Year One of a Bold Partnership That the World Needs

Esri president and cofounder Jack Dangermond and Autodesk CEO Andrew Anagnost both agreed to provide insights on the Esri-Autodesk partnership, now entering its second year. They discussed the specific fruits of the collaboration to date, but they focused on the motivation and impetus for this historic handshake.

If you’ve ever had to work with one foot in each of the worlds of CAD/CAE (computer aided drafting/design and computer aided engineering) and GIS, you know this partnership is a very, very big deal.

You cannot design in a vacuum.

You cannot build in a vacuum.

You cannot operate and manage infrastructure and assets in a vacuum.

The world—the built environment we inhabit—is growing so rapidly that legacy methods and resources serving architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) simply will not be able to meet demands. It has always been true that you cannot design/build/operate/manage in a vacuum, but in the present day—and every day moving forward—those burdens will increase. But so will the opportunities.

GIS and CAD, CAD and GIS: there is no way to disconnect the two as essential in growing and managing the built environment. During the decades when both grew to be the essential tools we use today, they were somewhat disconnected. Many of us have had to learn two systems and work with two departments within two sets of disciplines that have at times (to be frank) seemed adversarial.

Despite the apparent disconnect, over the years there have been many key areas of collaboration between the two global leaders for GIS and CAD/CAE. Remember ArcCAD?

What’s so different this time? How might this partnership solve persistent problems? It might seem like we are sensationalizing it by saying that a kind of “cold war” is over, but that’s part of the story.

The key takeaway we see is that this partnership may be a harbinger of a change in mind-set and a reaction to an imperative for change.

Anywhere, Anytime

The most recent collaboration between these two geospatial giants began about three years ago under then-Autodesk CEO Carl Bass (details are in the Who Asked Whom? section). Since Bass’s departure in 2017, Anagnost as CEO has overseen the partnership on the Autodesk side. Anagnost is an engineer in aeronautics and manufacturing with a doctorate from Stanford. He has had many roles at Autodesk in his nearly two decades with the company, most notably shepherding the development of Autodesk Inventor.

Like Jack Dangermond, Anagnost exhibits seemingly boundless energy and passion for his company and the future. Behind his stand-up desk in his sensible and efficient office at the company headquarters in San Francisco, he has a poster diagramming the flight paths of all spacecraft and probe missions throughout the solar system and beyond. Among his other passions is the commercialization of space.

The interview ranged all over the place, but in a good way: automation, licensing, the cloud, challenges and opportunities for surveyors, and more. The focus of the following conversation was the partnership.

Gavin Schrock (GS): The partnership had been germinating for a while. What was your reaction when you first heard about it?

Andrew Anagnost (AA): My reaction was: it’s about time. This is the kind of partnership that needs to happen. You know when we [Anagnost and Dangermond] talked about it on the main stage [at Autodesk University 2017], we talked about this as our vision to be able to make anything anywhere: a little tag line we put on it.

It is super important; it is super exciting. If you look big-picture-wise where things are going, people are trying to manage and evolve the design of urban environments and infrastructure in more sustainable, reliable ways, where they can build a lot more things under the same kind of budget and constraints they have today.

We know we are all living in a world right now where there is not enough funding, resources, or capability to build all of the infrastructure: that which needs to be rebuilt in the mature world and all of the infrastructure and cities that need to be built in the maturing world.

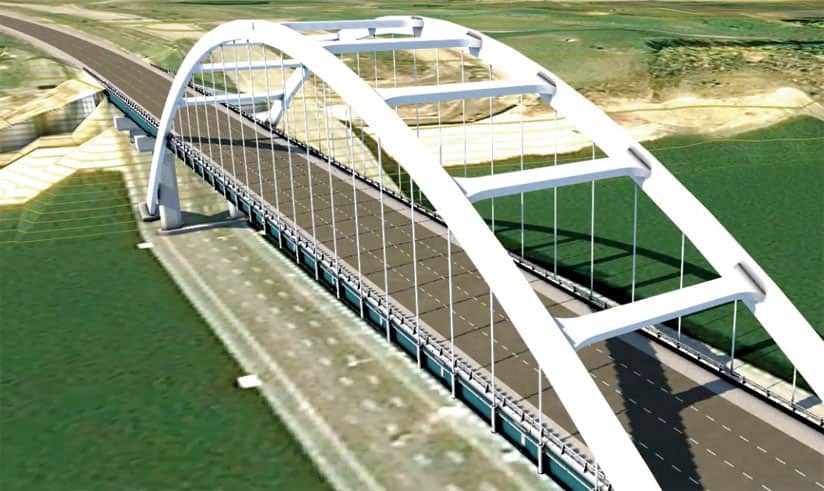

At Autodesk we see this as a fundamental capacity problem. City planners, and people trying to build a city or an infrastructure project that connects a city, they want to visualize the whole thing in context. They want to see the as-planned, the as-designed, and as-built state in a dynamic, intelligent, useful, and persistent city model.

