Mapping Citadels and Churches with GIS

Over the centuries, the island of Kythera, nestled between the southern peninsulas of the Greek Peloponnese, has been subjected to the fortunes of war; occupation; piracy; and, occasionally, the quiet solitude of poverty and isolation. Mass migration to Australia after the Second World War was only one in a series of fundamental changes for the island.

Today, villages of the north of the island lie abandoned, the roofs of the houses fallen and the exposed rooms forests of brambles. The paths that once led to springs by the bright, running streams have been lost, and the springs, mills, and washing troughs that once sustained the communities lie derelict. But something is changing. Some villages show new life as people return to the island. Professor Tim Gregory and Dr. Lita Gregory are two people who have returned. Academics at Ohio State University with close connections to the Kytheran community, they are leading projects designed to bring to light the forgotten history of Kythera.

History is never straightforward. For an island, most of its history being nowhere near the hubs of commerce or empire building, historical records consist of accounts written by the two literate classes: the clergy and the Venetian powers that were overlords of the island after the 13th century. Written history, largely accounts of the lives of the saints and administrative data, is therefore incomplete, inconsistent, and subjective.

How did the history of the island play out for the local communities in the small, scattered towns? How did the vast majority of island inhabitants live? What was their response to the piracy, depopulation, and ruin that characterize written accounts of the island’s history? Were these accounts in fact accurate? Spatial analysis supported by geographic and cultural surveys is working to shed light on local history across the island and, by asking these questions, put the “official” accounts to the test.

The work of uncovering a forgotten history involves constant interaction between field surveys, locating and recording features, spatial analysis synthesizing information from these records, and a constant generation and testing of theory. The ability to use a suite of capabilities to compile and refine spatial data, review maps and plans presenting area-based summaries, and explore spatial relationships and distributions is critical.

ArcGIS originally came into the picture with staff of the University of Sydney, Australia, in the beginnings of this work. At this time, ArcGIS was emerging as the system of choice, under the aegis of Dr. Ian Johnson (Archaeological Computing Laboratory, University of Sydney), replacing an initial reliance on a legacy GIS. Staff currently make use of an Esri university site license provided to Ohio State University.

ArcGIS contributes in each of these areas. It provides the resources to compile digital spatial data by georeferencing scanned maps and field plans. Its basic editing and coordinate geometry capabilities allow users to integrate recorded measurements. Heads-up digitizing capabilities enable users to efficiently digitize map- and plan-based topographic and architectural features. Large-scale elevation data resulting from this work forms the source for fine-detail triangulated irregular network models and derived surfaces generated using the ArcGIS 3D Analyst extension. The ArcGIS Spatial Analyst extension explores spatial relationships and distributions making use of these results. Moreover, the ability to efficiently and rapidly integrate the processes of compiling, representing, and analyzing spatial data allows researchers to work interactively with spatial information sources that complement textual and oral sources.

Researchers have used spatial systems to support fieldwork in Kythera since 1999, when staff from the University of Sydney and Ohio State University joined to form a team under the Australian Paliochora-Kythera Archaeological Survey (APKAS) project. Over the years, this work has developed into a series of community-based projects, working in close cooperation with the Kytheran community to reveal more of the island’s past and preserve knowledge of a way of life that existed on the island until the end of the Second World War.

The baseline in the hierarchy of spatial systems is an extensive topographic dataset providing details of roads, paths, terraces, and other public infrastructure. This work, commenced by staff at the University of Sydney, is continually being extended as the geographic scope of the project increases.

This level of data forms the basis for cultural datasets comprising features and attributes associated with social and cultural activity from the earliest records to the present day. These datasets include the location and characteristics of churches and the results of diachronic (spanning historical eras) archaeological field surveys.

These two levels of data combine to form the base for spatial analysis designed to prompt, support, and test theories about social and cultural change and practice across the history of Kythera.

