It’s been over a century since a mob descended on Tulsa, Oklahoma’s thriving Black neighborhood of Greenwood and went on a killing and burning spree in 1921. In 18 hours, more than 1,000 homes and businesses were destroyed, and an estimated 30–300 people died. The names and burial places of the victims are still mostly unknown.

An important discovery in July 2024 brought the number of named victims to three. Through a painstaking investigation that employed innovative techniques for remote sensing and 3D mapping, the Tulsa graves investigation team located and identified the remains of C. L. Daniel in an unmarked grave at Oaklawn Cemetery.

Traditional archaeology, forensics, and genealogical methods also helped identify Daniel. The Georgia native and US Army veteran of World War I was likely about 25 years old when he died during one of the most violent racial attacks in American history.

Markers for two other known victims, Reuben Everett and Eddie Lockard, are found near Daniel’s grave. Everett, Lockard, and other documented victims are included in a 2001 report from the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921.

Over the decades, many have contributed to efforts to identify those murdered after a coverup took shape. Much remains to be done.

For current residents of Greenwood and descendants of those lost in the massacre, identifying the victims is an opportunity to rebuild family and community connections. The investigation has also ended years of silence. For too long, it was dangerous to discuss the massacre in public.

“This is something that my grandparents left this earth never realizing could ever happen,” said Brenda Nails-Alford, a descendant of race massacre survivors and entrepreneurs from Greenwood, also known as Black Wall Street. “They lost friends and neighbors that they never saw again. And here we are today talking about the race massacre openly and looking for victims as well.”

An Excavation of Hope

Tulsa mayor G.T. Bynum launched an investigation in 2018 to look for the graves of unnamed victims, based on the state commission’s report. The current investigation focuses on locating and identifying 18–21 of those victims.

“At the most human level, for all of us who have worked on this search, we just wanted to find these victims and reunite them with their families,” Bynum said at a news conference in July 2024.

The limited records that do exist to document the number of deaths include about a dozen death certificates, funeral home records, and a paid city invoice. These indicate that at least 20 adult males and one stillborn infant were buried in a segregated area at Oaklawn Cemetery known as Section 20, explained Dr. Kary Stackelbeck, state archaeologist from the University of Oklahoma and a member of the graves investigation team.

Few records exist for this part of the cemetery overall, which isn’t unusual for segregated cemeteries, according to Stackelbeck. Researchers estimate that around 1,000 people—including some victims of the massacre—were buried here over the course of 30 years, she said.

Multiple layers of fill dirt were added to this western part of the cemetery over the years to make way for new burials. Those layers have made it more challenging to locate unmarked graves.

As work continues, investigators are mapping the location of each grave using geographic coordinates. These won’t be just any maps. The project team’s digital archaeologist, Dr. Alex Elvis Badillo, director of the Geospatial and Virtual Archaeology Laboratory and Studio at Indiana State University and a digital solutions specialist at Stantec, is building a geographically accurate 3D model of Section 20.

Archaeology Moves into the Digital Realm

The digital processes developed for this project offer a novel, modern framework for archaeology, Badillo said. GIS is the unifying technology.