Esri owns the planning, city-facing context view of what the whole city looks like and the associated data at that scale, and we own the content that shows up inside the models: the buildings, the roads—all of these things.

We need the information from that system to create the correct context for the things we’re designing inside of Autodesk’s InfraWorks, inside of Civil 3D, inside of Revit—all sorts of applications. And they need the actual as-built or as-designed entities to sit intelligently inside their view of the world. We should be seamlessly sharing this information back and forth in such a way that most people never notice that it is from shared applications.

Esri and Autodesk were once considered competitors, but that didn’t make any sense at all because our core competencies were in completely different areas.

Both companies are strongly committed to supporting these needs and contributing, in concert, respective essential pieces of the whole. This is something the world needs right now for better planning, for better resourcing, for better understanding of what needs to be built and when.

Differences that Unite in Purpose

What distinguishes the different core competencies of the two companies is not as simple as the difference between CAD and GIS (if viewed simply as software), but those structural differences drove some of what would later become discipline-level divisions. To understand the impetus behind this partnership, we also must understand those differences and how the recognition of strengths of the other fostered collaboration.

The best explanation I know contrasting CAD/CAE and GIS is from Jack Dangermond in our recent interview at his office in the Esri headquarters in Redlands, California. Dangermond, who cofounded, with his wife Laura Dangermond, Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. (Esri), in 1969, did not originally intend it to be a software startup. His background and education were in landscape architecture.

During the course of Dangermond’s studies, an amazing opportunity changed his plans: to study and work in the Harvard labs on the emerging fields of computer graphics, spatial analysis, and quantitative geography. After Dangermond founded Esri postgraduation, the company was at first a provider of services on a project basis, but later, so many people, governments, and companies recognized the power of what Dangermond and his team could do that they pressed him to make his software a supported product.

During our recent interview, Dangermond outlined that history, as well as the evolution of both Esri and GIS in general.

GS: How would you describe the differences between CAD and GIS?

Jack Dangermond (JD): Let’s start with the core technology. In 1985 I wrote an article, “CAD vs. GIS for Mapping.” CAD is just a fabulous technology, Autodesk’s AutoCAD being the leader, but its architecture is a data model which manages and displays graphics. You store in a display list, in a file, all the little graphic elements.

In GIS you store geographic features rather than graphic features. You would display the geographic features—points, lines, and polygons—by generating them from a database and associating the geographic features on the fly. [That] was so much slower in the 1980s.

But the distinction [with GIS] was that you could do analytics on these simple georelational tables: polygon overlay, buffer zones, and hundreds of others, whereas you couldn’t do those analytics on a graphics-only file. Also [in GIS] you could make multiple views of the data model all from a single database.

It was [a] fundamental difference in the technology—at that time. The advantage of CAD was that it had lightning speed, and still does, of course, in graphics display. So, the engineers used it as a graphic engine. People would build add-ons to add a little geoprocessing to the CAD files, but the core differences in technology remained.

[For a period of time] Autodesk was very ambitious about the idea of getting into the geoprocessing world, so they bought a series of companies and tried to extend the AutoCAD technology in the GIS space. I think the evidence is that this did not work out. I think they were very right in doing it, but their main core business has been in the workflows of engineering design, architectural design, civil engineering, and surveyors.

GS: There seemed to be two distinct communities—will it always be that way?

JD: A lot of it has to do with just not having enough capacity to learn multiple sets of tools and not having the capacity to be both an engineer and planner at the same time, and so then little weird things begin emerging: them versus us.

If we are really talking about successful urban management and making cities more livable, operating more affectively, making better investments in infrastructure, we need the opposite—we need to try to break down barriers between professionals so they can easily and seamlessly use each other’s data.

Who Asked Whom?

When we write about partnerships in the geospatial industry, we always try to find out “who asked whom to the dance.” We spoke with Chris Andrews, senior product manager in Esri’s 3D product management group: a major player in bringing the two together and widely recognized as the author of this partnership.

GS: You had worked at a number of GIS firms, then worked at Autodesk, and now at Esri. Was having experience in both worlds a major influence in your initiative to foster a partnership?