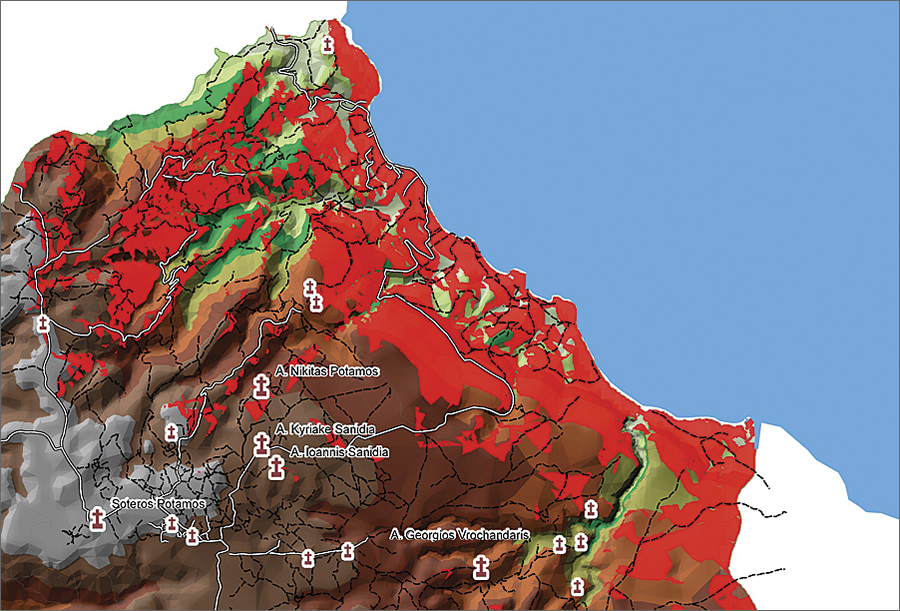

An example of this work is the use of the locations and characteristics of 58 churches spanning nine centuries to test historical accounts by determining changes in their distribution over time.

In the absence of reliable and consistent records, churches and their location in the landscape can provide insights into the locations of local settlements and the routes by which people moved, traded, and communicated.

Tradition and written sources tell us that two significant events influenced life on Kythera during the period that these churches were built and used. After the Fourth Crusade in 1250, Kythera came under the rule of Venetian interests. Less well known but more dramatically documented was the sack of the citadel of Paliochora, then capital of the island, by the Turkish admiral Barbarossa in 1537.

The mass of records resulting from the Venetian occupation of the island, largely official census records and correspondence, indicate the start of a colonial exploitation of resources that was to continue into the last century. The sack of Paliochora, characteristically for Kythera, is said to have resulted in massive ruin and long-lasting depopulation.

The study involves two analyses. The first uses a deceptively simple nearest-neighbor tool to determine the degree of clustering within the locations of churches by comparing the average distance between points with a hypothetical random dataset. The reporting coefficients provided by the tool and the ability to vary the algorithm allowed the information resulting from this analysis to be interpreted in the light of the terrain. This analysis was applied across combinations of three periods defined by the above events.

The second analysis reconstructed likely routes of communication by applying the least cost path analysis tool to link a randomly distributed set of points across the study area to two alternate centers associated with the flux of power in the island: Potamos, a market town reflecting the dominating Venetian influence, and Paliochora, the old Byzantine capital of the island.

The results of these analyses are not conclusive and indeed can never be so. However, the spatial analysis shows a trend toward greater clustering of churches in the years following the 16th century. While suggesting general changes in land use and settlement perhaps at odds with accounts of depopulation, these results prompt further research into the Venetian archives for information on corresponding changes in population and local economic conditions. The real significance of these results is the role they play within the processes of historical research.

This work is long term and tightly integrated with the Kytheran community. Its objectives will expand as more geographic and cultural surveys take place across specific areas of the island. The results of this work prompt and support new ways of looking at the past that involve a finer focus and a deeper understanding as information is gleaned from the character and distribution of features. Already, the results of spatial analysis are prompting new ways of looking at the past on the island of Kythera.

About the Author

Richard MacNeill is a senior staff member of the APKAS project and has participated in work on Kythera since 2003. He has maintained spatial systems and provided GIS analysis and data management for a variety of cultural heritage and ecological organizations and agencies.

For more information, contact Richard MacNeill or visit kythera.osu.edu.