How many Indigenous Nations and communities can you name? Who are the Indigenous Peoples original to the land you now reside and work on?

I have always been surprised by how few nonindigenous peoples are able to answer these questions. With thousands of Indigenous Nations existing throughout Turtle Island (North America)—and more around the globe—how is it possible that most settlers cannot name more than a handful of Indigenous sovereigns?

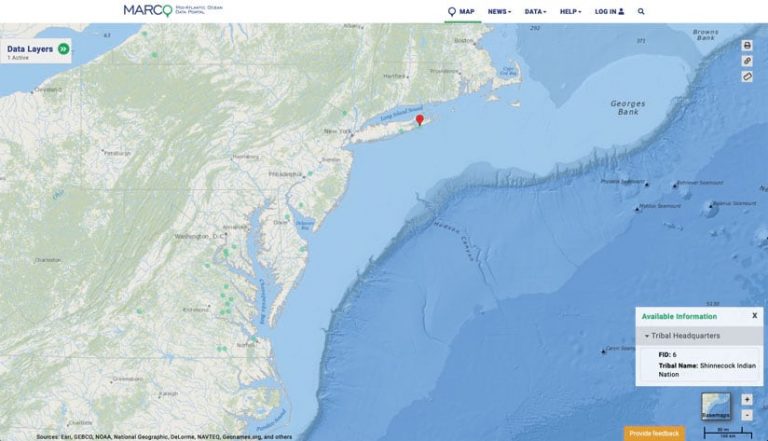

In 2014, while serving as a tribal coleader for the former Mid-Atlantic Regional Planning Body of the United States’ National Ocean Council, I was confronted, again, with this phenomenon of Indigenous invisibility while reviewing our Mid-Atlantic Ocean Data Portal. In examining this digital mapping interface—which federal and state agencies, fishery management councils, and broader stakeholders throughout the United States regularly use—I noticed that Tribal Nations were absent from the map.

I realized in that moment that the absence of Indigenous participation in broader ocean planning forums has a deep connection to our erasure in maps. If we are not on maps, we usually don’t have a seat at the table. And there is no justice for Indigenous Peoples if we are not participating in the decision-making that affects our territories.

We need maps by Indigenous Peoples, for Indigenous Peoples. Moreover, existing GIS ecosystems need to be designed in ways that support Indigenous data sovereignty and visibility—for the benefit of all.

Through courageous conversations and dedicated allies, we were able to update the Mid-Atlantic Ocean Data Portal to reflect the diversity of Indigenous Nations in the region. But despite that success, as an environmental scientist and policy maker, I continue to be confronted by the erasure of Indigenous Peoples from policy tools and data, including maps. This erasure has far-reaching consequences that affect our shared sustainable future on this planet.

Unfortunately, contemporary maps are the physical manifestation of an inherited legacy of intellectual colonialism. For centuries, maps, mapmakers, and the discipline of cartography have contributed to (or, through acts of complacency, encouraged) the colonization and dispossession of Indigenous Peoples’ lands, territories, and resources. This has essentially prevented us from exercising our sovereignty and Indigenous rights as protected by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Not only have our territories been erased from dominant mapping regimes, but our languages are absent as well. Yet the inclusion of Indigenous languages in mapping is critical for reconciliation and peace building, since language is, of course, key for communication and education.

Indigenous knowledge systems and science are diverse and dynamic, built on observations accumulated over millennia and passed on through a complex system of intergenerational transmission. Even the orientation of maps is being challenged by contemporary Indigenous cartographers, as seen in the Decolonial Atlas project “The Great Lakes: An Ojibwe Perspective”, wherein Ojibwe speaker Charles Lippert and cartographer Jordan Engel have digitized Anishinaabe geospatial knowledge of the Great Lakes and oriented the compass to the east (or waabang in Ojibwe), the direction in which the Anishinaabe traditionally orient themselves.

Forms of Indigenous decolonizing cartography like this offer a glimpse of what decolonized GIS mapping could look like in the future. And the future is now.

Our borders have been made so invisible that many people pass through Indigenous territories, including reservations and reserves, and never realize that they’re in Indian Country. (Indian Country is a legal term that refers to all land in Indian reservations and Indigenous communities throughout the United States. The term is used colloquially among Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island to refer generally to Indigenous lands, waters, and territories.) This erasure has severe implications and complications for transboundary cooperation among Indigenous and nonindigenous peoples and priorities as we chart a path forward in our current climate crisis.

In addition to being erased from maps, Indigenous Peoples also have to contend with the continued use of derogatory place-names. For example, the word sq**w is a disparaging reference to an Indigenous woman, yet it is still used in the names of cities, towns, geographic landmarks, and businesses across the United States. As Indigenous communities face an epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, the continued use of derogatory terms like this condition the world to see Indigenous female bodies as inherently violable. And when place-names like that are captured in maps, they further socialize the public to believe in myths such as the “vanishing Indian,” which purports that Indigenous Peoples have disappeared, and to keep promoting colonial philosophies like the Doctrine of Discovery, which, for centuries, has justified the seizure of Indigenous lands.

In recent months, with social justice movements around the world toppling monuments and changing controversial holidays, we also saw the renaming of some disparaging place-names—though there are still too many on our maps. Calls for justice are being amplified within projects like the Land Back movement, which seeks the return of ancestral territories to Indigenous jurisdiction. And Colorado-based High Country News recently published an investigative journalism series exposing American universities that have participated in land grabs of Indigenous territories, causing intergenerational trauma to Indigenous Peoples.

So where do we go from here? Despite cartographic atrocities committed against Indigenous Peoples, we can chart a new course with the help of the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) and its newly developed CARE Principles. These principles—which revolve around the ideas of collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, and ethics—advocate for Indigenous data governance and are directly applicable to GIS data and mapping.

To decolonize GIS mapping practices, consider the following questions:

- How can you ensure that GIS ecosystems are designed and function in ways that enable Indigenous Peoples to benefit?

- Are Indigenous Peoples in control of their own GIS data? Do they determine the ways in which their geographic indicators are represented?

- How are you fulfilling your responsibility to not only ensure that Indigenous Peoples are represented in mapping but also foster positive relationships that lead to more mapping collaborations with Indigenous Peoples?

- What steps have you taken to protect Indigenous rights and well-being across GIS ecosystems and ensure justice for all?

These are not easy questions to answer. But it is imperative to face them if we are to create a new mapping ecosystem that achieves the following goals:

- Promotes equitable outcomes for our collective benefit

- Respects and recognizes the rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Champions Indigenous languages and world views and builds capacity for Indigenous cartography

- Endows future generations with GIS ecosystems that benefit everyone

Indigenous Peoples need everyone to commit to the difficult work of decolonizing our GIS practices so we can create a world full of mapmakers, data scientists, and policy makers who are also data CARE-givers.