Andrea Wulf’s book The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World was on Esri president Jack Dangermond’s mind when he opened the 2016 Geodesign Summit.

Holding up a copy, Dangermond praised Wulf’s biography of Humboldt, a German naturalist and geographer whom the author has called “nature’s prophet” and whose geographic explorations and scientific observations 200 years ago still impact how people think about nature today: as a complex, inter-connected system.

Designing with Nature in Mind

If Humboldt were alive today, he may well have been at the forefront of geodesign, which supports designing with nature in mind and promotes a harmonious ecosystem.

Geodesign combines geographic science and GIS technology with design methodologies to produce data-driven solutions or plans that support healthier, smarter, and more sustainable communities.

At the summit, which was held January 27–28 at Esri headquarters in Redlands, California, Dangermond set the context for the 300 attendees, outlining some issues society faces on a global scale.

“You and I are living in a world that’s changing rapidly,” he said. “We are challenged [by] our population growth. And the footprint of that and its impact—on nature, on climate change, and on just about everything—is enormous.”

He called on audience members to learn geodesign methodologies and supporting technologies to make positive changes.

“It’s why we are so passionate about trying to create a better future, considering science and our best design and technology,” Dangermond said. “The world needs you, and the world needs you to be inspired to grasp this whole set of methodologies and tools to work desperately to alter the course of what’s going on. Because the arrows are going in the wrong direction by any measure. The challenge for geodesigners is to turn those arrows around.”

One of the Greatest Geodesigners

One geodesigner who is making strides in the right direction is Spanish landscape architect, urban planner, and architect Arancha Muñoz-Criado. In introducing her to the audience, Dangermond described her as “one of the greatest geodesigners I’ve ever met.”

Muñoz-Criado has devoted much of her career to introducing land conservation and green infrastructure into the planning process in the Valencia region of Spain, where she grew up.

She loves the land—especially the bucolic fishing village on the Mediterranean Sea just south of Valencia where, as a child, she spent weekends and holidays. The people living there were poor, eking out their livelihoods by fishing. But their surroundings were rich and bursting with nature.

“I grew up in a beautiful area in Spain with pristine beaches, mountains [overlooking] the seas, and wonderful terraces full of almond trees and vineyards,” Muñoz-Criado said.

But in the 1960s and 1970s, tourists from other parts of Europe discovered the fishing village and its beaches. Soon, a crop of summer houses replaced many of the almond trees.

“Suddenly [the village] grew very, very rapidly,” said Muñoz-Criado. “It brought a lot of money and resources for the local people, so everybody was happy. But development was allowed anywhere, and that was a total disaster.”

Growing Well While Preserving Place

Seeing what happened in her beloved fishing village influenced Muñoz-Criado in her choice of career.

“I thought there was another way of growing: we could grow but grow well, preserving the character and preserving the landscape of the place,” she said.

After earning a degree in architecture in Spain, where she was also trained as an urban planner, Muñoz-Criado worked briefly for renowned Finnish architect Aarno Ruusuvuori. Sensing her interest in landscape design, he encouraged her to study landscape architecture in the United States.

Muñoz-Criado was accepted to Harvard University, where she earned her master of landscape architecture degree in the early 1990s. She was a student of professor Carl Steinitz, the author of A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design.

While visiting friends in Boston, Muñoz-Criado would go to the Emerald Necklace, a seven-mile-long stretch of parks and waterways designed in the 1870s by American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. Muñoz-Criado said the concept of green infrastructure can be traced back to him.

“Every time I went there, I said, ‘What a simple idea,'” Muñoz-Criado remembered. “Find out which places…you [want] to preserve before growing, and then develop around these places.”

Greening Infrastructure

She brought those ideas home to Spain but realized that to achieve policy changes, she would have to work for the government to help enact them.

She spent five years working for the government of the autonomous region of Valencia, advocating landscape conservation and green infrastructure requirements in the planning process. Moving up the ranks, she eventually became regional secretary of territorial, urban planning, landscape and environment, where she was able to get the green infrastructure requirements put in place, thanks in part to the European Landscape Convention. The convention, adopted by the Council of Europe, seeks to create sustainable development based on balancing social, economic development, and environmental needs.