Chris Andrews (CA): When I joined Autodesk in 2007, because of my familiarity with the GIS market business partner programs and tech, I was tasked with advising partners and development teams at Autodesk in how to be competitive in the GIS space. I moved into the role as technical product manager on the digital cities effort there and was involved from scratch in Infrastructure Modeler (now InfraWorks), originally built as a competitive city planning-based concept application to go into the market against other GIS solutions.

I left Autodesk after being there about seven years and ended up at Esri. I was approached by one of my [former Autodesk] colleagues and asked if we should start up a conversation about bringing together Esri and Autodesk, both knowing how compatible our marketing strategies had become. But I said we should hold off awhile as I was new.

About a year of my time focused on the ArcGIS Earth effort, which was really important for not only our defense and intelligence community customers, but our beta user stats revealed that 40 percent of those users self-identified as being from AEC disciplines. That was a pretty big surprise to a lot of folks: more indication that working with Autodesk in the AEC arena would be a good idea.

Then I reached out to a VP at Autodesk, my former boss, and was connected to Theo Agelopoulos [director, infrastructure business strategy, and marketing]. We traded emails. I went up and visited San Francisco [Autodesk’s headquarters], put together a slide deck, talked to Jack [Dangermond] and some directors, and tried to manage expectations.

Theo and others continued friendly conversations, and that fall Carl Bass [then Autodesk CEO] came to visit Jack [Dangermond] in Redlands. A real career highlight was to be part of that meeting with them for four to five hours.

Fascinating to me was: the things I thought they would focus on were different from the topics that they actually spent the most time on. They did follow the thread of the planned discussion, but, considering the history, I thought the conversation around potential Civil 3D integration with ArcGIS would be really hard. I think they jumped through that in five minutes.

As the meeting progressed, it was clear that we both wanted to provide frameworks and platforms so that our users could both benefit from an improved experience that could bring the value of location awareness into the engineering workflow and engineering data back into asset life cycle management processes.

A Year of Progress

Initial collaborations mostly build off the same kinds of tools available to the respective developer communities for each company—open APIs (application programming interfaces)—but each with some direct guidance from development counterparts of the other.

Agelopoulos said that both companies did not want to simply say that it is a great partnership without substance. They wanted to deliver beneficial outcomes for the shared user experience in the first year. The most logical first step for Autodesk was to enable InfraWorks to read data from Esri sources. The result is the recently released Autodesk Connector for ArcGIS.

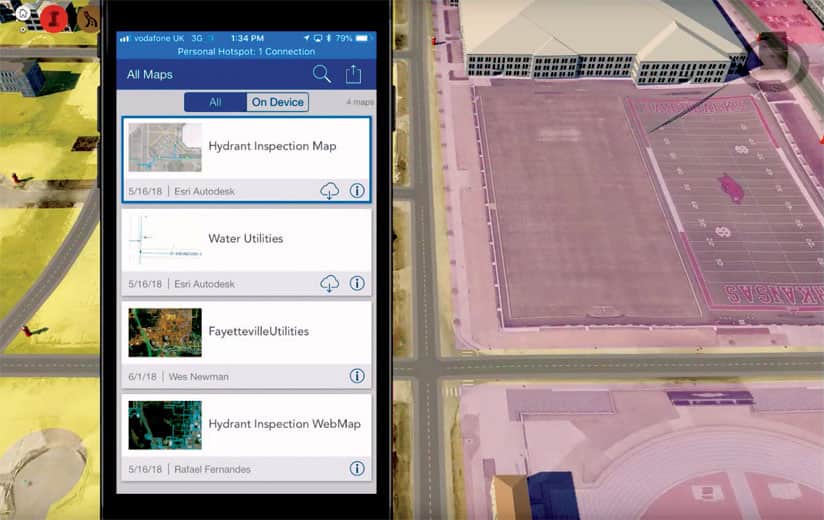

At the 2018 Esri User Conference, Wes Newman, senior technical marketing manager at Autodesk, took us for a test-drive.

“Bring up a map, and this creates an area of interest from your current project extents,” said Newman. “A familiar look and feel for an ArcGIS user. We select by features we would see in web maps, so both will show as componentized toolsets within Autodesk.

“Select the data types we want. For instance, we can select water utilities, a feature service with a bunch of feature services underneath; select valves and tell them they’ll be like pipeline connectors; select laterals and mains and tell them those will be pipelines. And then they are live connected [not an import per se].”

When I asked about updates, Newman pulled out his phone, opened Collector for ArcGIS (the popular field asset mapping app), and added a new survey monument to the corresponding feature in ArcGIS in the cloud. And that, in turn, showed up in the InfraWorks instance.

