With GIS and a Green Infrastructure Model, Government Finds Scientific Support for Strategic Conservation

To mitigate the effects of climate change and extreme weather events, governments at the state, regional, county, and municipal levels must understand why these events occur and how their impacts can be prevented in the long term.

Following a devastating storm in Richland County, South Carolina, decision-makers there are gaining a better understanding of how people’s choices alter natural environments—and how these changes affect everyday life and future generations. The county is now testing a new approach to bolster the region’s sustainability. By combining GIS with a green infrastructure methodology, Richland County is gaining a scientific understanding for how to create a more resilient, economically viable, and smarter place to live and do business.

The Long-Term Consequences of Disaster Recovery

In October 2015, a two-day storm caused by Hurricane Joaquin swept across South Carolina, leading to devastating flooding, more than a dozen deaths, and the destruction of critical infrastructure. The state recorded $12 billion in losses with up to 160,000 homes damaged.

Richland County was hit worst. This once-in-1,000-years event dumped two feet of water in some areas of the county, killing nine people and threatening the drinking water. Schools, businesses, and roads remained closed weeks after record rainfall and dam failures occurred.

The historic flood urged decision-makers to ask serious questions. Why did flooding occur in this area? What caused the dams to fail? What can we do to prevent this from happening again?

For some, however, the answers had been evident for a long time.

“Flooding is a natural event, but the impacts we experience are caused by humans,” said Quinton Epps, director of the Richland County Conservation Department. “We build in the areas that are flood prone. Very often, we change the areas in dramatic ways…that increase flooding impacts. These are things people have known for hundreds of years.”

Homes built near bodies of water, for example, are appealing and tend to have higher property values, but they are predisposed to flooding. In Richland County, regulations require developers to build houses that would accommodate a 100-year event, meaning the structures must be built two feet above the base of a potential flood. But although subdivisions meet current regulations, they are still in danger of being damaged by more severe floods like the county saw during its 1,000-year event.

As the person in charge of securing properties and funding for conservation efforts, Epps also acquires easements to help avoid disasters like the 2015 flood. He spearheads projects to connect people with nature as well.

The job is no easy task. Success relies heavily on factors that are out of his control, such as the availability of land, willingness of property owners to sell or donate easements, and political interests that drive funding and development decisions.

After Hurricane Joaquin, Epps advocated to fund easements in flood zones to ensure that the land is never developed. But Richland County allocated its limited grant dollars from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development elsewhere—namely, to rebuilding homes and roads.

“The way people look at disaster recovery tells the story of how we don’t look at long-term consequences,” Epps said. “Do we have money to fix the problems of the last 50 to 100 years of development? No. But we can try to prevent history from repeating itself.”

To Epps, most disaster recovery and development strategies focus on rebuilding and extending existing man-made infrastructure. However, these strategies dismiss a critical component of creating a safe and livable community: green infrastructure.

Using GIS to Identify, Map Critical Resources

Several months after the storm, Epps attended a workshop hosted by Karen Firehock of the Green Infrastructure Center, where she presented her methodology for developing and implementing a green infrastructure plan.

The idea was appealing—use data, science, and GIS to identify and map the critical resources that make each community unique and that also serve a vital purpose, such as rivers, trees, and hazard areas. Then, prioritize the ones that should be preserved and roll out a plan that protects, restores, and connects the landscapes.

With Richland County still reeling from the flood, a green infrastructure model could do more than connect people with nature; it could also help win executive buy-in for conservation projects that safeguard wildlife habitats, protect people and property from future harm, and boost the economy. By using GIS to assess all the county’s features that the community deems valuable, Richland could explain the importance of green infrastructure in a more scientific way.

“We could provide a rational basis for conservation efforts not tied to politics or opinions,” Epps said.

He was inspired to formulate a green infrastructure plan that would enable the county to plan smarter, but he couldn’t do it alone. Based on Firehock’s guide, Evaluating and Conserving Green Infrastructure Across the Landscape, he knew one person would be the key to developing the model—Brenda Carter, GIS manager for the planning and development services department at Richland County.

A Green Infrastructure Plan for Richland County

When Epps approached Carter to help with the project, she read through the guide and did additional research online. Carter was familiar with the concept of green infrastructure, given her 32-year career in GIS. And soon, she knew why Richland County needed a green infrastructure plan and why GIS was such a critical component.