Muñoz-Criado also helped to get a European Union Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for the autonomous region of Valencia. The SEA requires by law that the region of Valencia consider sustainability when reviewing development projects.

Today, the 550 municipalities in the region must use geodesign in the planning process and take green infrastructure and land conservation into account when doing urban planning. And the regional government must approve those plans.

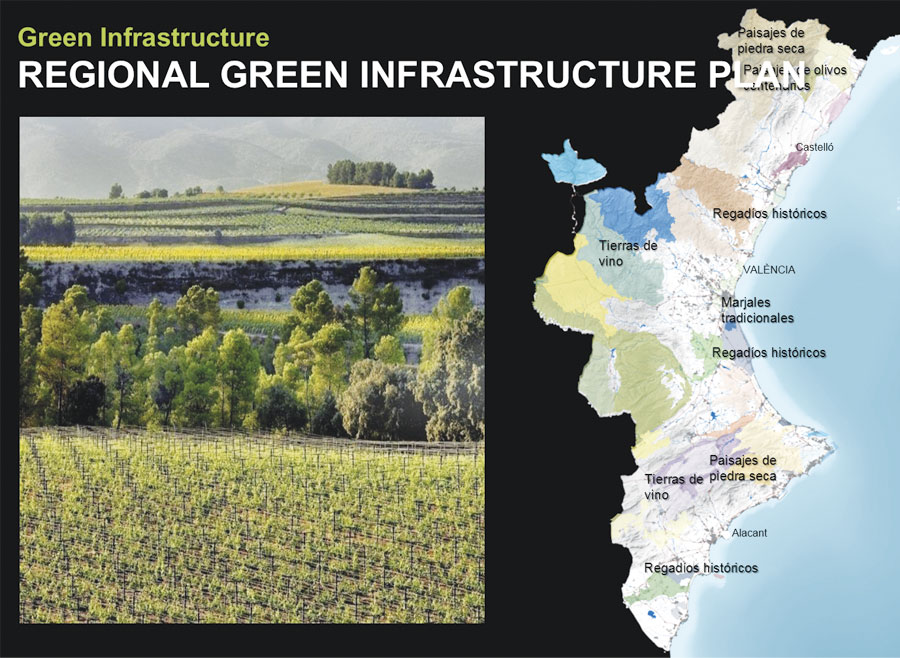

In the Valencia region, urban planning at both the regional and municipal scales incorporates green infrastructure. Working with others in regional government, Muñoz-Criado designed a regional green infrastructure map and a GIS application. Ecological, cultural, agricultural, and flood areas are shown on the map.

“Municipal planners, investors, and [other stakeholders]know that in the green areas, they have some environmental restrictions,” she said. “And they just have to click on the GIS map to know where [the restrictions] are.”

Today, a plan is in place to create a green infrastructure network in the Valencia region that promotes air quality and biodiversity. Rules set at a regional scale protect forests, wetlands, and agricultural areas. Huertas, or family gardens, are encouraged. In these gardens, landowners grow vegetables, such as tomatoes and onions, and then sell them at local farmers’ markets. Land is being set aside for bike paths, pedestrian walkways, urban gardens, green spaces, and urban parks. Views considered scenic or historic are protected too.

“If you have a beautiful mountain, you should not build anything that blocks the views of that mountain,” Muñoz-Criado said. “That mountain is part of the identity of that place and makes that place different from other places.”

Muñoz-Criado strongly believes that creating green infrastructure doesn’t run counter to economic development but, rather, enhances it.

“Many cities have destroyed prime agricultural lands, but those lands can be the [food] markets for our cities,” she said.

Protecting prime agricultural land provides an economic boost for local farmers and saves energy and money by reducing the need for having food shipped from distant places. More people in cities can then buy locally grown fruits and vegetables. And tourism is stimulated by protecting views of scenic areas such as mountains and historic sites like castles. Recreation opportunities increase when hiking trails are built in green corridors.

“Everyone has different sensitivities, but I have always been very emotional about the landscape,” said Muñoz-Criado, whose home in the fishing village was only five meters from the sea. “I love being in beautiful landscapes. I have appreciated them since I was a child.”