In 1984, Richard Resl was fresh out of high school and ready for an international adventure when he went to see a travel agent. Being from Austria, he wanted to go somewhere tropical, a place not gripped in cold weather and the Cold War. He wanted to experience a new culture and be in touch with nature. The travel agent told him about a cheap flight to Peru.

“What language do they speak there?” he asked.

“Spanish,” said the travel agent. “You will pick it up.”

And that is how Resl—a tall, lanky man with long blond hair and a passion for geography—began his journey to Latin America, where he eventually ended up in Ecuador, now running a nonprofit organization called AmazonGISnet. He teaches indigenous people from 11 nations how to use GIS and other geospatial technologies to protect their land and ways of life in the Amazonian rain forest.

Resl was at the 2016 Esri User Conference with indigenous leader Domingo Ankuash from the Shuar nation. Together, they accepted the Making a Difference Award from Esri for the work AmazonGISnet does to support participatory planning among the indigenous communities as they strive to preserve their culture, create sustainable economic development opportunities, and protect the fragile environment in the Amazonian lowlands of Ecuador.

That first trip to Peru (with additional stops in Bolivia, Argentina, and Brazil) set the stage for what Resl would do with the rest of his life and where he would do it.

“I fell in love with Latin America,” he said in a telephone interview from his office in Cumbayá, Ecuador, just outside of Quito. “The people were so friendly.”

After returning to Austria from his post-high school trip, Resl made a big decision.

“I decided I wanted to become a geographer,” he said.

One day in 1988 while studying in Innsbruck in western Austria, he saw a poster on a wall for a seminar on GIS. Intrigued, he attended and was hooked.

“I thought, ‘This gets into computer science,'” he said.

Resl went on to earn a master’s degree in geography with a specialization in GIS from the University of Salzburg. He then attended the University of Washington in Seattle on a Fulbright scholarship to do postgraduate work toward a PhD in geography.

Then fate stepped in, precipitating a return to Latin America. Again, the young Austrian saw a note tacked up to a wall in a university building. A physician was on campus looking for researchers interested in working in Latin America. It was then 1994.

Everything had come full circle, Resl said. The doctor wanted to hire a researcher with knowledge of GIS to help him do epidemiological research in Ecuador. The work involved studying where outbreaks of malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases were occurring based on physical indicators, such as living near a pond or lake, and social parameters, such as having a home with a grass roof.

After Resl arrived in Ecuador, he soon began to branch out into other areas besides health research. He worked to create a GIS database for Quito’s municipal drinking water and sewer system. He also got involved in a foundation called DIVA, sponsored by the Danish government, which studied biodiversity in relation to cultural diversity.

Though he was becoming more fluent in Spanish, another language also served him well.

“GIS was my language to get to know people,” said Resl.

The Day the Shuar Came Calling

Resl still vividly recalls the day in 1996 when strangers showed up at his house in Tumbaco, a small town with views of the Ilaló volcano and, on a clear day, glacier-covered Mount Cayambe.

“They came from nowhere,” Resl said of the small group of Shuar men, who stood outside and stuck a spear in the ground. “I couldn’t really [figure out] what they wanted. I brought them water. Then I had them enter the house.”

Resl did not speak Shuar, and he faced a conundrum: He needed to get work done, but the men would not leave. So he had an idea. He brought out a map and, in the language of mapping, asked, “Where are you located?” They pointed to a place on the map.

“I could see they were eloquent in using maps,” Resl said.

It turned out the Shuar wanted Resl to travel to their community. Three days later, he took an eight-hour bus trip to a small airport where a charter plane (provided by a missionary church for trips the indigenous people needed to take) flew him into the Amazon. He was the only passenger on the small plane piloted by a man who said he absolutely would not stay with Resl once they arrived at their destination.

“It’s quite dangerous,” the pilot said.

“I have an invitation,” Resl replied.

They flew over a vast expanse of impenetrable trees. It was a one-hour flight that took Resl almost to the Peruvian border.

The pilot dropped him off at a small airstrip and minutes later was gone. Resl stood alone.

“It was five in the afternoon, and I waited there for a half hour,” he said. “I thought, ‘I am really lost.'”

Suddenly, the Shuar appeared.

“I was so surprised,” he remembered. “They were totally prepared. The whole community was there with a greeting ceremony.”

As darkness fell, Resl grew uncomfortable as men with spears and painted faces approached him and told him to sit down.

“I was really frightened,” he said.

A young man who spoke Spanish told him to stay awake and accept all food and drink offered.

“If they give you something to drink and eat, don’t reject anything,” Resl recalled the young man saying.

For 24 hours, Resl was observed and told to “defend yourself,” he said. He thought he was going to be on trial. All of a sudden, however, people came up to him bearing gifts such as jewelry and other Shuar crafts, as well as about a dozen spears.

The Shuar knew Resl was a geographer and wanted him to map their land. They wanted to create a map of their territory that they could give to the Ecuadorian government, and they wanted to develop a management plan for their community. Indigenous rights had long been an important issue in Ecuador, with the formation in 1986 of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador, a group of indigenous nations that worked toward gaining those rights.

Resl knew that with no roads and just jungle, mapping a territory of 220,000 hectares would be nearly impossible. So he told the tribe the work would cost them $20,000. He thought they would say no.

“But they said okay,” he recalled.

Two years passed before the Shuar returned to Resl’s home in Tumbaco.

“They said, ‘We have the $20,000, and we need to go right now,'” he said.