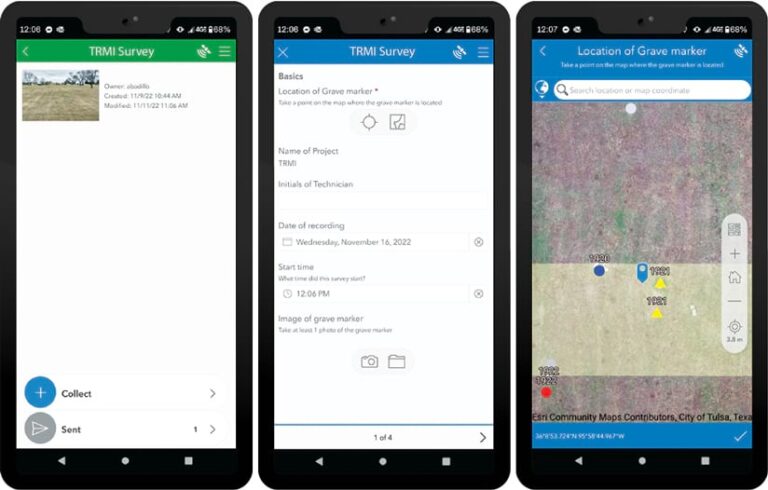

One way the project is unique is that it combines the use of ArcGIS Pro, ArcGIS Online, ArcGIS Survey123, and ArcGIS Dashboards with other geospatial technology, including GPS and a total station, an instrument that measures distances and angles. Employing all this together enables researchers to identify target areas for excavation with great precision.

Historic aerial imagery and maps, ground-penetrating radar data, and excavation data from previous years are organized and accessed in a geodatabase. Compiling this information in one place makes it possible for the team to survey above and below the ground before digging.

Filled-out Survey123 forms help the team recognize spatial patterns that reflect the likely burial routines used in Section 20. Working with local volunteers, the team also used Survey123 to complete a headstone survey in the same area. In the future, the headstone library might become available to the public in some form as a historical record.

The headstone library and forensic records are also cataloged in the geodatabase. This dynamic archive will support and expedite work as it continues in future phases—though public and/or private funding will be necessary to keep the project moving beyond its current phase.

In addition to using traditional 2D maps in the excavation workflow, the team employs structure-from-motion (SfM) photogrammetry to document the excavation in 3D. This technique takes a series of 2D photos to create accurate and measurable 3D representations of the world. One advantage of this method is that the reconstructed 3D model is wrapped in a photorealistic texture that closely mimics real-world objects.

To reconstruct the excavation in 3D, the team mounts a camera on a drone and uses a digital single-lens reflex camera to take pictures throughout the excavation process. The photos are then georeferenced using spatial data from the total station. From there, the team employs photogrammetry software to make the 3D models. There is one model of the entire cemetery, as well as models of the excavated trenches and areas where heavy machinery was used to remove large amounts of dirt that covered the burial plots.

Each burial plot is carefully documented using SfM photogrammetry methods. The result is a 3D geodatabase where the digital burials are shown within a large trench under a digital representation of the cemetery surface. Each 3D model retains its real-world coordinates and can be viewed and measured in ArcGIS Pro or ArcGIS Online.

Lastly, to make it easier to collaborate across teams, a dashboard built with ArcGIS Dashboards has been essential, according to Badillo. The dashboard allows team leaders to review files in the geodatabase—clicking through drone imagery, for example, to see the project’s progress over time or images of excavated trenches.

“The dashboard is typically the most useful to people who are not specialists in GIS,” said Badillo. “So I try to put a lot of effort into developing the dashboard and even the web scene. They can very quickly look at it, but if they need me to, I can open it up on the iPad and show them right there in the field to help with decisions.”

Reconnecting Fragmented Threads of Local History

Finding the graves of massacre victims is one of many stages of the investigation. Identifying those exhumed could take much longer—perhaps decades. It requires matching DNA samples to those of a living relative who has submitted DNA for ancestry analysis or other purposes.

Intermountain Forensics is the laboratory assisting the city with DNA analysis and helping create genetic genealogy profiles. The project leaders—Stackelbeck and forensic anthropologist Dr. Phoebe Stubblefield from the University of Florida—have also welcomed Nails-Alford, a community liaison, as a member of their team. Nails-Alford enriches their work in ways that are both personal and meaningful.

“She leads us in our morning prayer and our ending day devotions,” Stackelbeck said. “She has excavated with us. She has screened dirt to look for artifacts. She has helped us monitor the backhoe work while we’re looking for the graves. She has done all of that.”

Being on-site and learning about investigation strategies has given Nails-Alford a greater appreciation for the complexity of the work required to identify victims.

“My great-grandmother is buried here at Oaklawn somewhere, but I may never know where,” she said. “We’re already giving a family the opportunity to know who their loved one was and to give them that opportunity to memorialize them in the way that they see fit. And for us to be working towards giving other families that opportunity means so much to me.”