Despite the tendency of geogeeks to bury themselves in their work, professional collaboration (contact with other humans) is essential to identifying the broad spectrum of challenges facing GIS professionals, as well as the range of viable solutions. This is something we all learn sooner or later in our careers. We must crawl out from behind our monitors and interact with other professionals. This is helpful not only in finding solutions to our challenges but also in making sure we have identified these challenges in a broad and comprehensive manner. Otherwise, our solutions are too short-lived.

Idaho

Idaho is largely rural in nature. Boise and its environs are rapidly urbanizing, but there remains a significant amount of farmland, open range, and natural lands surrounding the urban area. Outside this island of urbanity, Idaho’s character is rural as far as the eye can see. Small towns dot the landscape, and larger cities (translation: population 50,000) are few and far between. Still, most of the counties in Idaho use GIS as part of their daily operations and employ one or more GIS professionals to staff their operations. As a result, GIS cohorts are scattered hither and yon with little or no daily contact outside of e-mail and phone calls.

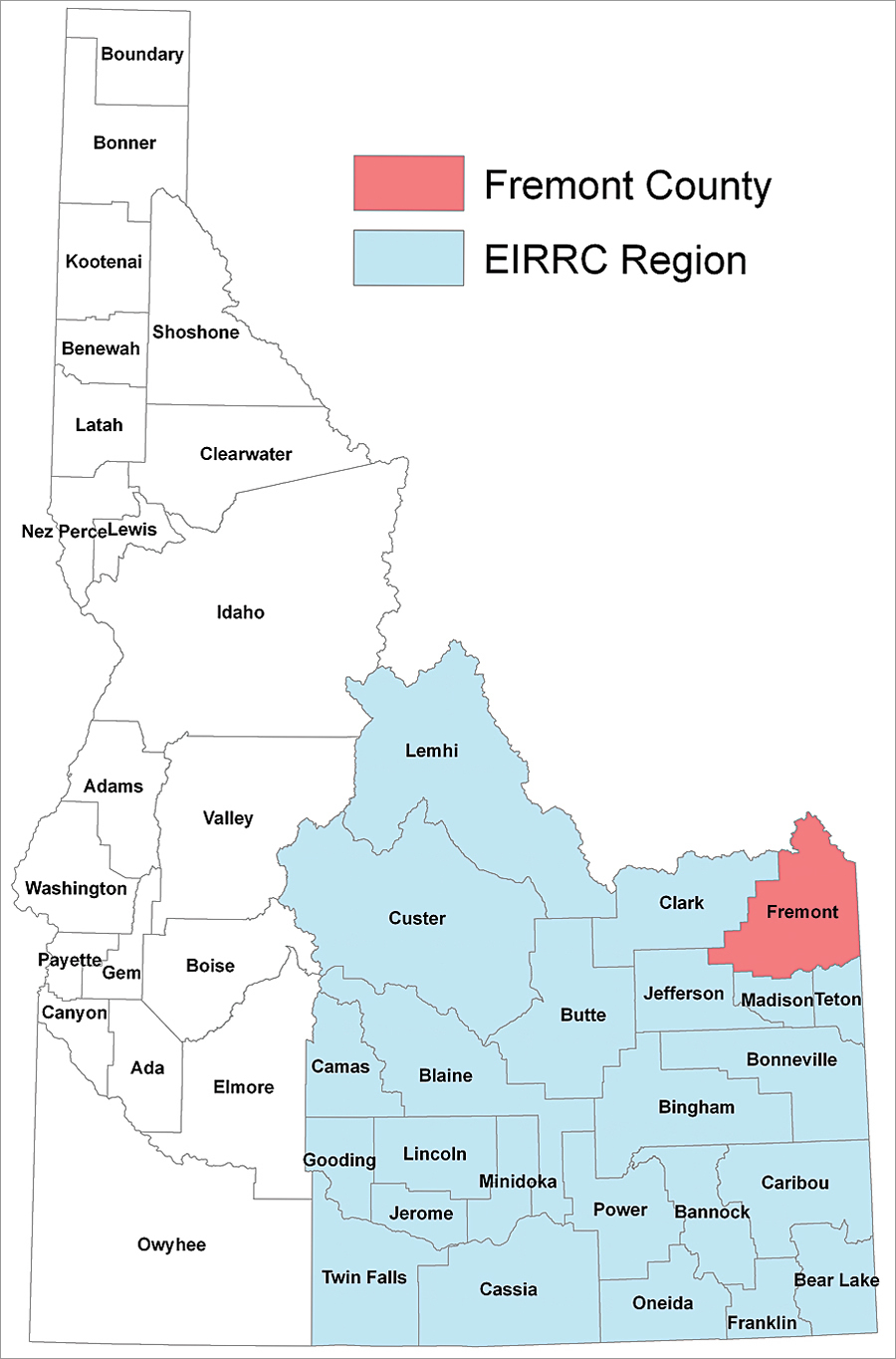

Idaho’s GIS activities have been robust for some time now, yet in the last few years significant efforts have been undertaken to provide better coordination between state agencies, counties, and cities. Idaho now has a geospatial information officer and a geospatial office for coordinating statewide GIS activity. This is helpful when dealing directly with the state, as access to resources and personnel is easier to find. With regard to regional collaboration, the state expanded its efforts by bringing in the consulting firm Croswell-Schulte. This resulted in Idaho being divided into three geographic areas represented by a Regional Resource Center to assist local GIS professionals to collaborate on issues of regional and statewide importance. In 2010, two regions adopted a business plan providing organization, structure, and guidance for improving GIS coordination and collaboration between cities, counties, the private sector, and others.

EIRRC

Moving to Idaho in 2011, I was surprised to find an active regional GIS group in the form of the Eastern Idaho Regional Resource Center (EIRRC). This group consists of GIS managers, analysts, private-sector GIS users, university staff, and survey professionals who meet on a monthly basis to discuss challenges facing the region. The group also coordinates with statewide officials, agencies, and councils. Its business plan says the following:

“Regional Resource Centers (RRCs) are organizational components of The Idaho Map (TIM), Idaho’s statewide GIS program. RRCs have the primary mission of supporting and coordinating GIS activities and users in specific geographic regions of the state, in coordination with the Idaho Geospatial Council (IGC) and the Idaho Geospatial Office (IGO).”

EIRRC is refreshingly active, with a full agenda of topics and undertakings that affect all the local participants. The group has active leadership and members who serve on both regional and statewide subcommittees. The group faces many challenges. Perhaps the biggest challenge is how to standardize a spatial data infrastructure that works for everyone. This challenge is being tackled both from the top down in the form of statewide leadership and from the bottom up in the form of regional collaboration and problem solving. As a rural state, Next Generation 911 is a critical opportunity to provide better geolocation from cell service. And more basic challenges, such as improving road centerline data or standardization of parcel data, remain a perennial focus.

