For many Americans, including Californians, the city of Sacramento is primarily the location of California’s statehouse. For Sacramento’s residents, it is a thriving city in its own right—by some metrics, the fourth most ethnically diverse city in the United States.

What the city’s varied communities have in common is a high engagement with Sacramento’s 311 service. In any year, the service logs around 500,000 different interactions—or one for every Sacramento resident.

Since Sacramento launched the 311 service in 2008, the city has maintained an ambitious conception of what the program should achieve. While most large- or medium-sized cities maintain a 311 program, many of them are structured as adjunct city agencies that perform a kind of ombudsman role. In Sacramento, however, 311 is conceived of as a civic connective tissue, a digital hub that links many city departments.

“It’s the front door to Sacramento,” said Maria MacGunigal, the city’s chief information officer (CIO), “the highest touch point for all the interactions the city has with the community.”

A Uniquely Expansive 311

In 2013, soon after MacGunigal accepted the job of Sacramento’s CIO, 311 was placed under her purview.

“That isn’t typical for a city’s IT department, but the 311 system was struggling under heavy demand,” she said. Much of the challenge involved the ambitious scope of Sacramento’s 311 program, which for many years has used GIS to route requests.

“We’ve always had a back end ArcGIS Server that supported geocoding and some overlay values,” said Dara O’Beirne, the city’s GIS developer. “Whenever someone submits a ticket and enters an address into the interface, it validates against our internal geocoder to ensure that it actually is a valid address within the city of Sacramento. Then it conducts an overlay and pulls attribute information from 35 different layers, such as the correct council district or police beat.”

A report of a stray dog, for example, would automatically note the relevant animal care district and notify animal care officers in the area. The ticket also generates automatic updates on the problem for the public and any agencies involved.

“Right now, that’s occurring from Salesforce, through our firewall, and into the ArcGIS Server,” O’Beirne explained.

“Most cities don’t have that kind of back end integration through all those business lines,” MacGunigal added. “It doesn’t have nearly as much of an impact on the community if we’re just taking notes and handing off the requests.”

Broadening the Scope

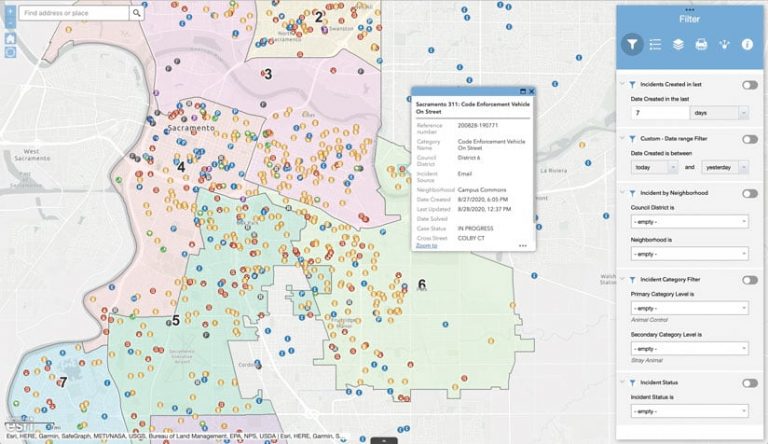

When MacGunigal was tasked with overhauling Sacramento’s 311, she wanted to broaden the program’s scope even further so it would eventually become “a foundation upon which we can build all other portal access to the public,” she said. That meant retaining the system’s GIS-enabled back end while also using GIS to improve the real-time interface. With the new setup, 311 users interact with maps, via Salesforce, that are built using ArcGIS API for JavaScript.

Consider that stray dog. The first person to report it will see the ticket displayed on the map. If someone else sees the dog and logs on to 311 a few seconds later, that person will see the same ticket and realize there’s no need to report it.

“Managing multiple reports [of the same issue or incident] was one of the challenges we were trying to overcome with this integration between Salesforce and ArcGIS Online,” O’Beirne said. “As soon as someone submits the ticket, it goes to ArcGIS Online so it’ll be reflected on the map. The next person can see the same incident at the same location. If they click on it, they open the ticket in Salesforce to find out more information.”

People can even “follow” the ticket to receive notifications when updated information is added to the ticket.

“It’s a more encompassing experience for the user,” O’Beirne said.

The system also helps city agencies better serve their constituents. “We now have data from GIS maps and layers, and we take the Salesforce data and start building dashboards around it,” said Ivan Castellanos, Sacramento’s 311 manager. “There’s even more value in the data now because it can be used to help various city departments drive their strategies and make data-driven decisions.”

The Final Challenge

“From my perspective, one of the most important aspects of this implementation is not that any one of the components of the GIS integration is brand new, but that they’re as comprehensive as they are across all the different levels of integration with the map or with the geography,” MacGunigal said. “For example, the idea that you would try to geographically understand if something had already existed or it had already been reported has been around for a long time, but we just used to do it mathematically. We didn’t actually use GIS. We used an approximation of what might be in proximity, but it became so burdensome in the system that we actually removed it at one point. So the concept was there, but the full implementation wasn’t quite there until now.”

“I think at the beginning of the project it was difficult because it was a completely unknown endeavor,” O’Beirne said. “There weren’t that many people out there who had already done this. There were one or two other cities, but not to the level that we were trying to implement.”

The final challenge was unexpected. When California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, issued the state’s first stay-at-home order in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis, MacGunigal’s team was nearing the end of several months of planning for the 311 transition. After all the work they’d put in, was the effort to push the project over the finish line while the team was scattered worth jeopardizing it?

MacGunigal chose to power through. The new 311 debuted on April 15, a mere month behind schedule. All feedback suggested that any hiccups, inevitable in this kind of launch, were minor.

The new technology worked so well that the team was able to surmount an unforeseen hurdle. Operators trained to answer calls in the 311 call center were among city employees who had been sent home. In addition to launching the new system remotely, the team also had to figure out how to make the 311 call center function remotely, a daunting task made simpler by the cloud-based architecture of Salesforce and ArcGIS Online.

“It’s not unheard of in the private sector to have call centers that have a lot of distributed locations, whether that’s at people’s homes or just multiple locations for call taking, but we’re one of the first public agencies to have a mostly remote call center,” MacGunigal said. “Everyone was remote—the development team, the GIS team, the infrastructure team—and we pulled it off without a hitch. So that was pretty awesome.”