Esri founders Jack and Laura Dangermond started their company 50 years ago to help address some of the world’s most difficult challenges: land-use issues, resource management concerns, population shifts, changes in the environment, and much more. Since its founding, Esri has always stood shoulder to shoulder with its users. That’s no different when disaster strikes.

The Disaster Response Program (DRP) at Esri exists to help users respond to and enhance their GIS operations when hurricanes, fires, earthquakes, oil spills, and other crises overwhelm their organizations and demand escalated action. Assistance from the DRP comes in many forms and can involve getting users access to ArcGIS software and available data, assisting with workflows, and providing technical support.

“It’s one of our contributions back to the community,” said Ryan Lanclos, Esri’s director of public safety industry solutions and lead for the DRP. “Our core team is here to help our users when they need it most, but we also want them to know how to better prepare.”

A Deep History of Disaster Response

The first activation of the then-unofficial DRP was 25 years ago, when authorities dealing with the aftermath of the 6.7-magnitude Northridge Earthquake reached out to Esri for help. The destruction throughout Southern California was extensive: buildings cracked and crumpled, freeway overpasses collapsed, and at least 57 people died while an estimated 9,000 suffered injuries.

“After the earthquake, we had strong users reaching out to us for assistance,” said Lanclos. “We saw that we not only needed to get them help, but we also needed to understand what the impact was. Taking our expertise from the GIS and public safety worlds, we helped them do damage assessments and augmented their capabilities when they were in a really tough spot.”

Another big activation for the DRP was in New York City after September 11, 2001. When the twin towers located at 1 and 2 World Trade Center collapsed, the city’s state-of-the-art emergency operations center (EOC), located at 7 World Trade Center, was damaged beyond repair. Within a few days, the city relocated the EOC to Pier 92, a large shipping terminal on the Hudson River, and Esri was there to help.

“They printed over 20,000 maps in the weeks following the terrorist attacks,” said Lanclos. “We were honored to be in the thick of it, helping the City of New York, and the nation as a whole, respond to and recover from that incident.”

For Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the DRP provided direct aid to several agencies. It helped put together a regional database, assisted with search-and-rescue operations, supported damage assessments, and did map production.

When the BP oil spill happened in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, Esri provided the GIS capabilities to get multiple organizations with wide-ranging needs to collaborate and gain a common situational awareness.

“That was where we really saw how we could support not only traditional public safety agencies but also other types of organizations and needs all over the world,” said Lanclos.

It was then that the DRP really began to formalize. Internally, Esri established how the DRP could best respond to and prepare for emergencies, as well as how to have users activate the program when they needed it.

“Just like cities and counties activate their operations centers at different levels based on what they anticipate their needs to be, we do the same thing,” Lanclos explained. “We monitor hurricane forecasts, snow forecasts, flood forecasts, and more. We proactively reach out to users to make sure they’re ready, and we have a team on standby to field requests.”

“We are on call 24/7/365 to monitor, review, and process requests to support emergencies or events anywhere in the world,” said Brenda Martinez, the disaster response and public safety marketing specialist at Esri. “After we receive a request, it is reviewed to determine the specific need and then sent to the appropriate Esri staff members or departments for processing.”

If organizations use [the emergency management operations solution] as a road map for getting started with preparedness efforts, they can be ready for the next incident. They should do this today, even without the DRP.

The DRP has responded to countless hurricanes and wildfires, helped map disease outbreaks all over the world, and even provided assistance when multiple agencies from different countries needed to rapidly share geospatial data after Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 was downed in Ukraine in 2014.

Two years ago, the DRP experienced its busiest year on record with three major hurricanes—Harvey, Irma, and Maria—striking the Caribbean and the southern United States within about a month of one another, plus multiple devastating fires and severe flooding elsewhere.

Reacting to Emergencies and Preparing for the Next One

Unsurprisingly, the work never stops. When Hurricane Michael struck the Florida panhandle in October 2018 as a category 4 storm, Bay County sustained extensive damage. The 10-foot storm surge cut the barrier island of Cape San Blas in two and devastated the small town of Mexico Beach.

“We reached out to Bay County before the hurricane, but we didn’t hear anything until about 24 to 48 hours after landfall,” said Keith Cooke, an account executive for local government at Esri.

“They contacted us by satellite phone after the storm,” added Will Meyers, an Esri solution engineer. “They had very little communication.”

