When Vicky Kistler, Allentown, Pennsylvania’s director of health, and Matt Leibert, the city’s chief information officer, traveled together to an Esri conference in Philadelphia in 2003, they had big hopes for what GIS could provide for the city, imagining that one day they might have an advanced platform that could help them visualize and track the spread of disease in real time. Little did they know, a global pandemic 17 years later would give them the chance to adopt this capability.

Today, Allentown has taken the lead on a four-city, GIS-based community contact tracing initiative alongside Bethlehem, York City, and Wilkes-Barre that is poised to set the foundation for one of the United States’ more promising responses to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

The Limitations of an App-Based Model

When the pandemic first hit, many local governments turned to app-based solutions for contact tracing and exposure notification to try and keep up with the spread of the virus. Unfortunately, cities often found themselves in situations where this app-based model failed to garner momentum, resulting in adoption rates below those required to be effective. So state and local governments working to build up their contact tracing workforces relied, in large part, on traditional manual processes.

As the pandemic has dragged on, transmission has advanced to community spread, where those who get infected are unable to pinpoint how they contracted the virus. This makes identifying and tracking contacts much more difficult. In turn, it’s necessary to adopt a location-focused approach.

But the problem is far more complicated than downloading apps and building up the workforce, according to Matt Leger, policy research analyst for the Innovations in Government Program at Harvard Kennedy School, who also serves as director of strategy at CONTRACE Public Health Corps, a social enterprise that provides COVID-19 contact tracing workforce and advisory solutions to the public and private sectors. Tracing programs face significant operational constraints aggravated by often outdated back end IT infrastructure that slows responses, he said.

Combining person-to-person tracing with upgraded IT infrastructure and GIS tools, however, can help overcome these limitations.

Layers of Benefits to Using GIS

That is exactly the approach Allentown has taken. As Kistler and Leibert explained, using community contact tracing tools from Esri produces multiple layers of benefits.

In the first place, these tools gave Allentown a running start, since it was already using the ArcGIS platform. Allentown invested in IT solutions, including broadening its GIS capacity, several years ago—even in a period of resource scarcity—in hopes that the investment would increase productivity.

This foresight continues to produce benefits for both routine and extraordinary service demands. Although the GIS capacity differs among the four cities participating in the community contact tracing initiative, the fact that they all had access to ArcGIS tools provided the foundation for standardization and collaboration.

These tools also helped Allentown replace cumbersome, paper-based processes with digital technology and semiautomated workflows. Leibert and his team conducted a workflow analysis of the COVID-19 case investigation and contact tracing processes to identify duplicative actions. They quickly realized that the city needed far more advanced capabilities to be able to do contact tracing effectively.

Officials identified nine manual steps that had to be taken between receiving data from the National Electronic Disease Surveillance System (NEDSS) and sending the data back to the Pennsylvania Department of Health—a very labor-intensive effort filled with risks of human error. And this was just for case investigation; it did not include the steps needed for contact tracing.

Joseph Yashur, community health specialist for the City of Bethlehem, agreed that new capabilities were needed to be able to do successful contact tracing. He noted that tasks that previously took hours to complete, including performing quality assurance on the data, are done much more efficiently using Esri tools such as ArcGIS Survey123.

Myriad Advantages for the Community

For the four Pennsylvania cities participating in this initiative, the now automated and spatially oriented workflows that connect case investigation and contact tracing will produce substantial advantages as community contact tracing accelerates. Examples of the many manual steps that have been automated include verifying addresses and notifying contact tracing staff when there is a rapid reassignment of cases. This will significantly improve efficiency.

But as Joe McMahon, former managing director for Allentown’s mayor, Ray O’Connell, pointed out, “It’s not just a matter of efficiency; it’s a matter of accuracy.” And the original contact tracing platform provided to the City of Allentown by the state’s department of health was not equipped for the level of detail needed to do contact tracing at scale, which would have affected accuracy.

“You know the old saying—if you enter it once, it’s less likely that there will be transferred errors throughout multiple systems,” McMahon added.

Yet the spatial nature of contact tracing furthers the ability of city leaders to inform the public and enact strategic, place-based interventions. So accuracy is key.

