Wetlands, ranging from bogs and marshes to wooded swamps, are distinct ecosystems that define the natural landscape of Tennessee. They are vital to the state’s ecological well-being and scenic charm—and they yield crucial benefits to society, including filtering pollutants, recharging aquifers and streams, and providing flood storage capacity.

“Our state has a very special geology and ecology that my agency believes is worthy of protecting,” shared April Grippo, director of the Division of Water Resources at the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC).

Protecting and managing wetlands falls on TDEC, and this mission is carried out by the Division of Water Resources. In response to recent changes in federal wetland protection laws, TDEC staff now have access to an innovative tool that uses GIS technology to solve an old problem: locating all the potential wetlands in the state.

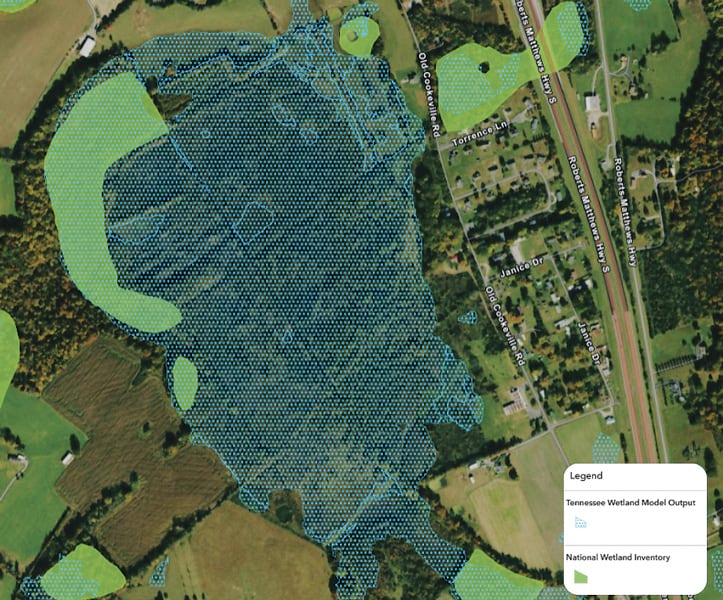

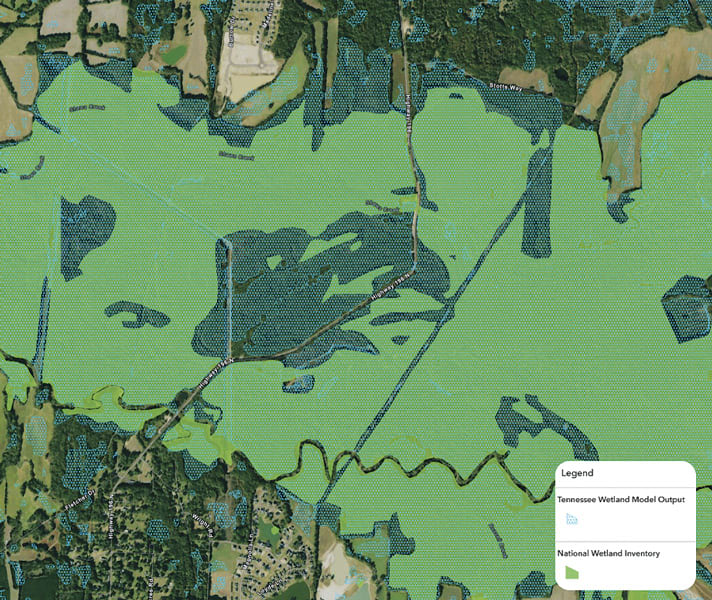

To address this challenge, TDEC staff, in collaboration with Esri partner Skytec, leveraged the Esri Wetland Identification Model (WIM), ArcGIS Online, and ArcGIS Experience Builder to develop a predictive model of the locations and extents of existing and potential wetlands throughout the state. The resultant Tennessee Wetland Screening tool allows anyone—from state agencies and policymakers to farmers, landowners, and developers—to visualize wetlands across the state, enabling informed decision-making.