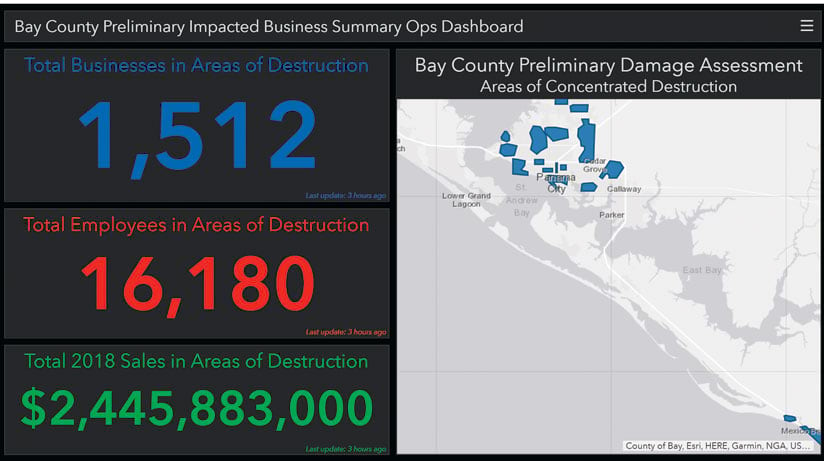

This was a rare occasion when Esri opted to deploy people on-site, so with support from the DRP, both Cooke and Meyers went straight to Bay County to help out. They assisted with general mapping, established a Web GIS presence within the EOC, and helped develop a damage assessment workflow. The two also built dashboards that officials used in their morning and evening EOC briefings, including one that showed how badly the storm had affected local businesses.

“We did some really cool stuff,” said Cooke. “But if it hadn’t been for the DRP team—with whom we had twice-daily calls—we would have been bogged down in phone calls, emails, and other minutiae in a place that didn’t have great connectivity.”

“There were so many people working on this behind the scenes, whether it was processing drone imagery, or working out logistics to get us what we needed, or just helping to connect the dots,” added Meyers. “It felt like we were sort of the middle man between a great resource team—the DRP—and the people on the ground.”

Esri’s DRP jumped into action for the November 2018 Camp Fire, too, which burned more than 150,000 acres, destroyed almost 19,000 structures, caused 86 fatalities, and devastated the town of Paradise in Butte County, California.

“I knew about [the DRP], but in the heat of the moment, everything is going crazy, and people are just pulling you in a thousand different directions,” recalled Jim Aranguren, Butte County’s GIS manager. “I think Esri reached out, or maybe I said, ‘Yeah, I need to contact them.’”

Esri DRP member Chris “Fern” Ferner jumped in to help Aranguren and Butte County manage their emergency needs.

“I didn’t even know what to ask for,” Aranguren said. “Esri was saying, ‘Do you need help with this map?’ And I’m like, “yes, yes, yes, and yes. What can you do for me?’ Esri immediately came in, contacted me, assessed what I needed, and brought in Fern to help out.”

With Ferner engaged, the DRP opened up Butte County’s ArcGIS Online organizational account, assisted with the surge of staff by giving it additional named users, and helped fix an app it was having trouble with. Interestingly, Butte County was actually prepared for a big wildfire, as well as flooding, given where it’s located—in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains, amid a lot of woodland. It just didn’t have enough resources to support the scale of this incident, which quickly turned from a wildland fire into an urban fire when it tore into the ridge town of Paradise.

“I’m trying to think now of preparing for another scenario like we experienced. What do we do?” asked Aranguren. “Our ArcGIS Online experience and presence on the web wasn’t that big. We thought about maybe migrating our services to the cloud, so that could be something we think about doing down the road. Also, what [mobile] applications do we need to have waiting in the wings? What would the schema look like? Do we have all the pieces in place for the people going out in the field to get the information they need? Let’s build those, get them set up, and have them ready to go so we will be ready if this happens again tomorrow.”

Esri’s Emergency Management Operations Solution

The DRP’s long history has led to a better understanding of how organizations can prepare for the next event.

“We have learned a lot over the past 25 years,” said Lanclos. “We want to share this with others in hopes that they can start preparing now.”

A new solution for emergency management operations provides an integrated set of tools that address common workflows related to disasters. It was developed based on the DRP’s real-world experiences.

“People typically need to think about three main areas,” explained Lanclos.

First, assess how to maintain situational awareness and how to use GIS to do it. Second, figure out how to get teams out in the field to collect data and then get it back to the EOC. Third, determine how to manage public information so citizens know which actions to take and when.

“The solution we’ve created addresses all this and is based on requirements and feedback from users,” said Lanclos. “If organizations use it as a road map for getting started with preparedness efforts, they can be ready for the next incident. They should do this today, even without the DRP.”