on pursuing a career in GIS. “I figured I would probably be a GIS analyst, and honestly, I was already in that role at that time too,” he said. “In the summer, before my junior year of college, I got a job as a GIS intern with Lewiston Public Works,” he said.

The job went well, so Ebel worked there for four years part-time during the school year and full-time during the summers. Ebel attended the University of Idaho, majoring in geography with an emphasis in GIS.

He had tried but didn’t like a general computer science and programming class. Instead, Ebel enrolled in a GIS programming class and realized, “Here’s how we can write code to make these GIS projects at work easier to solve. Solving real-world problems clicked in a way the general computer science instruction didn’t. It was just like back in our original work with Steve [Branting].”

Those problem-solving skills helped him as a GIS technician for Lewiston. He was working on a project that involved multiple parcel datasets that needed to be validated, cleaned up, and combined into a single dataset. Using Python and the Python site package ArcPy, he automated the process. By letting the computer do the work, he saved a huge amount of time and money. Two weeks into the project, which was expected to take two full-time staff members six to nine months to complete, Ebel had pretty much finished it.

That’s when Ebel realized that was what he wanted to do, he wanted to be a software developer. “I was in school for two more years to get a master of science degree in computer science, and then got a software developer internship at Esri in 2013. I spent the summer at Esri, finished up one last year of school, and worked for Esri again for two years on the Android development team.”

Because he had started using GIS in seventh grade, when Ebel began work at Esri, he had already had 10 years of GIS experience. “That really gave me a leg up. I had domain knowledge and could contribute to discussions and decisions,” he said, adding that he worked on apps such as ArcGIS Explorer, ArcGIS Navigator, and ArcGIS Collector.

Ebel left Esri in 2016 to focus on education technology. For the last four years, he has developed consumer-facing apps for startups and has been active in developer communities, writing, and doing public speaking. He also has done some teaching. He recently taught an Android development course at a community college in the Seattle area.

“I’m an engineer first but went out of my way to host meetups and help people learn to write Android apps,” Ebel said. “I really enjoy meeting people, sharing information, and creating tutorials. Through all of this was the thread of GIS and computers.”

Ebel credits that first GIS class and the guidance Branting gave him for helping to think through problems to find solutions.

“Anyone can dabble with the GIS architecture,” Branting said when contacted at his home in Lewiston, Idaho. “As Alexander Pope wrote, ‘A little learning is a dangerous thing.’ Looking for mastery, my focus with him and his classmates was to help them internalize how to know—diversely and authoritatively—in a loop commonly called O-O-D-A, [which is] an acronym for observe, orient, decide, act. Pose a good question, invent chaos, and search for patterns and order.”

Ebel also said he is thankful for the public speaking and technical writing skills that he cultivated and honed during his junior and senior high school years.

“That seventh-grade class was not a GIS class per se, but something like, ‘Learn to solve problems.’ Steve got us to look at a problem from different perspectives. He trained us to look at things from all these different angles, to make inferences, and to use data. The whole first part of the course was training us to think about solving problems,” Ebel said.

“When I talk with people today, one piece of advice I give is that tools and frameworks are not as important as they seem. There’s all this attention to inputs and outputs, but I try to teach people that how you think about the problem is much more relevant and more challenging than being able to sit down and write the actual code. That’s what Steve [taught] us.”

For more information on using GIS to teach K–12 students, for free (even remotely), see Esri’s program for schools.