Understanding Tennessee’s Wetland Landscape

State agencies have traditionally relied on the National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) dataset, which is maintained by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, for wetland mapping and regulatory needs. The NWI data within Tennessee was mostly generated via imagery from the 1980s, and only pockets of it have been updated since. This led to outdated and coarse-scale wetland data.

Since US states were recently granted autonomy to define and regulate nonfederal wetlands within their borders, it has become paramount for state agencies to find ways to update their wetland data. Access to accurate and up-to-date wetland data proved particularly crucial in Tennessee as state lawmakers considered new policies regarding wetlands and the extent of the state’s regulatory authority over them in 2024 and 2025.

“Legislators, nonprofits, and members of the public were calling us, and they all wanted to know how many wetlands were in the state and where did we get that number from,” Grippo recalled. “We knew we needed better data; a statewide number; and, importantly, [to be] able to predict where they are.”

Grippo explained that to certify the existence of wetlands, a TDEC representative or qualified consultant must conduct on-site inspections. In the past, TDEC’s reliance on the NWI has led to inaccuracies in identifying potential wetlands, causing some to be undocumented. This often resulted in property developers or owners being unaware that jurisdictional wetlands were present on their property, potentially causing delays and additional costs when they later needed to mitigate for these wetlands.

This is where the statewide mapping project came in: It aimed to provide a comprehensive, up-to-date resource for policymakers and landowners alike.

TDEC approached Skytec, which specializes in developing solutions using remote sensing and geospatial artificial intelligence (GeoAI), to model wetlands and provide a better idea of their extents and locations across the state.

Developing an Accurate and Transparent Tool

For TDEC, it was crucial that the wetlands data model incorporate a wide array of perspectives for various end users. The information needed to be equally valuable to lawmakers deciding on wetland legislation, regulatory agencies tasked with wetlands protection, and stakeholders such as residential and commercial developers, farmers, and conservation organizations.

The tool needed to help developers assess potential environmental impacts and avoid having to engage in wetland mitigation—the process of compensating for wetland loss by creating new wetlands or enhancing existing ones. For farmers, it needed to aid them in avoiding waterlogged areas and making strategic planning decisions. For conservationists, the model needed to support flood management and identify areas suitable for ecological restoration or the preservation of rare species, as well as locations with high biodiversity.

For stakeholders across the board, the tool needed to quickly identify and eliminate unsuitable sites, reducing the need for extensive field assessments.

“There are a lot of finances that go into purchasing property, and stakeholders want to know what their constraints are. So for this project, the goal was for more informed decision-making no matter who you were,” said Chris Fleming, a senior solutions engineer at Skytec.

Creating the model—a monumental task—required the seamless integration of technologies for which Skytec is renowned, including processing lidar data, integrating high-resolution satellite imagery, and developing advanced deep learning algorithms. Key to the model’s success was the training data. Fleming meticulously downloaded ground-truthed wetland delineations from regulatory reports dating back to 2011 and digitized them into a usable format. Subsequently, he incorporated Natural Heritage Network data on rare, threatened, or endangered element occurrences or habitat, as well as data from conservation groups, regional scientists, and remotely verified NWI data and delineation data.

“There’s a lot of people with a lot of information in their heads that’s not on a map,” explained Fleming. “That was the focus of our effort: We wanted the best possible training data.”

Additionally, because of Tennessee’s naturally diverse landscape, the model was broken into six broadly defined ecoregions, each with its own training data and separate model.

