I’m a firm believer in science in the service of the public. Our work as geographers and GIScientists should make the world a better place. And yet the way I and many others were trained assumed that it was the results of our work that mattered, not the process by which we gathered our data in the first place.

The common practice (often described as helicopter or parachute science) has been to arrive at a field site, extract needed data, and leave without building reciprocal relationships to the communities and landscapes being studied. Researchers benefit via publications and grants but have not been expected to give anything back in return. And because scientists centered their work on Western knowledge and training rather than on thinking collaboratively with local and Indigenous knowledge holders, their results were less robust than they could have been.

Happily, the tide is starting to turn. Geographers and GIScientists are embracing a range of approaches that engage more reciprocally with the communities we study by working together to develop questions, conduct research, and analyze results; protecting communities’ right to control what happens to data produced about them; and even honoring their right to refuse that they or their biophysical environment be studied at all.

These practices go by many names, such as participatory action research, public science, co-production, participatory GIS, and data sovereignty. Some are relatively new; others have long histories. They extend across geographic fields, from geomorphology to GIS and from climatology to cultural geography. Students and early-career scholars are increasingly seeking these reciprocal approaches in hopes of making more meaningful contributions through their work. The implications of this extend into many geographic fields and practices in the public and private sectors, from community planning to large industrial site decisions and from environmental restoration projects to public health programs and food systems.

GeoScience with an Open Hand

Some of the reciprocal scholarship that I find most inspiring is directly in or enabled by GISciences. For example, the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project is an all-volunteer nonprofit collective that works with low-income communities to illustrate the extent and impacts of evictions and work to prevent them. Operating mainly in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, and New York City, volunteers work with residents who are at risk of eviction to visualize data and tell the stories of evictions, successful interventions, and active resistance to displacement. Likewise, as part of the British Columbia Caribou Project, three geography students used ArcGIS StoryMaps to call out state subsidies for oil projects that further imperiled endangered woodland caribou by funding oil-well digging in protected habitat areas.

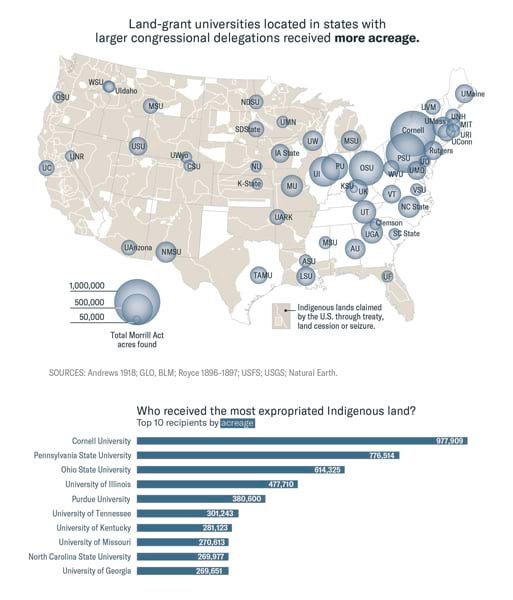

A third example comes from Dr. Margaret Wickens Pearce, 2024 winner of the Stanley Brunn Award for Creativity in Geography, one of the most prestigious awards the American Association of Geographers (AAG) bestows. Pearce is a Citizen Potawatomi Nation member and cartographer who engages with Indigenous communities to produce beautiful and thought-provoking maps that recover and celebrate Indigenous languages, illustrate settler colonialism impact, and show the relationship between land expropriation, Indigenous dispossession, and the US system of land-grant universities.

Protecting and Valuing Reciprocal Work

Despite the intellectual and political impact of these and many other community-engaged projects, reciprocal scholarship is undervalued in geography, both inside and outside academia. Examples of this work are lauded as publicly relevant scholarship, but often do not count when it comes to promotion or hiring decisions. In academia, reciprocal scholarship is most often classified as service rather than research, and thus does not count toward the work that graduate students are required to produce to earn advanced degrees and that faculty need for tenure and promotion. Similarly, public agencies and nonprofit organizations rarely combine effective science communication and community-engaged environmental management with their internal promotion processes.

In response, AAG is working to support individual geographers and GIScientists who want to strengthen their public engagement skills via the Elevate the Discipline program while promoting and protecting reciprocal scholarship more broadly via the AAG Public and Engaged Scholarship Task Force. The task force’s goal is to protect and value reciprocal scholarship by developing the following:

- Recommendations for how AAG can reward and protect public and engaged scholarship (PES) by geographers and GIScientists inside and outside academia

- Sample policies and best practices for incorporating PES in hiring, personnel evaluations, theses, dissertations, and tenure and promotion cases

- Guidelines for external reviewers, funding agencies, and others evaluating PES

- Best practices for overcoming common institutional barriers to PES, such as compensation for community partners

Strikingly, the task force has found no examples of policies or practices for valuing and protecting reciprocal work in hiring and personnel reviews outside the academy in public agencies, nonprofits, and the R&D sections of private companies where many geographers and GIScientists are employed.

I would love to see the GIScience community take this on. For example, guidelines from universities such as the University of California, Los Angeles could be adapted to nonacademic workplaces. To help leaders in public agencies, nonprofits, and private businesses understand why reciprocal scholarship is worth supporting, readings from books such as Faith Kearns’s Getting to the Heart of Science Communication can help explain the effort involved in working reciprocally and its enormous benefits in building community trust and engagement.

GIScience already has a strong track record of reciprocal scholarship. It would be great to deepen that, and to better protect it.