Fremont County

I represent Fremont County, which covers more than 1,800 square miles with a year-round population of just over 13,000. It doesn’t get more rural than that. However, it is one of the gateways into Yellowstone National Park, and a large part of the county consists of the Caribou-Targhee National Forest. Fremont County is the most popular fly-fishing location for all Idaho and maintains one of the best snowmobile trail networks in the West. The southern portion of the county is rangeland and farmland with significant harvests of potatoes and barley. Fremont County is very active and faces many challenges, especially at the peak of summer tourist and harvest seasons. Most of the time, I am the only GIS professional working at the county. I try to keep a GIS intern employed, but with semester changes and graduation, there is downtime. Before the recession, Fremont County GIS maintained a staff of four. Now, fiscally challenging times make regional collaboration all the more important.

Neighboring counties face many of the same challenges. Sharing data and collaborating on the development of regional datasets are part of any successful GIS work program. Few things can be more exasperating than completing a project only to find someone else has already done the work or found a better way to do it. Being part of a regional GIS allows face-to-face interaction and the development of friendly and helpful associations. Meetings can be designed so that everyone can gather at a local restaurant afterward. In the business world, many deals have been struck during a meal. When people are relaxed and enjoying themselves in a less formal setting, challenges are seen in a different light. Often, assistance is more freely offered, and personal friendships develop that improve working relationships.

Travel

Traveling long distance for meetings is also part of the work program. Just about anything that cannot get done over the phone or by e-mail requires traveling. Rural Idahoans are used to it; it is part of daily life. Still, EIRRC employs online conferencing to include those individuals who cannot always travel. This helps to keep everyone involved and the work moving forward. Personally, I look forward to face time and to interacting with other GIS professionals, even if it burns up much of a workday. In the long run, it improves productivity through insight into creating products that have a longer life cycle. Thornier issues, such as standards for core GIS datasets (i.e., parcels and roads), are more easily addressed through a little give and take around the table. And the ability to read nonverbal communication helps steer the topic in a helpful direction.

As a young professional, I dreaded meetings as unproductive downtime and useless bantering by people who seemed never to get anything done. Over the years, however, I found that such meetings were tools of collaboration that prevented problems and produced products useful to everyone. Now I look forward to opportunities that allow collaboration and professional relationships to flourish. Because Idaho provides such opportunities, the future looks bright for the state, the region, the organization, and the individual.