Resl went down to the water department where he was doing consulting work and got two GPS devices and a satellite image of the area. He also recruited a friend, a German engineer, to accompany him for the first two weeks.

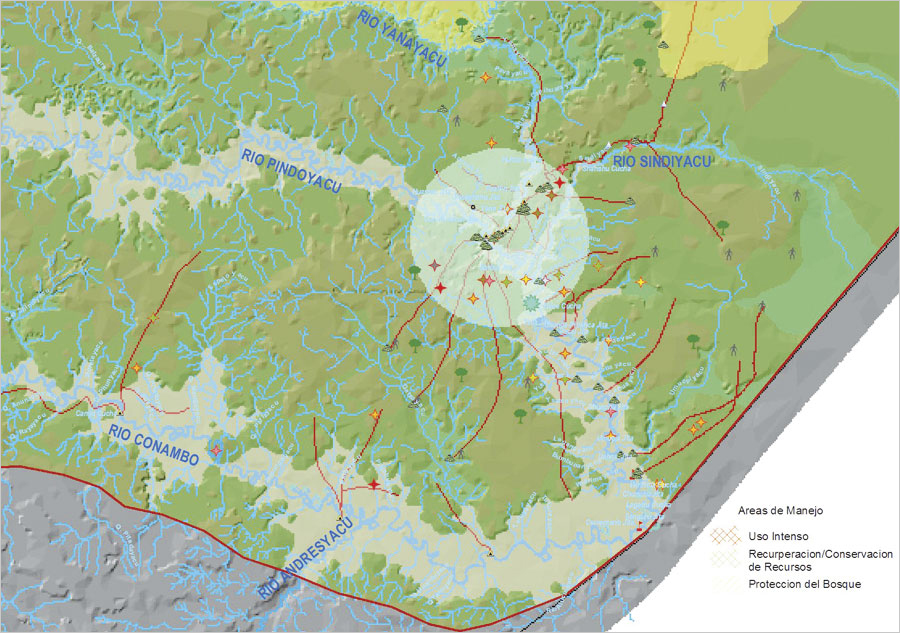

Working with a small team of Shuar men, they spent weeks trudging through the dense Amazonian jungles collecting waypoints on GPS devices. They lived off the land, eating small animals and fish. Back at his office, Resl used Esri technology to make the map of territorial boundaries using the 60 waypoints collected with the GPS devices, the natural boundaries from the satellite imagery, and biodiversity information he compiled during his time in the Amazon.

Resl later went on to do more mapping for the indigenous nations, and out of that grew AmazonGISnet. He is now the coordinator of this network of members from 11 indigenous nations who use GIS as a tool for land planning and management.

“We don’t have cars, but now we have GIS to protect our territory,” said Ankuash in Spanish while accepting the Making a Difference Award from Esri.

He told the audience that he and his people aren’t poor, but that they will be if they lose their land.

“We don’t live in the forest, we are part of the forest,” said Ankuash. “We are willing to teach and learn while we’re alive. […] We need maps so we can be strategic and careful.”

And that is what AmazonGISnet is offering. The organization trains indigenous students in GIS and other geospatial technologies. Resl said one goal is for these young people to create “life plans” for each territory that incorporate maps. The maps show how space is used within the territory, including where women grow crops, men hunt, families live, sacred and ceremonial sites sit, and environmentally sensitive land is located. The students are also embarking on a project to use Esri Story Maps to tell their stories visually and share them with the world via the Internet.

“Maps are a means to explain identity and what makes up their identity,” said Resl.

“We will maintain a record for our generation and future generations of the planet,” said Ankuash—all while trying to preserve the Amazon rain forest and expand green spaces around the world.

A Sustainable Way of Life

Going forward, AmazonGISnet plans to continue to support the indigenous people from the Siona, Secoya, Cofán, Waorani, Kichwa, Zapara, Shiwiar, Andoas, Achuar, and Shuar nations as they try to protect their ways of life.

Changes are coming to the Amazon, with increased government-backed mining, oil, and logging concerns reshaping the landscape and how people live. Resl hopes the maps that the indigenous nations are creating with the help of AmazonGISnet will give the indigenous nations a stronger voice at the planning table when land-use decisions are made.

The passing years have also brought changes to Resl’s life. Besides holding workshops for the indigenous students through AmazonGISnet, he is an adjunct professor teaching geography and GIS at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito. He is also the program director of UNIGIS in Latin America, a distance learning program that, in collaboration with the University of Salzburg, offers certificates and diplomas in GIS and post-graduate degrees in geographic information science and systems. Additionally, Resl devised and designed a modern urban cable car system that he hopes will go between Quito and the growing central locations of the Tumbaco Valley to help ease traffic jams on roadways, provide high-quality public transportation at a low cost, and decrease pollution. According to Resl, cable car transportation would also minimize fuel consumption and, in turn, reduce the effects the oil industry has on indigenous territories.

“Domingo [Ankuash] already mentioned to the city authorities that if they don’t proceed with the project soon, he would take the lead with the Austrian cable car partners to build a transport system…over the canopy in the Cordillera del Cóndor [mountain range] to connect his people and communities, avoid the construction of roads and the destruction that comes with them, and show independence from the mining companies,” said Resl.

Accepted into the community two decades ago on a lonely airstrip in the Amazon, Resl stands with the Shuar.

“They feel that their whole identity is based on an intact forest, and that this forest has to be preserved for the best of the Planet Earth,” he said. “They offer to be the keepers of the rain forest, as they have proved to be for the last thousands of years.”