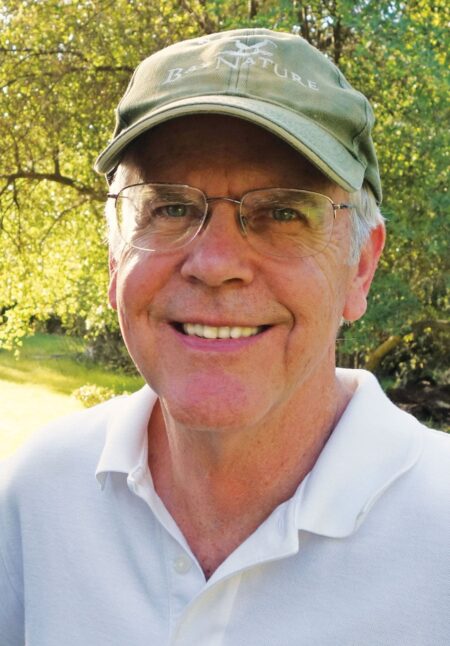

As a white-water rafting guide in California in the early 1970s, Larry Orman gained a profound understanding of how environmental activism works—and sometimes doesn’t.

Well before he built up Greenbelt Alliance or founded GreenInfo Network, he fell into this adventuresome job at the suggestion of a roommate.

“We were trained in brutally cold weather,” Orman recalled. “It was the best thing ever.”

But one of Orman’s routes, along the Stanislaus River, was being threatened by a dam. A spectacular stretch of rapids was going to be inundated. As construction on the dam started, a new breed of environmentalists was taking form—and Orman was one of them.

“We fought the building of that dam, but we lost” he said. Nevertheless, “it gave me a huge collection of friends and political understanding”—both of which Orman has relied on throughout his influential career in mapping and protecting open spaces.

A Visceral Dynamic

Orman grew up on the edge of Mission Valley, California, an area just outside San Diego proper (at the time) that was known for its dairy farms. He played in the valley’s open spaces and enjoyed visiting downtown San Diego, which was actually cohesive in the 1950s.

But then, the city put a shopping center in Mission Valley. According to Orman, this gave the valley its own core, which caused downtown San Diego to fall into disrepair.

“It completely destroyed Mission Valley, from my point of view, as a natural area,” he said. “And downtown San Diego was an absolute wreck. That dynamic was visceral for me.”

After high school, Orman moved north to attend UC Berkeley. While studying environmental design and architecture, he spent a year in Germany living in a relatively small city that was surrounded by farmland. He marveled at being able to walk all over town and then step straight into the greenbelt.

“That alternative to what San Diego had done got really imprinted in my brain,” he said.

When Orman returned to Berkeley, he took a class that required students to work on one project for the whole term. Orman chose to help a group of local citizens fight a development down at the waterfront.

“We held off development proposals tooth and nail,” he recalled. While it took 20 years of community activism, that development site—which was slated to become a shopping center—is now a state park.

“I ended up learning a lot,” Orman said. “I have a background that was ripe to be catalyzed by something like that shopping center, and that thrust me into city planning.”

Orman got his master’s degree in city and regional planning from UC Berkeley. He then forged a career that centered on setting the agenda for regional planning and conservation—first in the San Francisco Bay Area, next throughout California, and now for many places around the United States.

Creating the Geography of an Issue

After graduate school, People for Open Space hired Orman as its first paid employee. Over the next 19 years, Orman built that organization—which became Greenbelt Alliance—into a force for open space and land conservation in and around the Bay Area.

“When I started with this very small organization, we wanted to take on the big question of how to define a whole greenbelt for the Bay Area,” Orman said.

The organization didn’t get all the funding it needed for that, so Orman and his colleagues took on agricultural land instead.

“We said, we’re going to give that use of open space a voice and talk about what should be done to protect it,” he recalled.

They spent two years learning about farmland—including where it was.

“Nobody had a clue!” Orman exclaimed. “We had to draw our own maps. We had to create the geography of the issue to show people its extent.”

Greenbelt Alliance also devised the idea of identifying land that was at risk of development.

“We decided to talk about all the lands that are unprotected and under pressure of being developed,” Orman said.

The organization started doing risk mapping. This is when Orman began using GIS.

“Our map ended up showing areas of high and medium risk over large parts of the Bay Area,” he said. “Our point was, this isn’t all going to be developed, but until we take away some of these risks, any of it could be.”

This project, which showed that the Bay Area had too much land up for grabs, got media coverage. According to Orman, it helped constrict development around San Francisco. Although the area has been booming in recent years, it hasn’t seen much massive sprawl.

“The mapping helped with that,” said Orman. It also made him realize how important it was to have competent, compelling visuals to tell a story.

“I taught myself GIS. I’m not an expert by any means,” he said. “The thing I learned is, you can have the best technical understanding in the world, but if you don’t know how to communicate in the public-interest realm, you’re never going to make an impact.”

A Long Arc of Work

This thinking inspired Orman’s next project: founding GreenInfo Network to help nonprofit organizations use GIS. The technology was becoming more democratic, moving from workstations onto personal computers, and data was more widely available.

“My thought was that I’d get nonprofits going with GIS, and then they’d take it and run,” said Orman. But nonprofits didn’t have the resources to get great at GIS. So GreenInfo Network became a consulting organization that helps a range of public-interest groups better visualize and communicate their ideas.

“The timing was great,” said Orman. “People were extremely interested in visualizations.”

While at the helm of GreenInfo Network, Orman and his team developed the California Protected Areas Database (CPAD), a GIS inventory of all the protected open space in California that’s owned by various agencies and nonprofits. The project was part of a long arc of work for Orman, evolving out of his efforts to create a database of all public lands in the Bay Area and ending up as a major impetus for the United States Geological Survey’s (USGS) Protected Areas Database of the United States (PAD-US), which Orman helped develop.

“That whole trajectory shows how Larry has worked, and led others to work, incrementally,” reflected Dan Rademacher, the current executive director of GreenInfo Network. “Thirty years ago, people might have wanted a national database of parks, but that was really hard to do then. One of the ways to get there, though, was to make tangible progress where you could. He led the creation of the Bay Area Protected Areas Database. It wasn’t ever perfect, but it amassed data and got jurisdictions talking to each other. And it always got more useful over time. Then that grew into CPAD”—and beyond.

Reveling in Old Open Spaces

In his 20 years as executive director of GreenInfo Network, Orman worked on countless projects that helped shape conservation all over California and the United States. At the end of 2015, he decided to step down as executive director and hand the organization over to Rademacher to foster continued growth in the digital age.

Orman is now a senior fellow at GreenInfo Network, working on projects of his choosing, including PAD-US.

“One of the other projects I’m working on is an archive site for the Stanislaus River,” he said, referring to the river that was dammed when he was younger. “I’m working with people I knew from those days to develop a really wonderful website that’s going to be an archive to remember what it was like.”

While he’s never been back to the river itself, he revels in his memories of that open space.

“It was really one of the more exceptional places in California that we just couldn’t save,” he reflected.

Although it has been a bit of a tough project to work on, Orman concluded that “setting up before-and-after images really helps reinforce what I knew was there.”