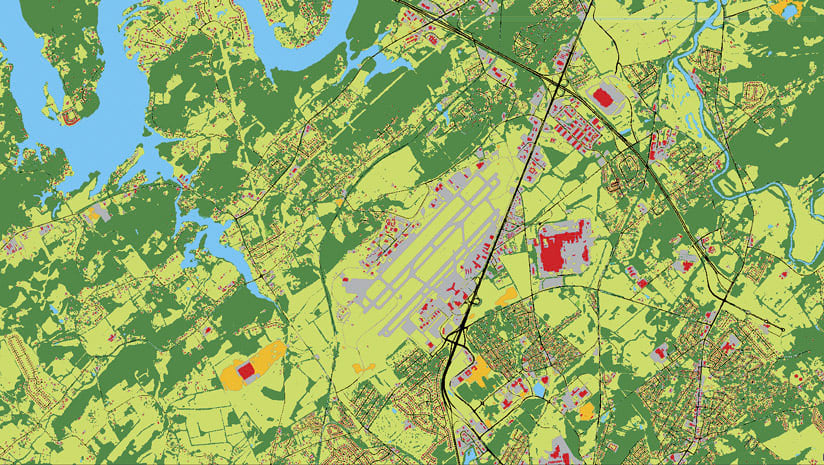

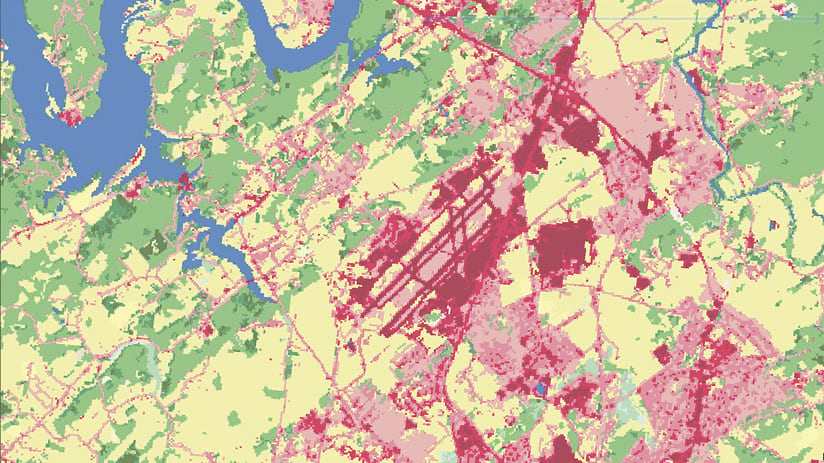

Andy Carroll, the chief technology officer at Skytec, said the timing of the project was ideal because the team had recently deployed a high-performance computing environment in the Microsoft Azure cloud. Skytec used the preconfigured ArcGIS for Microsoft Planetary Computer and deep learning models, including Esri’s Wetland Identification Model, along with a high-resolution imagery land-cover classification model, to analyze each of Tennessee’s ecological regions.

The wetland and land-cover models ran nearly nonstop for a little more than eight weeks. The result was a predicted wetlands layer and a land-cover dataset at one-meter resolution that assisted in the filtering and basic classification of wetlands across the state.

This intensive process was crucial to meeting the tight eight-week deadline set by the State of Tennessee to get this information ahead of its next legislative committee meeting.

An Encompassing Model with Many Uses

While Tennessee is the first state to create a model of this magnitude, Fleming and Carroll are confident that this process can be replicated not only for wetlands but also for other natural resources, from city canopy covers to intact riparian buffers.

“This kind of project would not have been possible just a few years ago,” Carroll said. “It was just the right time, right compute, convergence of software, and training data.”

After finishing the model, the team presented it to the public through a viewing tool built using ArcGIS Experience Builder. Skytec collaborated with Esri cartographers to create the maps and symbols used in the app.

Tennessee encompasses 26.9 million acres, and the NWI had estimated 1,065,661 acres of wetlands in the state. The model has since predicted nearly 800,000 more acres of wetlands for a total of 1,802,495 acres. Looking ahead, Grippo and her team are poised to use the model to validate their discoveries in the field and craft narratives around publicly accessible wetlands, like those within state parks.

The team’s next steps include integrating the data as a mapping layer into other TDEC workflows and addressing questions such as the number of permits issued in areas under wetland mitigation proposals. Moreover, the team aims to support the growing restoration market by identifying land with the potential for restoration that can benefit both agricultural needs and natural ecosystems.

“One agency can’t alone say something is important. We need to be able to demonstrate it, and this tool helps us tell the story about our state’s wetlands,” Grippo shared. “People are passionate about protecting these resources, but they need that knowledge, and I hope this tool becomes the first place they go [to learn].”