As a trained biologist focused on conservation, Joe Lemeris, the GIS and data manager for the Heritage Trust Program within the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (DNR), has used GIS to map wildlife extents, monitor endangered species, manage habitat restoration projects, and more. Yet where he really shines is in employing geospatial technology to transform how whole organizations operate.

“Joe is relatively young in his career, but he gets it,” said Sunny Fleming, Esri’s environment and conservation industry specialist. “He has an intuitive sense of strategy and the value of GIS, and he translates that into developing useful tools not only for the benefit of South Carolina’s natural resources but also for the conservation field at large.”

After attending Boston University, where Lemeris majored in biology with specializations in ecology and conservation, he enrolled in the Master of Environmental Management program at Duke University.

“It was at Duke that I was first exposed to GIS,” he said. “One of the first meetings we had was in the career office, and they said, ‘We have a strong GIS program here, and it’s probably one of the more marketable skills you could acquire. We encourage everybody to at least take the intro class.’”

So that’s what Lemeris did. While he found the course challenging, he liked how mapmaking brought out his artistic side and was amazed at how widespread the applications of GIS were.

“I thought, ‘Wow, you could do so much with this’—and specific to the areas I was focused on: ecology and conservation,” he recalled. “That’s still my passion, and the fact that I can apply GIS to solve those types of problems is what really led me down this path.”

Lemeris earned a certificate in GIS while he got his master’s degree. He put his geospatial skills to use right away when he interned as a GIS analyst with the N/a’an ku sê Foundation in Namibia, where he studied the translocation of cheetahs and leopards that were causing problems for local farmers.

“We would take the animals, put a radio collar on them, and release them into protected areas that weren’t near as much human activity so that, in theory, they wouldn’t be problematic anymore,” said Lemeris.

He parlayed this experience into his final master’s degree project, developing a solution called the Carnivore Translocation Suitability Tool (CaTSuiT) to analyze the best places to put big cats when they’re taken away from a problem site.

“The tool took the cat’s original location, along with survey data from landowners, and spit out a raster of potentially suitable habitat in Namibia for that particular cat,” Lemeris explained.

He and a colleague from the foundation published a few papers together that employed CaTSuiT. And after graduation, Lemeris continued this work by becoming the intern coordinator for the National Geographic Society’s Big Cats Initiative at Duke.

“We worked on some cool projects. One of them was redrawing the range maps for leopard distribution worldwide,” Lemeris said.

The finer-scale range maps that Lemeris and his team members produced led, in part, to several subspecies of leopards being declared more endangered than previously thought. This can help with conservation efforts to preserve their habitats.

“It was pretty amazing to have that kind of impact,” Lemeris reflected. “The intersection between humans and conservation is unavoidable, so you have to figure out a way to balance that. And GIS is the perfect tool for that.”

After a year and a half with the program, Lemeris got a senior biologist job at the South Carolina Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism.

“The job description really didn’t have any GIS in it, per se, but as soon as I got there, I recognized that GIS could be used to create better, more efficient processes,” he said. “I was responsible for things like habitat restoration, survey design, and monitoring endangered species in the parks. All that has to be mapped, so we started beefing up our software.”

With support from the agency’s chief information officer, Lemeris encouraged his colleagues to upgrade their GIS and take advantage of newer technology, such as ArcGIS Online and ArcGIS Pro. They began making web apps and building ArcGIS StoryMaps stories to enhance public engagement.

“We were showing where prescribed burns would happen,” said Lemeris. “Our historian also made some fascinating [stories] about the cultural significance of our parks.”

Lemeris and his team earned a Special Achievement in GIS (SAG) Award from Esri for their use of cloud-based GIS to make data collection and analysis more efficient and accessible. Around that time, Lemeris moved into his current, GIS-focused role at the state’s DNR.

“I’d spent so much time investing in my GIS expertise that I felt like I didn’t want to lose it,” he said. “I saw that there was an opening for a GIS analyst position at the DNR to revamp the state’s heritage database with support from the Department of Transportation [DOT], and I thought that sounded like a perfect fit.”