Initially, key developments from the partnership for the Esri community revolve around the ability to integrate Autodesk Revit models. The data-rich Revit BIM (building information models) will be able to feed essential interior elements to the soon-to-be-released ArcGIS Indoors mapping system and will be useful for fleshing out corresponding buildings in ArcGIS Urban, also forthcoming.

Services and Scenes

The ability to manage, almost without limitation, the data and models for an entire city, down to the interior of each building, is something that legacy CAD could not do and certainly that legacy GIS could not. But the way geospatial data is now handled, more as services, has revolutionized that in GIS. We are no longer hobbled by having to do full translations of data with different tools for every data type and source. We asked Jack Dangermond to explain.

JD: Part of the reason why this relationship is comparatively and relatively easy to implement is because we have moved from client-server to an everything-as-services-in-the-cloud platform.

Modern GIS today is all services based; every client talks to the database through services. So if I’m on a desktop, I’m in ArcGIS Pro, I’m talking to an ArcGIS server through a services connection and a REST (representational state transfer) endpoint. I find it, connect to it; I’m never really dealing with the record change, I’m dealing with a view of the record change. And that means different clients can operate through REST endpoints, and those are open APIs. We can have distributed servers that are interconnected, and my clients can talk to those distributed services.

If I have imagery, my clients and apps talk to the images by way of something called a web map, or a web scene that is a 3D technical specification, or a web layer which is like shapefiles of the old days. We’ve taken hundreds of individual formats that live all over the Internet and can now connect to big data, or real-time data, many types of 3D data, vector data, unstructured data—but we always talk to them through a service.

In IT parlance, this is a miracle. There was a phase during the 1990s where enterprise service buses were created, and there was a whole bunch of them. With the advent of web services and REST, all that went away.

The ArcGIS portal creates a common language by abstracting multiple geospatial datasets into common view. That means the clients can talk to this distributed geospatial environment through a common set of specifications. And it is completely open. This common language of any kind of geospatial data allows an individual to create a web map and then view it and share it with a community.

To create smart cities, it turns out that you need a scene, or what we call a multipatch. A scene is a 3D dataset; we invented this about 15 years ago, and it turns out that [a] 3D smart multipatch dataset really scales well, so I can fly around like you [do] in a Google-like environment, which is a different type of model, but you also have a smart feature database with millions and millions of features.

Warp Speed

I had heard Autodesk referred to by some as the “Starship Autodesk,” and now, with Anagnost at the helm, there does appear to be a new mood afoot there, this new partnership as evidence of that. I asked Anagnost about the changes in the culture of Autodesk he has observed in his years there.

AA: Over the last couple of years we moved to a world where 60 percent of the employees have been here less than five years. The company is 9,000 people now; you can’t grow that fast without having a whole new infusion of talent and capability, and this is absolutely evolving the culture.

But there’s a few things that will never change. The thing that attracts people to Autodesk and keeps people at Autodesk is the cool amazing work our customers do. Our people see the impacts of their work in their daily lives—bridges, buildings, entertainment, [and more].

This passion for impact hasn’t changed at Autodesk. The new generation we are bringing in— they are just as passionate about those impacts as the previous generation.

GS: What would you like to see next from this partnership?

AA: I would like to see us creating a seamless opportunity in the cloud for our shared data—customers to have digital representations of the planning state, the in-process state, and the as-built state and be able to feed that information back into the next design. To have a closed loop, they are pulling data, using it, moderating it, and getting it from a central place where our respective technologies are feeding that location. And it’s two-way: you can push info in and pull it out, you can take info from the current state to the digital representation and use it to inform the next revision of what you are trying to do.

The Imperative

Staff from xyHt presented each of these two leaders token gifts from the days of geospatial past—long before anything was called geospatial. Jack Dangermond, who has often spoken of his appreciation of surveyors and surveying, received an 1870 Gurley surveyor’s transit. To Andrew Anagnost xyHt presented a 1936 K&E catalog featuring beautifully drawn figures of the drafting supplies of that era.

That instrument and the supplies in the catalog represent the state of the art in those eras. But those would be nearly impractical to try to use in today’s accelerated world. Change and modernization are imperative.

The gifts emphasize how accelerated our world has become by necessity. Since the publication of that catalog in 1936, the population of the world has more than tripled, and since 1870, the year of the manufacture of that transit, the world’s population has more than quadrupled. Progress in AEC, geomatics, and geospatial tools and solutions has mostly kept up. But it will get tougher, especially if we continue with legacy compartmentalized design/build/operate/manage processes.

This partnership is significant on many levels; there were multiple imperatives for it to happen.