“Reading through everything made me realize that this was something really, really important for all counties and for all people—especially after our county had just suffered a great flood,” Carter said. “I started seeing the connections as to why the flood could have happened and why we needed to do something about it.”

Thus, the planning and conservation departments formed a partnership to bring green infrastructure planning to Richland County. Carter outlined goals and developed the entire green infrastructure blueprint. She began by identifying four goals:

- Improve water quality by providing a buffer to help prevent runoff and erosion and reduce pollutants

- Maintain forested land cover to facilitate recharging groundwater aquifers for drinking water

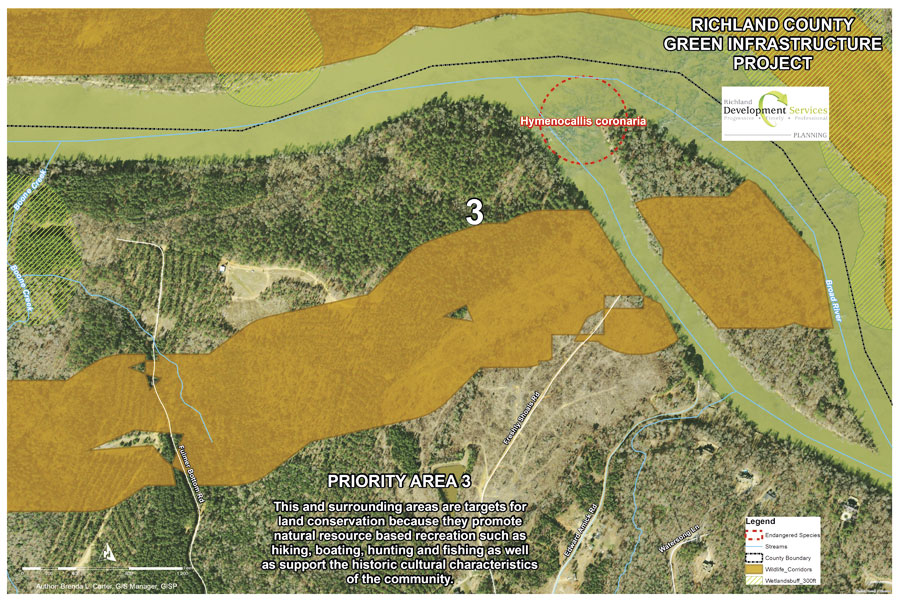

- Preserve and promote natural resource-based recreation, such as hiking, bird watching, hunting, and fishing

- Conserve community character and heritage by protecting a historic landscape.