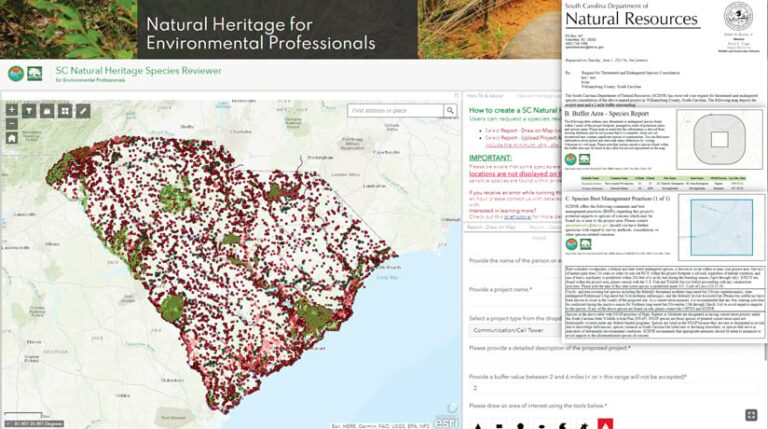

While the DNR had been actively managing its heritage database—which catalogs the sate’s natural and cultural resources—the data backlog had grown, and a lot of species records were missing, according to Lemeris.

“There was data everywhere, but it wasn’t getting updated in a central location, and there wasn’t an easy way to share anything,” he explained. “DOT [staff were] experiencing issues where, if they were redeveloping a road or building a new bridge, it would cost them extra time and money because they’d find out that there was, say, a rare plant or freshwater mussel in the stream nearby—something that they never knew was there. But they would have known had the data been kept up and easily attainable.”

Lemeris was hired to work through the data backlog and figure out how to make heritage data available to anyone who needed it. One of the first things he did was sign up for the Esri Advantage Program (EAP).

“Originally, our grant indicated that we were going to hire an in-house developer to build our system, but I was worried about what would happen when the developer left,” he said. “The Advantage Program was actually less expensive than our alternative options.”

In his first few years at the DNR, Lemeris spent a lot of time cultivating relationships with other biologists, foresters, and anyone else who could benefit from expanding their use of GIS.

“Within his own agency, Joe quickly proved the value of GIS for a wide variety of environmental workflows,” Fleming pointed out.

He showed colleagues how to use GIS to collect data more efficiently, which also ensured that the information flowed into the heritage database.

“I would show them how using ArcGIS Survey123 could save them data entry time and allow for data sharing without having static copies floating around,’” said Lemeris. “After many meetings and presentations, people began thinking about how they could use GIS in their own work—and they started reaching out to us.”

This process has worked very well for Lemeris and the Heritage Trust Program—not only in terms of buy-in for GIS but also because it makes a wide range of data very accessible.

“For example, our herpetologist has technicians running all over the state collecting data on reptiles and amphibians, and every six months to a year, I’ll go in and pull the rare species data and put it in our database,” said Lemeris. “Then the data is available for everyone who needs it to protect those species.”

The system that Lemeris and his team have developed, which includes publicly available web apps, lets both internal and external stakeholders access heritage data on a self-service basis. So everyone, from private developers to employees at the DNR, can get the data they need when they want it, curtailing manual processes and cutting down on the time it takes to retrieve the data.

“The return on investment is huge,” said Lemeris. “It’s helped with data sharing across agencies, and people trust that they’re getting authoritative data.”

This work earned Lemeris and his current team a SAG Award in 2021. It has also inspired other state DNRs and natural heritage programs that collaborate with NatureServe, which consolidates data from these programs across North America.

“I could not do what I do without the support of everyone at DNR who encourages us to charge forward in the progressive way that we do with GIS,” Lemeris reflected. “There’s a growing sense here that if we put our data to use spatially, it will generate powerful solutions to help care for our state’s natural resources.”