Online Exclusive

In the summer of 1854, the Soho neighborhood in the city of London, England, was gripped by a cholera outbreak that was killing an increasing number of Londoners each day. By the end of the outbreak, 616 people had died. However, this number could have been much higher if it were not for the insight and actions of Dr. John Snow, who utilized spatial analysis with a simple map to determine that a single water pump was the source of the outbreak. Snow eventually became known as the “father” of modern-day epidemiology, and the world was introduced to the power of spatial analysis. While this was a watershed moment in many ways, we have to wonder how this outbreak would be different if it were to occur today. One thing for certain is that web-based mapping and social media would play a significant role in helping minimize the impacts of this crisis.

How?

That question was answered in the fall of 2012 in the Department of Geography at the University of Oregon in a course called Our Digital Earth, and ArcGIS Online was the core resource that made it all possible.

Our Digital Earth is a new freshman course that was awarded Esri’s ArcGIS Online for Educators grant for developing a course that uses ArcGIS Online in a way that facilitates an introduction to the world of geospatial data and technology for non-GIS students. Over the course of 10 weeks, students received the following message:

Every day of your life, you make several decisions that are based on geography. Using your smartphone, you inquire where is the best place to have lunch with friends and how is the best way to get to the restaurant. On your laptop, you roam the earth to see where your relatives live and observe photos of those locations that others have taken. You receive texts from people you don’t know who are explaining where a social event is happening tonight. Every day of your life, you are interacting with geospatial data and technologies but are perhaps unaware of how important they are in our world.

Unlike typical GIS classes that are offered as upper-division courses to students with some formal geography or computational training, the goal of Our Digital Earth is to invite students across all disciplines to examine how geospatial data is collected and used, how geospatial technologies have transformed the way we think and make decisions, and the important societal issues that result. ArcGIS Online provides us with an opportunity to have a broad range of students learn how to develop web-based mapping applications by integrating satellite imagery with their own data they collected in the field or from the web. The mapping applications are created as part of a set of assignments that include everything from mapping students’ routes to campus with spatial features and social media to creating web-based applications that shed light on socioeconomic inequalities in major cities. Of these assignments, the one that students were most excited with this term was learning how to engage in a crowdsourcing activity to respond to disasters, such as a cholera outbreak.

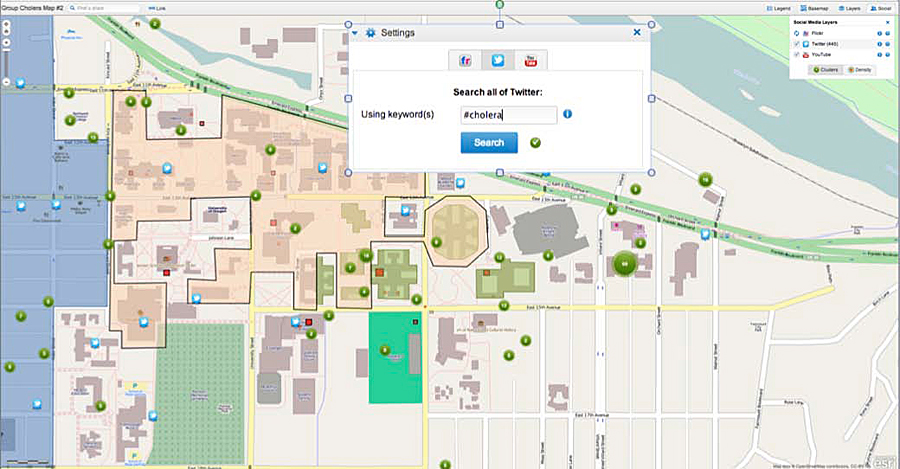

Over two weeks in November, our class set out to simulate a modern-day version of the 1854 Soho cholera outbreak on the campus of the University of Oregon. However, instead of sketching out cholera deaths on a paper map, students utilized e-mail alerts, posts on a dedicated Facebook page, and Twitter messages that collectively provided information on the types of individuals who were infected each day; their daily activity patterns, including walking paths and courses in which they were enrolled; the locations of water sources around campus; and the status of water testing at potentially infected sites. In small groups, students were responsible for assigning individual tasks among themselves to efficiently map out the diverse range of information that they received on a daily basis. Students created maps in ArcGIS Online, shared the maps among group members, collectively mapped out the cholera-related information, and performed a visualization of all the data to determine where the cholera outbreak originated.

Most impressive in this assignment was that students could easily map Tweets by utilizing one of the ArcGIS Online social media mapping applications. Students simply entered in keywords, and the Tweets posted by the teaching staff were placed on the map in the location from where the Tweet was posted. For example, if I were to Tweet from outside a residence on campus that I had been infected with cholera, a student could search the keyword cholera and a feature would be placed in the location from where I posted the message. The response from this assignment was unanimously enthusiastic, and ArcGIS Online made it all possible.

As someone who teaches multiple GIS-related courses, I was impressed at how students from all disciplines (e.g., geography, music, psychology, journalism) could easily create not just maps but web-based mapping applications. One example was a mapping application that demonstrated the potential presence of food deserts in Portland, Oregon. Students with little to no GIS experience were able to create an application in which three separate maps representing socioeconomic data and grocery store locations zoom and pan in unison, which were accompanied by text describing the relationship between quality of life and access to major grocery stores.

From an administrative perspective, ArcGIS Online provided a means for students to store data and projects without having them rely on desktop software in a lab. That means that students can access their work from anywhere in the world! Also, having students be able to share their projects with the public provided an added sense of pride in their work and was extremely helpful in advertising the course to the university community and beyond.

As Our Digital Earth wraps up this term, we are very excited about future offerings of this course and the role in which ArcGIS Online will help it grow into an integral part of the geography curriculum. Without a doubt, we have already engaged a new group of GIS professionals that would have likely not discovered this discipline through traditional means. Dr. John Snow would surely be impressed!

About the Author

Christopher Bone, assistant professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Oregon, received his PhD from Simon Fraser University in Canada. His work is focused on modeling coupled human-natural systems, with specific attention paid to large-scale forest disturbances.