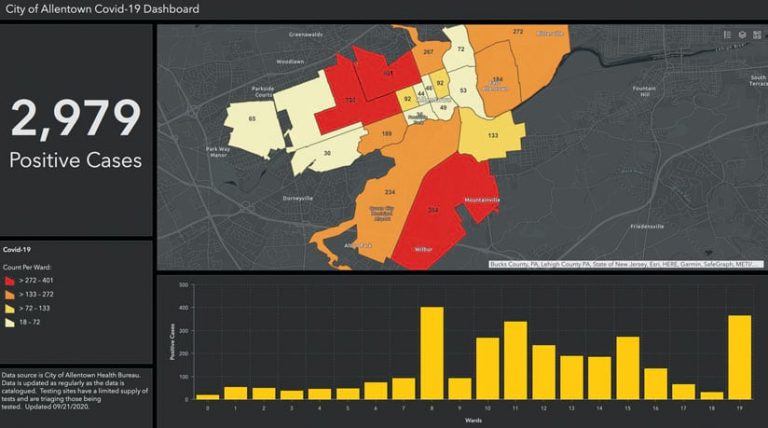

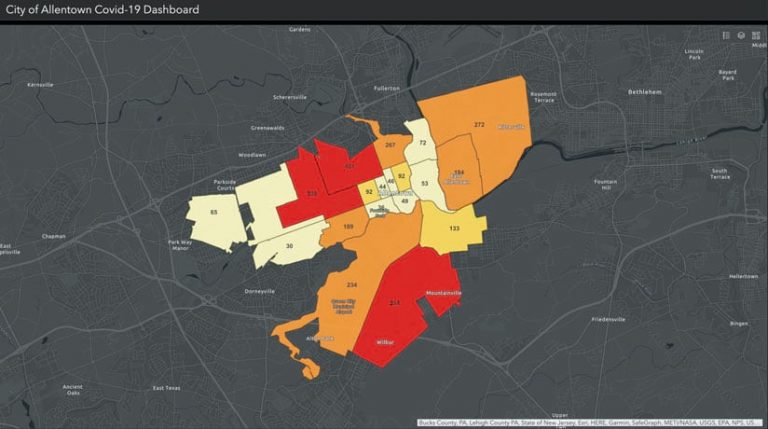

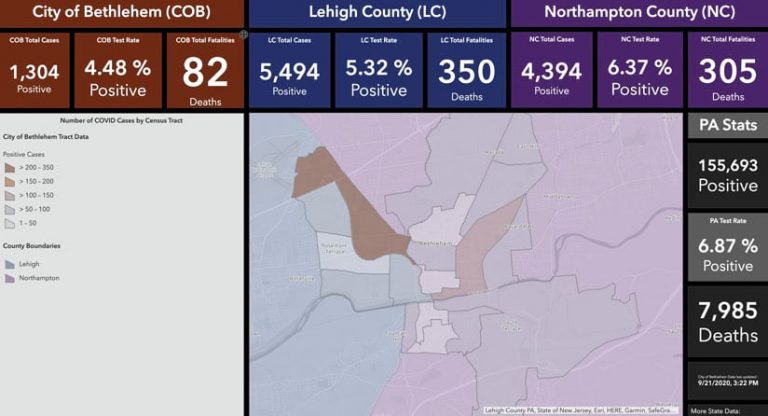

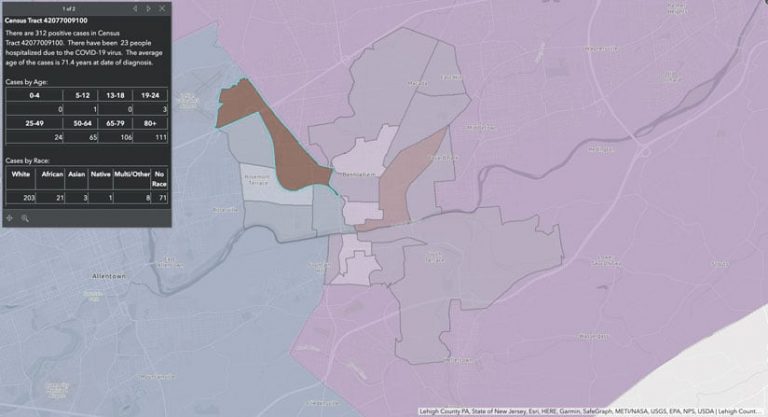

With the GIS-based contact tracing tools Allentown, Bethlehem, York City, and Wilkes-Barre have put in place, officials can protect people’s privacy while also providing dashboards and map narratives of COVID-19 cases in a fashion that clearly visualizes what is going on. This, in turn, helps improve community safety.

Geographic analysis can also assist by making connections among the locations of the disease, affected individuals, and nearby available resources. In fact, Allentown intends to integrate an automated notification system to help communicate information to high-risk neighborhoods and to people who have tested negative or been exposed to someone who has tested positive.

Looking Ahead to Future Public Health Uses

Another benefit of having a cloud-based platform is the opportunity to share innovations and discoveries with other public health departments. As Kistler emphasized, she hopes that, as the other cities in her collaborative join in using the technology, “they may have ideas we haven’t thought of that could enhance our capabilities even further.”

“We’re all borrowing from one another. It’s information sharing that we’re looking at doing,” said Kristen Wenrich, Bethlehem’s director of health. And that’s something she takes pride in. “I’m anticipating that we’ll hold regular meetings, since we’re all speaking in the same language of GIS,” she added.

In addition, having a GIS-based foundation allows multiple agencies to gain even broader insight into public health. Both Bethlehem and Allentown public health leaders hope that the layered data will help cities pay more attention to the social determinants of health and how neighborhoods are affected by a multitude of factors. Officials are currently considering how to apply GIS technology to trace sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), tuberculosis, whooping cough, and other illnesses. And the four cities in the collaborative are optimistic that, by crossing health data with geographic data, they can join together to apply for research grants and respond to the causes of health disparities.

According to Wenrich, Bethlehem plans to have officials—when they become more comfortable with the power of spatial analysis—use these new capabilities for other disease prevention activities.

“When you see mapped clusters, you can also see potential action that can be taken,” she said.

For example, these capabilities helped Bethlehem improve outreach efforts to Spanish-speaking communities after the public health department saw the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 in certain Hispanic neighborhoods. Now, Wenrich is contemplating applying this technology more broadly—for food inspections, public health nuisance complaints, STDs, and highway safety initiatives, for example.

The officials also hope that the increased efficiencies they’ve experienced will allow the state’s public health department to make better decisions about other important tasks, such as mass flu shot and COVID-19 vaccine distribution, when the latter becomes available.

Often, according to McMahon, the public doesn’t understand the need for technology investments. But, he said, “the transition to this platform [is] an investment that will have massive returns for not just public health but [also] city government overall.”