From Individual Craft to Professional Practice

Interest in maps has stood the test of time, from the earliest days of mapmaking to the extensive use of cartography today. Unsurprisingly, the vocation of cartography has evolved throughout the centuries. It was initially a craft in which individual practitioners combined their artistic abilities with design skills that enabled them to present content in a way that others could view, interpret, and understand. Now, cartography is a specialized subject that not only sets itself apart as its own area of practice, study, and research but also contributes to the advancement of related disciplines.

How did cartography transform, and what led to its development as an academic and professional specialty? Let’s take a look at how mapmaking changed from pre-Renaissance through the end of the 19th century as new technologies emerged and the practice of making maps advanced. The next installment of this two-part series will focus on the last century through today.

Map Depictions Change from Imaginative to Precise

Early maps made prior to the age of exploration tended to center on terra incognita, or what was beyond. Drawings often depicted the universe, the heavens, and imagined distant lands. But this cosmographic view of things eventually gave way to maps that showed the world as it could be observed and, in some cases, approximated.

One reason for this, historians of cartography note, is that as tools, such as latitude and longitude, were developed to measure new discoveries, mapmakers gained greater interest in precision. Cartographic representation and design started to revolve around things like distance, time, and current conditions. Think, for example, of navigational charts and topographic maps, which are themselves instruments used to plot courses of travel and measure distances.

It also helped that, at the end of the 18th century, lithography made it possible to copy maps exactly from the original. This reduced the instance of errors, given that previously, both a map’s content and design had to be transcribed manually.

Mathematical cartography, for example, which focuses on how map projections get transformed and distorted when representing the spherical earth on a two-dimensional plane, has benefited from the accuracy that novel printing techniques, like lithography, made possible. When people use lines on a map to calculate distances, evaluate directions, and assess areas, it is important that those lines be accurate.

Geography Becomes a Proper Field of Study

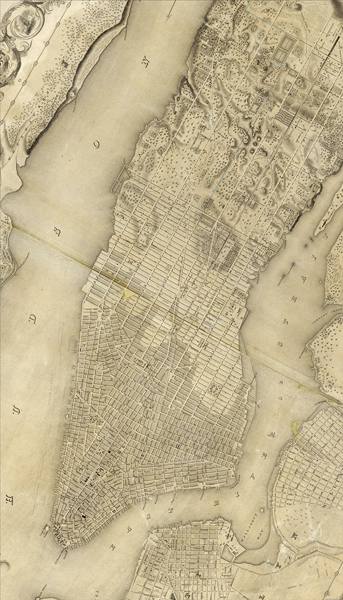

Prior to the 18th century, mapmaking was generally the domain of individual cartographers. Very early maps, dating back to the prehistoric period, were sketch-like depictions that showed the locations of objects or settlements in reference to where the illustrator was at the time. As with art during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, wealthy people frequently commissioned well-known cartographers to produce maps for them. Other cartographers created works to advance exploration and discovery, as well as to analyze results from those endeavors. And novice mapmakers produced sketches that portrayed geography that was of interest to them, much like what hobbyists and even children do today.

Mapmaking as an individual pursuit changed in the 19th century, though, when geography became a discipline. By this time, geography was often closely associated with history, meaning it helped people understand the locations of historical events. Over time, however, geography gained recognition for other uses, including figuring out how to connect neighboring settlements and delving into why something was happening in a particular location. Universities were key to establishing geography as an official field of study when they started adding specialties—like the study of different cultures, the history of cartography, or geology—to geography.

Because maps show geography, there is a natural alignment among the many specializations in geography and the different methods for visualizing and constructing representations of geographic phenomena via a map. Think about topics like physical, cultural, economic, regional, and environmental circumstances; biogeography; the climate; coastal geography; geodesy; geomorphology; glaciology; hydrology; oceanography; political, social, historical, and health issues; population density; transportation; tourism; and urban design. Now think about the techniques used to map these things, such as quantitative and qualitative methods, remote sensing, GIS, and cartography. The topics and techniques are inextricably linked.

Geographic Organizations Encourage Collaboration

Once a discipline comes into being, there is a natural tendency to organize people who share an interest in that subject area. The International Cartographic Association (ICA), founded in 1959, is a great example of this. Its establishment followed a boom in the founding of national geographic societies that began in Europe in the early 19th century. These organizations offered outlets for professional cartographers and geographers to share their experiences and publish articles and studies, which often included maps, about various geographic topics.

One increasingly available source of geographic observation was topographic maps that showed settlements, transportation, vegetation, hydrology, and hypsography. While early topographic maps were used primarily for military purposes, their versatility soon became evident for other functions like geographic exploration.

At the same time, geographic societies began storing atlases and maps, which geographers perused and used to complement their own work. These valuable documents also became a subject of research in cartography—that is, designing and constructing maps. Questions to explore included, What’s the best way to display new content? What map scale shows the desired level of detail? What mathematical projection meets a measurement need? What’s the most suitable way to display gradients of the landscape? Thus, geographers began using the maps available to them—at national geographic societies—to study the very documents they were employing as tools to further their research.

Connections Emerge Among Disciplines

In 1871, at the first International Geographical Congress in Belgium, national geographic societies coalesced in an international context. Around this time, maps and atlases were being designed, produced, and used at increasing rates.

The Statistical Atlas of the United States, based on the country’s ninth census taken in 1870, is a good example of the relationship among disciplines. Francis Amasa Walker, the superintendent of the census at the time, felt that the data collected in past censuses had been underutilized. He traveled to Paris to learn about new techniques for graphically portraying statistics and embarked on creating an atlas out of the 1870 Census results. In 1871, early maps from the census were exhibited at a session of the American Geographical Society, and Congress subsequently authorized a budget appropriation to produce the atlas. The atlas focused mainly on the results of the ninth census but also contained comparisons to all previous censuses, offering historical perspective.

Arguably, this was one of the first national atlases, since it contained maps of geographic information that extended well beyond the data presented in statistical tables. Maps of manufacturing, mining, agriculture, and disease prevalence—along with hypsometric sketches, a temperature and rain chart, and a geological map of the country—were all included in the atlas, as were topics on physical and administrative geography.

Cartography Comes into Its Own

By the end of the 19th century, then, cartography was no longer an individualistic pursuit. The expansion of technology, the growth of the new discipline of geography, and the founding of geographic societies all cultivated a surge in interest in how to make maps. Thus, cartography became a veritable professional practice and, in time, its own field of study that propelled other disciplines, including geography and mathematics, forward.