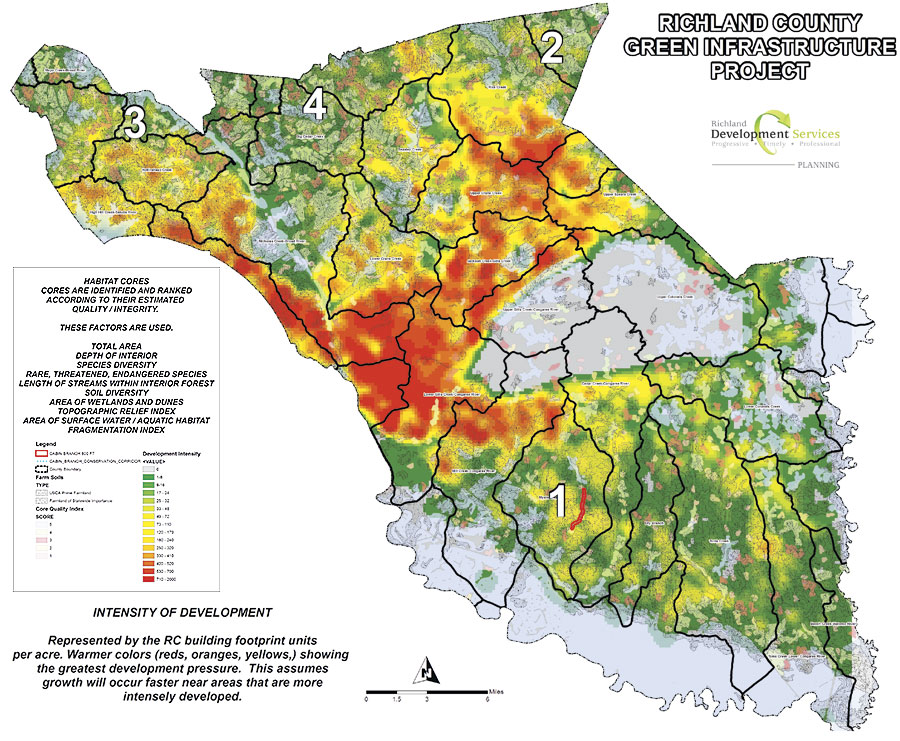

With the task force’s mission set, Carter executed GIS analyses to determine priority areas in Richland County. She referenced Firehock’s guide as a road map for gathering and analyzing data, as well as evaluating and prioritizing critical resources.

Once Carter had the essential data layers in place—including existing county GIS layers such as conservation easements, address points, and zoning—she used tools from Esri to create asset maps and maps of intact habitats, also referred to as cores. Carter employed ArcGIS Spatial Analyst for ArcGIS Desktop to conduct landscape analyses, assess fragmentation and risks, develop a core quality index, and prioritize opportunities.

“The first step to mapping the intact habitat cores is identifying the location and shape of habitat cores,” Carter said. “The second step is ranking the cores based on their ecological integrity using the best available data and science.”

The process took Carter approximately six months to complete.

“Brenda took the ball and ran with it,” Epps said. “The project would have been dropped if she hadn’t been interested, taken the reins, and done all the hard work.”

With the green infrastructure tool in place, Carter identified four priority areas in the county that comprise unique rural lands and waters. Each of these locations met the criteria of an intact core at risk of losing its natural assets. As part of the green infrastructure plan, Carter and Epps also identified potential projects to protect the cores—such as purchasing easements to preserve certain streams—and made clear the benefits of implementing them.

“I’ve been doing environmental work for 30 years,” Epps said. “I had a picture of what the green infrastructure model would look like and, in the end, it didn’t resemble what I had in mind. But that’s what [is] cool—Brenda used scientific data and tools to set the strategy. It’s not just about picking out what we think we should protect; it’s scientifically supported.”

Scientifically Preserving Natural Resources

The task force presented the green infrastructure plan and maps to the Richland County Conservation Commission, a group of 11 members appointed by the County Council to implement conservation goals. The commission was impressed.

“Science proved what they were thinking all along,” Carter said. “Now they have scientific evidence to prove which areas need protection and restoration.”

The team plans to present the information to the County Council as well, but progress has already begun on the policy side. Talks are taking place on how to resolve issues with zoning and the county’s comprehensive plan. And the county’s land administration department is starting to rewrite the land development code, keeping the priority cores top of mind.

“We’re not going to write code to keep developers from [building new homes],” said Carroll Williamson, land development administrator with Richland County. But the “new codes will guide smarter development that will be better for the land, people’s investments, and our county in the future. We used to tell developers that green infrastructure was a ‘nice to have’ feature. But if we can say scientifically that green infrastructure is critical to our well-being, then it takes on much greater significance.”

Moving forward, the team will continue the project and identify additional priority cores throughout the county’s council areas. They’re excited about the possibilities that the green infrastructure plan can bring to the county, including for the local economy. Helping people—especially county executives and developers—understand the benefits of green infrastructure will be critical.

“Green infrastructure is a big idea,” Epps said. “We want to conserve not just because we like trees. In the long term, green infrastructure provides a more sustainable and resilient community. So 20 years from now when we have another 1,000-year flood, a lot less people will be impacted.”

For Carter, green infrastructure means using her craft to enhance quality of life for all of Richland County, for years to come.

“We don’t want to re-create the flood situation that we had before,” Carter said. “We don’t want to damage the wetlands or cut down all our trees. We want to be able to have good water quality for the entire county. We want to preserve the natural resources that we have in the county so we can protect our quality of life. We want to grow, but we want to have smart growth.”

For more information about this green infrastructure implementation, email Brenda Carter, GISP. To learn more about how to start a green infrastructure plan in your community, visit Esri’s Green Infrastructure website.